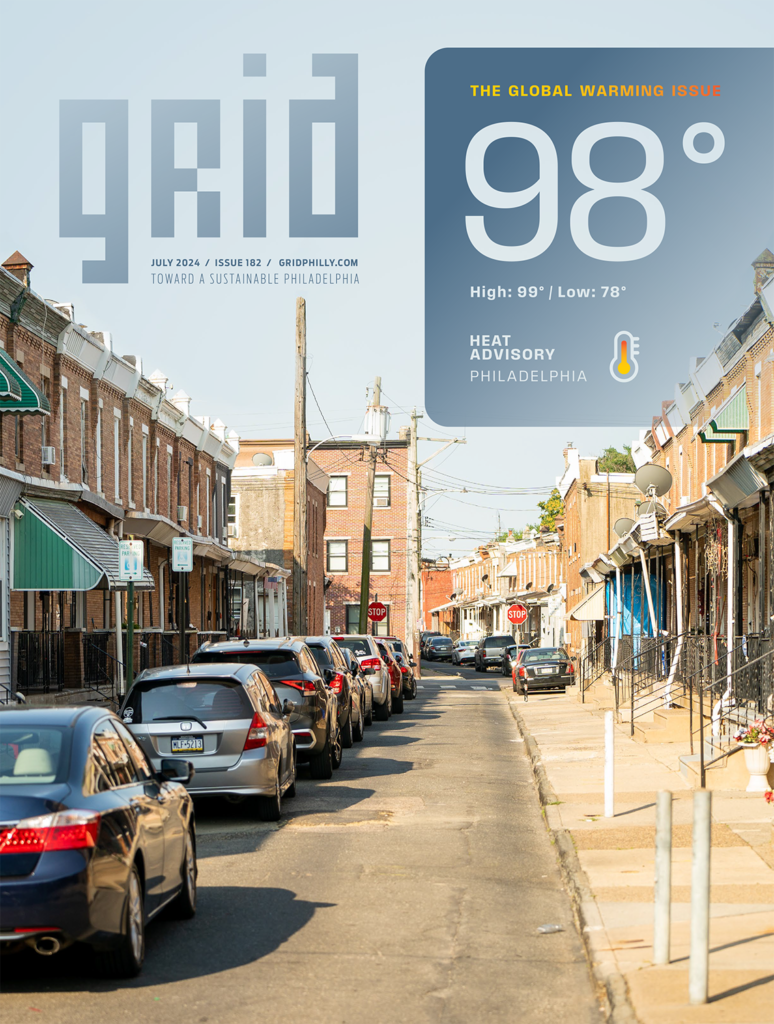

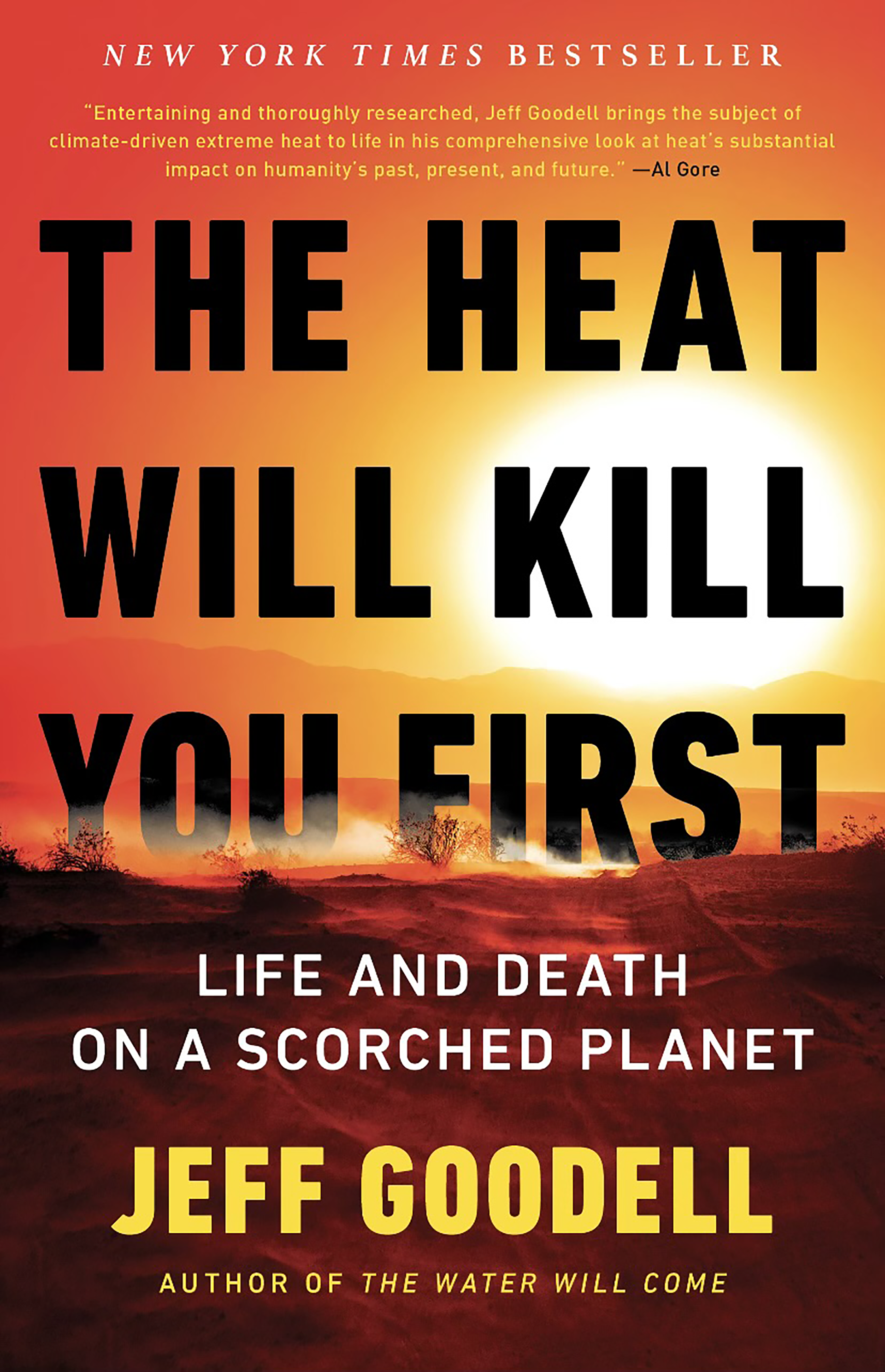

The title of Austin, Texas-based journalist Jeff Goodell’s 2023 book, “The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet,” should leave no doubt as to the topic and its urgency. Grid spoke with Goodell at the end of May about the most lethal and least visible natural disaster on the planet.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why the heat first, not the wildfires or hurricanes? I happened to be in Phoenix on a summer day in the summer of 2018. The temperature was 115 that day. I had a meeting downtown. As usual, I was late. And as usual, my Uber was late. So I decided I was going to run 20 blocks through downtown Phoenix on a hot summer day. Not a good idea. By the time I got through those 20 blocks, my heart was pounding and I realized that if I pushed it any harder, I could be in big trouble.

It was at that moment that I really understood how dangerous heat is. It’s not just some sort of abstract thing in the distance. I wanted the book to have the same effect for the reader that that 20-block run did on me that day in Phoenix.

We’re used to talking about averages when we think of climate change, but they mask the extremes, which are what really kills you. How should we be talking about heat? Top scientists in the world set these targets of two [degrees] Celsius of warming, 1.5 Celsius of warming. First of all, the Celsius thing means nothing to most Americans. But even if you translate [2 degrees Celsius] into Fahrenheit, which is 3.7 degrees, it still sounds like nothing.

You tell someone, “Oh, instead of being 68 degrees today, it’s going to be 71.7.” Yeah, big deal. I’m not surprised that most people don’t think about it or care about it, because it doesn’t sound very alarming at all.

But we had more than 40 days in Austin, Texas, last summer over 105 degrees. It was brutal. And yes, Texas is always hot, but we’re getting more and more heat earlier and earlier in the year. The heat waves are becoming more intense. There’s less cooling off at night.

There’s an accumulated impact on these long days as buildings heat up, pavement heats up, and it radiates more and more heat back. So a one- or two-degree change doesn’t really capture what’s happening. The perfect example of that was the extreme heat wave in the Pacific Northwest in 2023.

You write about how we are good at ignoring deaths, particularly when they are of “other” people. Could you talk about who dies in heat waves, and how that affects how urgently we treat it as a problem. In the book, I call heat a “predatory force” in the sense that it goes after the most vulnerable people first. And vulnerability can be defined by age, by health conditions. Pregnant women are more vulnerable; if you’re on certain kinds of drugs that change your metabolism and your reaction to heat, that can make you more vulnerable; outdoor workers and people who don’t have access to air conditioning [are more vulnerable]. There are 760 million people on the planet who don’t have access to electricity, much less air conditioning.

So I think a lot of people who are reading this, they think, “Well, what’s the problem? You turn on the air conditioner and you will be fine.” We’re not going to be fine, because a lot of people don’t have air conditioning. Also, we’re not going to air condition the oceans. We’re not going to air condition the forests. We’re not going to air condition the crops that we depend on to feed ourselves. So the implications of these extreme heat events go far beyond our temporarily cooled little bubbles.

There are a lot of scary facts in this book, but one of the scariest to me was that modern, well-sealed, energy-efficient buildings lose their ventilation systems when the power goes out. Air conditioning has had a big impact on the demographics of America. Florida would not be Florida. Austin, Texas, would not be Austin, Texas, without air conditioning, right? But the problem is, first of all, a lot of people don’t have access to it and for all intents and purposes won’t have access to it.

Second of all, as you just suggested, it’s a kind of delusional bubble that can go away very quickly with a blackout. Here in Texas, we had a five-day blackout in the winter a couple of years ago. Houston just last week had a big windstorm that knocked out power for a million households for three days.

Luckily, the temperatures weren’t so high.

A lot of studies show that a major blackout combined with a big heat wave would have enormous casualties. One study that I cited in the book suggests that with a five-day heat wave combined with a two-day blackout and a three-day gradual restoration of power in Phoenix, half the city — 800,000 people — would end up needing emergency care and about 13,000 people would die.

People lived in Texas before there was air conditioning. And they built in a very different way. They had transoms that opened above the doors. They oriented their houses away from the direct sunlight, they planted big trees for shade. They had what are called ‘dog trot houses,’ where they had a big central corridor with main living quarters on either side, so there would be a strong breeze coming through.

Even in Philadelphia, sleeping porches used to be a common feature of houses. Yeah, exactly. And so we’ve given that all up now.

Even when we get to the magical net-zero emissions of carbon, which is decades away at best, even that will only stop the increase in temperature. It will not take us back.”

— Jeff Goodell

So many of our older cities weren’t built with heat in mind. Aside from the obvious cutting greenhouse gas emissions, what can we do to make cities survivable as the planet warms? It’s really important to underscore that this risk of heat is driven by the consumption of fossil fuels. It’s also really important to make clear that even when we get to the magical net-zero emissions of carbon, which is decades away at best, even that will only stop the increase in temperature. It will not take us back.

The obvious thing that many cities are doing — because it’s the easiest and the most politically palatable — is planting more trees. That’s really important. There’s lots of studies that have shown that street trees do a lot to cool off a city. But trees aren’t magical solutions, they require care and maintenance.

Changing the infrastructure is really important. It’s going to take some time, though. One city that’s leading the way is Paris, and they’re doing it because they have a mayor who is probably one of the most climate-savvy politicians in the world. They’re narrowing the big boulevards, putting in more trees and greenery. They are restricting automobiles and vehicles with internal combustion engines from the downtown, cleaning up the Seine so that you can swim in it on many days. They’ve done a lot to change the heat anatomy of that city.

When it’s a hot day, you need to be paying attention so that you can target your response during heat waves to these particularly vulnerable people. And that’s a big deal, just understanding where the vulnerability is.

The other point that I underscore is that we’re at this turning point with climate and heat and thinking about this, and I think it really is opening up a lot of opportunities for building a better world. The question is, do we do it in an intelligent way? Do we get educated about it and make smart choices or do we just do the “Mad Max” scenario?