South Philadelphia dad and Little League coach Alex Kaslowitz remembers watching the Phillies play at Veterans Stadium, one of the first to install artificial turf in 1970. Since then, as reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer, six former Phillies have died from a rare form of brain cancer linked to the turf they played on.

“That really hit me hard because I can literally picture these players. I can picture the stadium and the heat — you would even see it was cloudy on the very hot days,” Kaslowitz said. “And you know, the catcher’s sucking in all this air … and then to hear that there was a correlation.”

It’s this history that informs Kaslowitz’s opinion that synthetic turf is not safe for kids to play on.

Since a 2019 report by The Ecology Center and Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility found that PFAS — aka “forever chemicals” — are pervasive in synthetic turf, parks departments, school districts and other land managers that oversee playing fields have faced tough choices about whether to continue to use the low-maintenance surfaces.

PFAS, which stands for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are synthetic chemicals useful for making materials slippery (Teflon is one example) and water resistant. Since the 1950s, thousands of PFAS have been used for a variety of purposes, including lubricating the machinery that produces the plastic blades of synthetic turf.

“Recently, there was discussion about PFAS as a carcinogen, and also a lot of research showing that PFAS could relate to high cholesterol levels and coronary heart disease, and also association with impaired fetal development,” says Dr. Aimin Chen, professor of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and co-director of the Philadelphia Regional Center for Children’s Environmental Health. “There are other [studied outcomes] like preeclampsia during pregnancy and potential associations with [chronic] liver disease.”

On artificial turf, kids can be exposed to PFAS via ingestion or inhalation of turf particles, especially if the turf is degraded. (The average lifespan of an artificial field is eight to 10 years). The exposure doesn’t end on the field; kids often track turf particles into homes after sports practice. And since the turf eventually has to be disposed of in landfills, according to Chen, PFAS chemicals can contaminate groundwater and soil.

Regulators have responded by setting restrictions on some PFAS. In February, the FDA announced a ban on PFAS-containing grease-proof food packaging. In April, the EPA established the first legally-binding national standard for drinking water in order to limit exposure to PFAS.

Some states and cities have enacted bans and regulations on synthetic turf. Last fall, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed into effect a law that allowed cities to ban synthetic turf. San Marino in Los Angeles County, Millbrae in Northern California and others have already begun the process.

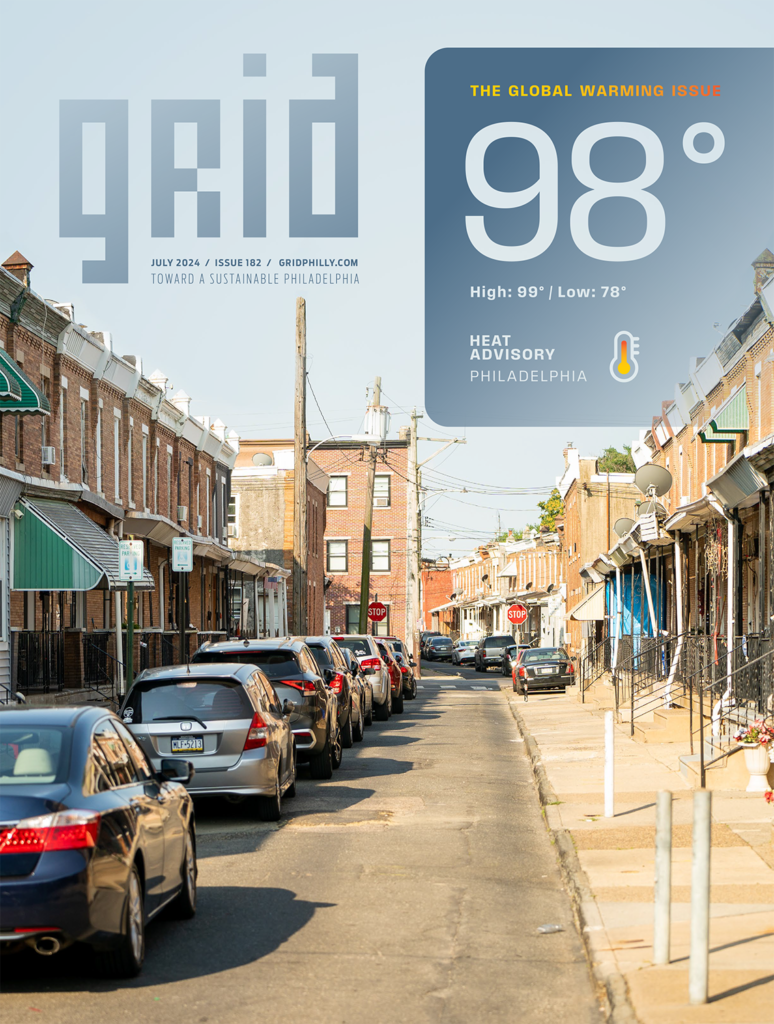

In Philadelphia, access to fields — particularly pristine green fields — has long been seen as an issue of class. While there is no shortage of fields in the suburbs, in the under-funded city of Philadelphia, high-quality fields are harder to find, which has led the park system to increasingly install synthetic turf fields.

The question of whether this is a safe choice has come to a head at FDR Park, the largest park in South Philly, that is on track to receive twelve synthetic turf fields as a part of its $250 million renovation overseen by the nonprofit Fairmount Park Conservancy.

The renovation officially started in 2022 and will take decades to fully complete. Currently the park is in the first part of its development process, which is set to be completed by 2026. Most contentiously, this stage includes the replacement of a defunct golf course, which became a cherished natural space known as “The Meadows” during the pandemic, with artificial turf playing fields.

“The new fields will help address the well-documented citywide field shortage, offering kids more places to play during more hours of the day, making it easier for kids to play closer to home, and reducing costs for families to travel,” the Fairmount Park Conservancy said in a statement to Grid. “Playing fields are essential for the youth of our city, providing mental and physical health benefits. Currently, in South Philadelphia, there is only one regulation-size turf field in the Philadelphia Parks & Recreation system for 21,000 kids living below South Street.”

It can overheat hot enough to kill a child … the intersection of climate change with the installation of these synthetic turf fields is like a death sentence for kids.”

— Anisa George, Save the Meadows

Community members opposing the clearing of the former golf course, some of whom formed an advocacy group called Save the Meadows, have concerns about the fields’ potential health impacts on youth athletes.

“It’s not a [natural] environment so it doesn’t photosynthesize, it doesn’t sequester carbon. It’s not a habitat for birds and worms, et cetera,” Anisa George, organizer with Save the Meadows, says. “It can overheat hot enough to kill a child … the intersection of climate change with the installation of these synthetic turf fields is like a death sentence for kids.” Studies have shown that synthetic turf can reach temperatures higher than 160 degrees Fahrenheit, which is more than 60 degrees hotter than grass fields.

The Fairmount Park Conservancy maintains that it is but a “popular misconception” that the FDR Park Plan includes “[AstroTurf] products containing PFAS.”

“Modern performance turf products use all-natural infill composed of materials … ensuring a safe playing experience that is also sensitive to the needs for climate resiliency. The Conservancy, the City of Philadelphia and partners are aware of the health concerns associated with turf products of the past and are fully committed to selecting and installing turf that is safe. The product selected will be independently tested and certified for safety,” the Conservancy’s statement says. The statement includes mention of modern, “all-natural” turf infill, made with materials such as walnut shells, sand, coconut fibers, or cork, but does not address the plastic grass blades, where PFAS is found.

“I’m trusting in the planners that they have done this,” said John Maher, president of the Philadelphia Dragons Sports Association, in reference to the City’s commitment to finding PFAS-free turf. “They have publicly committed to only putting that type of surface down, and they’re going to be held accountable to that. That’s why we as an organization see [PFAS concerns] as a non-issue.”

We underestimate what an eight-year-old or even a five-year-old understands. This isn’t just a battle with decision-making adults. These kids are fully aware of what’s happening.”

— Alex Kaslowitz, South Philly Little League Coach

However, activists have pointed out that PFAS-free turf simply does not exist. And in a letter to the state of California in light of a proposed PFAS regulation bill, the Synthetic Turf Council — which represents synthetic turf manufacturers — admitted that it would take until at least 2026 to remove PFAS from artificial turf products, writing: “We believe it would be more prudent (in addition to allowing for testing protocols to be developed) to establish the compliance threshold for unintentionally added PFAS at 110 ppm [parts-per-million] beginning in 2026 and 50 ppm in 2028.” The FDR Park Plan stage that includes artificial turf installation is slated to be complete by 2026.

Maher says that if it were up to him, he’d choose grass and dirt fields, but he recognizes that maintenance can be a problem. “The only way that the existing fields that we have at FDR get maintained is that we pay to do that ourselves,” he says. “When I weigh the considerations of the City making an enormous investment in fields that then potentially would not get maintained, versus putting in fields that are going to be the most feasible to maintain, I think that makes the most sense because it will enable us to have more sports programming available for the use of Philadelphia.”

There’s also the impact of weather. As the Conservancy wrote in their statement: “The performance turf of the new athletic fields will provide a reliable playing surface that is able to accommodate multiple games per day and rebound almost immediately from flooding and rainstorms.”

In addition to the Fairmount Park Conservancy, Grid reached out to better-resourced entities that manage synthetic turf fields. The University of Pennsylvania (which currently hosts two artificial turf fields), Springside Chestnut Hill Academy (a private K-12 school in Philadelphia), and the Haddonfield School District in New Jersey did not respond. The Lower Merion School District declined comment.

Kaslowitz says that even his children — eight-year-old Leo and five-year-old Coen — see the implications of synthetic turf fields for the surrounding environments.

“We underestimate what an eight-year-old or even a five-year-old understands,” Kaslowitz says. “This isn’t just a battle with decision-making adults. These kids are fully aware of what’s happening.”

Sorry to say, but the kids do not actually fully understand that their health may be at risk, so to state that they do is completely bogus. In my town, the coaches and sports crazed parents go on and on about the need for extended playability and maintain that turf is the only answer but it has been proven that this is not true. Many towns have implemented clever solutions and work to ensure that organic grass fields are maintained and rotated. All kids hear is what they are hearing on the ball field and at home with their parents, who are not discussing the possible health ramifications of how toxic the turf is to inhale, bringing home shredded plastic grass blades in their underwear and sox, playing on a hotter than heck heat island over over 160 degress and that is just for starters. Do the parents explain to these kids that there are other internal health risks. After all, kids look healthy and so it must not be a concern….until it is. Then what? Was the extended hours of play really worth it? Parents is most instances have not researched PFAS or that turf needs to constantly be sanitized from bodily fluids of sweat, spit and blood just to name a few. What about those chemicals rubbing up against and abrasion on that hard plastic grass? There is more and more data coming out every day and just like cigarette smoking, exposure to lead or asbestos, what we know now is important and what we didn’t know, well, it is what it is. Why not be smart with our children’s health. We don’t need turf companies who make millions telling us it is safe, when we know that isn’t true and it is also bad for our climate and is not being recycled. We need independent testing and unbiased reports to provide real data. Lets tell these kids that PFAS sad PFOS are toxic with a very limited abillity to be biodegradable, they are persistent in the environment,

and pose a significant risk to human health and safety. PFOA and PFOS are associated with a variety of illnesses, including cancer, and considered particularly dangerous to pregnant women and young children. Then tell them about the climate that it will ruin, you know for their future and the future of their kids. Let’s also tell them that the turf companies say it is safe, although some of them are in class action suits, but it is ok because they make millions from cities and towns all over the US and hiring a top notch lawyer to defent potential litigation is no biggie. Let’s way all of the options. Then I would like to see what these informed kids and parents have to say.