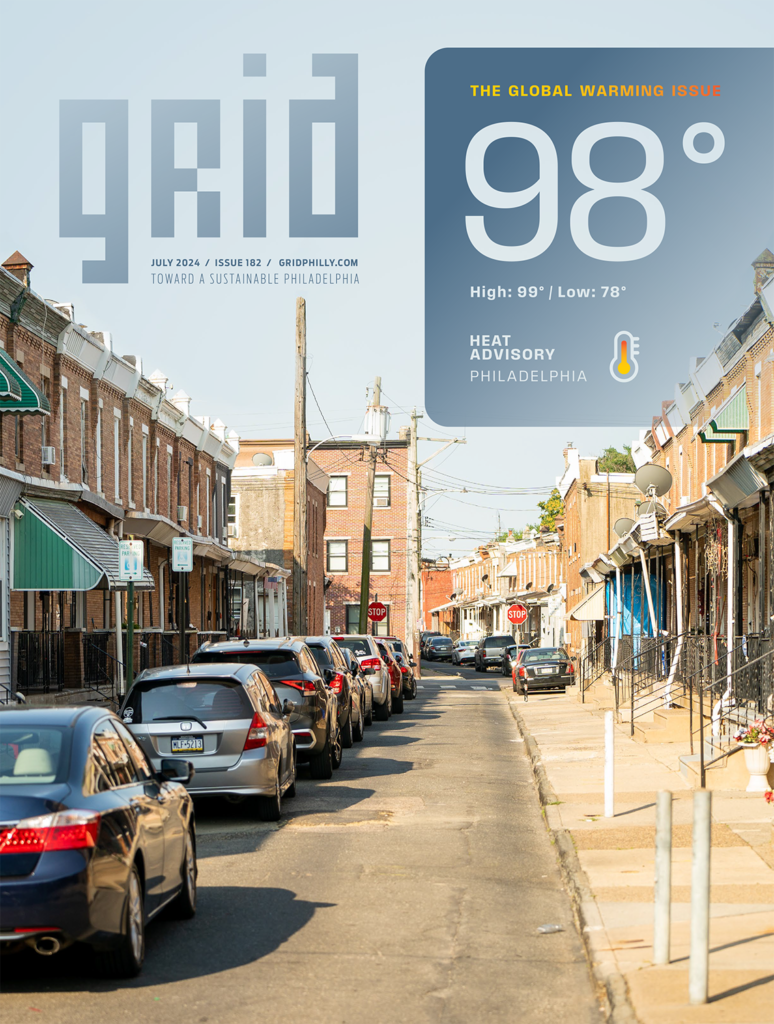

When the U.S. Department of Agriculture released an updated map of hardiness zones last November, gardeners and farmers in the Philadelphia region — and across much of the United States — found affirmation of the warmer weather they’ve been experiencing since the map’s last refresh in 2012. In just over 10 years, nearly half the country shifted into a new zone, meaning new plants can survive through increasingly mild winters while others are now a better fit farther north.

In 1990, Philadelphia was split between zones 6b and 7a, but now nearly all of it is entrenched in zone 7b, indicating a 10-degree rise in the coldest winter temperatures over the last four decades. As the effects of climate change accelerate in the coming years, the zones will continue to shift. The Philadelphia Orchard Project (POP) isn’t waiting to see what that could mean for our diet of local produce.

In two unheated high tunnel greenhouses that opened this spring in The Woodlands in West Philadelphia, POP plans to experiment with the foods of our future. Under shelter from winter’s harshest conditions, the nonprofit hopes to learn about which trees might bear fruit a decade or two from now that might once have been reserved for warmer locales, including Chilean and pineapple guava, pomegranate, Orinoco bananas and hardy citrus like kumquats and yuzu.

This is a way to expand that knowledge, share it with partners and eventually expand their food production.”

— Phil Forsyth, Philadelphia Orchard Project

“The primary service we provide the city of Philadelphia is knowledge about fruit growing,” POP co-executive director Phil Forsyth says. “This is a way to expand that knowledge, share it with partners and eventually expand their food production — with more culturally relevant plants, in many cases, because we’re able to push into parts of subtropics where many Philadelphia immigrants and other communities come from.”

In early May, the high tunnels were full of early spring’s anticipation, rather than the fruit Forsyth hopes to see emerge in time. A banana tree had been put in the ground just a week earlier; he’s confident it will survive this winter and hopeful it will fruit next year. One of the 48-by-22 foot greenhouses is intended as a nursery and workshop space and the other will house POP’s subtropical experiments. In addition to fruits foreign to the Philadelphia region, POP is planting more familiar fruits, including raspberries, strawberries, blueberries and a fig tree, to learn whether the high tunnels can help extend the harvest season.

“It’s a process of experimentation and seeing what works,” Forsyth says. “We’re not relying on our orchard to provide our living. We’re doing this for a variety of purposes — educational value being one of the highest, as well as ecological value and engagement. So if every experiment isn’t a success, it’s still worth doing.”

The two structures cost more than $100,000 to build, Forsyth says, a significant portion of which went toward permitting because of the Woodlands’ status as a historic site. It would cost much less to build elsewhere and POP wants to show other growers what a high tunnel can accomplish. Dozens of high tunnels already exist in the city, Forsyth says, but they’re used primarily for growing vegetables. “Nobody’s been thinking about fruit production,” he says.

Forsyth is already thinking ahead to POP’s next big investment, a climate battery greenhouse that would occupy more space than the two high tunnels combined. The greenhouse would utilize the earth beneath the structure as a thermal battery of sorts to stabilize its temperature and humidity, using buried tubing to transfer heat between the ground and air. His inspiration for that project comes from Threefold Farm in Mechanicsburg, Cumberland County, where Tim Clymer has been using the setup since 2017 to graduate from zone 6b to 8a so he can grow fruits native to the Texas climate where he and his wife used to live.

After using a citrus tree as a “canary in the coal mine” during his first winter with the climate battery, Clymer has watched figs flourish without any dieback ever since. He’s grown satsuma mandarin, Meyer lemon and avocado, and last winter he pushed the envelope even further with star fruit, lychee, longan and mango. He’s not sure whether it will all prosper — the jackfruit didn’t survive — but he’s found a market for fruits uncommon in this region. He sees great value in growing in-demand fruits that don’t need to be trucked or flown in from thousands of miles away.

“Sometimes it takes someone like the Philadelphia Orchard Project to showcase something like this and say, ‘It actually can be done,’” Clymer says of the nonprofit’s plan to expand from high tunnels to a climate battery in the coming years. “It’s different to see it versus just hearing about somebody somewhere who has a magical greenhouse that can grow South Florida plants. If we can get more and more of them, it raises awareness that there are alternatives to strapping a propane heater on and burning a lot of fossil fuels [to grow plants].”

Whether in a high tunnel or a climate battery greenhouse, adapting to the hardiness zones as they creep northward will require research and forethought, according to Kathy Demchak, senior extension associate at Penn State University’s College of Agricultural Sciences, whose work focuses on berries. Penn State has been experimenting with high tunnels since the early 2000s, she says, doubling the harvest season for some fruits and offering a way to grow crops like sweet potato and luffa (aka loofah) that wouldn’t typically be found in Central Pennsylvania.

“I always looked at the high tunnels as a way of predicting what the future climate could look like,” Demchak says.

Any experiment is bound to encounter failure somewhere along the way, but POP’s foray into far-flung fruits is bound to reveal something meaningful about what growers will face in Philadelphia’s future. “Something’s going to work,” Demchak says. “It may not be what you think it will be, but something will work, so I think there’s a lot of potential in what they’re trying out.”