Nature enthusiasts often speak of a “spark species” that inspired their love of nature; it’s hard to think of one more popular than the monarch butterfly, which captivates thousands across North America with its flashy colors and extraordinary annual migration.

These iconic butterflies hold a name brand recognition not given to most insects. We see them fluttering about Philadelphia and guest starring in exhibits at the Academy of Natural Sciences and Tyler Arboretum. Their migration is studied at NJ Audubon’s nearby Cape May Bird Observatory, where people can enjoy their beauty and even participate in data collection.

All this attention on monarchs can be traced back in part to 1990, when Mexican officials released data showing a decline in overwintering populations that was believed to indicate a significant decline in the whole monarch population. This spurred an entire movement to “Save the Monarchs,” prompting articles, conservation efforts and funding. The monarch became an icon of conservation far surpassing any other insect.

But as scientists dig into the data, a question has arisen: do monarchs actually need saving?

This year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will decide whether or not to list monarchs as an endangered species, but many scientists are saying the data don’t support the narrative of decline. Findings show that the overall population of monarchs remains steady — despite changing migration patterns and the spread of a debilitating parasite, which some scientists say are causes for concern. For weighing less than one gram, these beautiful butterflies have sparked a ton of controversy.

The complex life cycles of monarchs may explain some of the confusion in understanding their abundance. Each year provides four generations of monarchs, each going through four life stages. In the springtime, a female monarch lays 100-300 eggs on milkweed, which is also their favorite food source. These eggs hatch into baby caterpillars that spend their time munching the milkweed until it’s time to pupate or transform into a chrysalis. As the chrysalis hangs from a stem or leaf via silk threads, the metamorphosis occurs until the vibrant monarch butterfly emerges after eight to 15 days.

That “first generation” butterfly will live about two to six weeks and die after laying eggs for the second generation, which will do the same thing into the third generation. Each generation moves a little bit further north until the fourth generation changes the game plan. This generation, typically born in September and October, goes into reproductive diapause, meaning they hit pause on mating and laying eggs. Instead, they fly up to 3,000 miles south to spend the winter in central Mexico where they cluster on oyamel fir trees in spectacularly large groups. In early spring, the butterflies begin their journey north to start the cycle all over again. The fourth generation can live up to nine months to facilitate this process.

There’s an amazing amount of attrition during that fall migration — some natural, some anthropogenic, but it is massively underestimated.”

— Andy Davis, University of Georgia

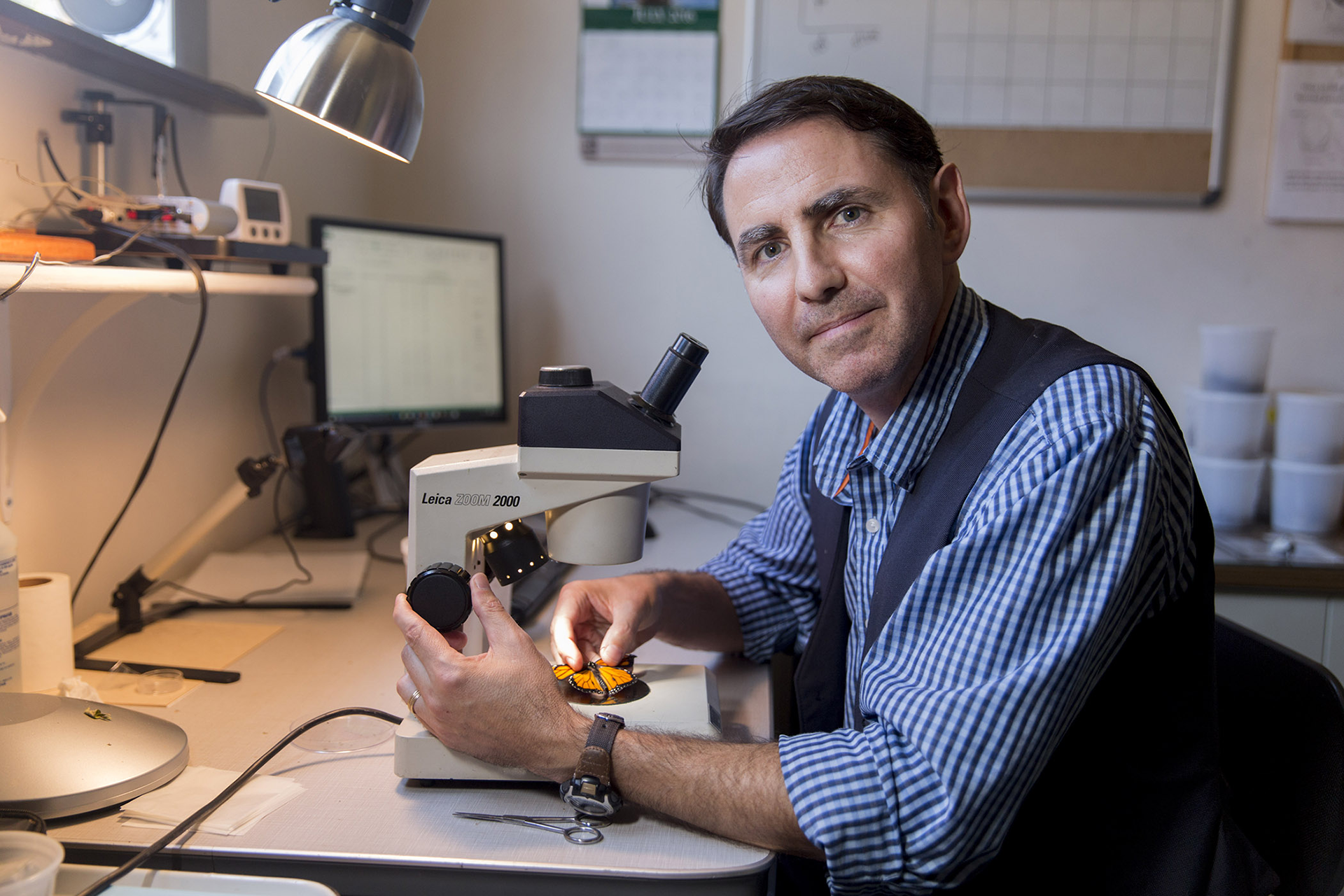

So how do scientists determine the population of monarchs when their lives are so complex? Because monarchs cluster while they overwinter, traditionally many scientists studied these populations and inferred that the overwintering population should reflect the overall population. But Andy Davis, a research scientist from the University of Georgia, says this operates on the assumption that the entire monarch population makes it to Mexico.

“It’s as if all the monarchs just jump on a bus and it arrives in Mexico and lets them out and they all hang out in the trees so they can be studied, the entire population,” he says. “But it’s probably never been that. There’s an amazing amount of attrition during that fall migration — some natural, some anthropogenic, but it is massively underestimated.”

If scientists look at only the overwintering population after the population die-off that occurs during migration, they miss the incredible resilience and quick bounce-back occurring during the breeding season. As climate and land uses change, so does the variability of when and where the monarchs will be most and least robust in their population, and that needs to be accounted for, Davis says.

While some data sets show decline in the overwintering population in Mexico, Davis and his team used extensive data spanning 1993 to 2018 from across the entire geographic range of monarchs to model the population. Their advanced statistical analysis showed that the population remains “bouncy” with no real decline. Davis says the data pronouncing the decline of monarchs isn’t wrong, but “it’s just one snapshot of one time point in a very complex life history.”

Another study by Josh Puzey, a plant biologist and genetic scientist at The College of William & Mary who studies monarchs and milkweeds, says something similar: the genetic diversity of monarchs has not significantly decreased. The census population — what most people mean when they say population — refers to the actual number of individuals within a population, whereas the genetic population reflects the diversity among individuals of a species. The genetic population can be a pretty good indicator of whether or not a species has experienced a “bottleneck,” or a significant population size reduction that in turn limits genetic diversity. Because the genetic diversity of monarchs has not significantly decreased, Puzey and his team of scientists, including monarch expert Anurag Agarwal, infer that it is unlikely their census population has experienced a significant decline either.

“If any decline is occurring, it is a natural contraction,” says Puzey. He reflects on the “snapshot” that Davis referred to, versus the longer time scales found in natural cycles and how our perspective of the monarch populations can be colored by this complexity. “As humans, our time span is limited in how we observe these occurrences.”

He also points out that the monarch population that scientists have observed for the last 200 years may have experienced a human-caused expansion. He refers to work by Lincoln Brower and the idea that when Europeans came to the eastern United States, it was heavily forested without open fields and large populations of milkweed. There are no mentions of monarch butterflies by naturalists until 1857, as the westward expansion was underway and Europeans became more familiar with the great plains and open areas of the Midwest. Europeans cleared great swaths of forests in their colonization and in doing so created monarch habitat that led to an increase in population.

Puzey wonders, what is the baseline? “This is where we get into conservation philosophy. Are we trying to conserve current populations, or trying to get to historic levels? It’s not as simple of a story as we make it out to be, there are many layers.”

Adding to the complexity, some widely adopted monarch conservation strategies are actually proving to be detrimental. As is the case with many things in nature, people may now be loving monarchs to death.

Many conservation groups encourage people to raise monarchs indoors and then release them, which sounds great in theory. But concentrated populations of monarchs raised indoors in close proximity are more likely to contract and spread a debilitating parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE). Effects of the parasite can range from shorter life spans and difficulty flying to the inability to develop properly and emerge from the chrysalis. Beyond the OE calamity, studies suggest that the captive reared monarchs don’t fly as well as wild monarchs to begin with. Davis worries about these poor flying genetics mixing with wild genetics and contributing further to the migration attrition.

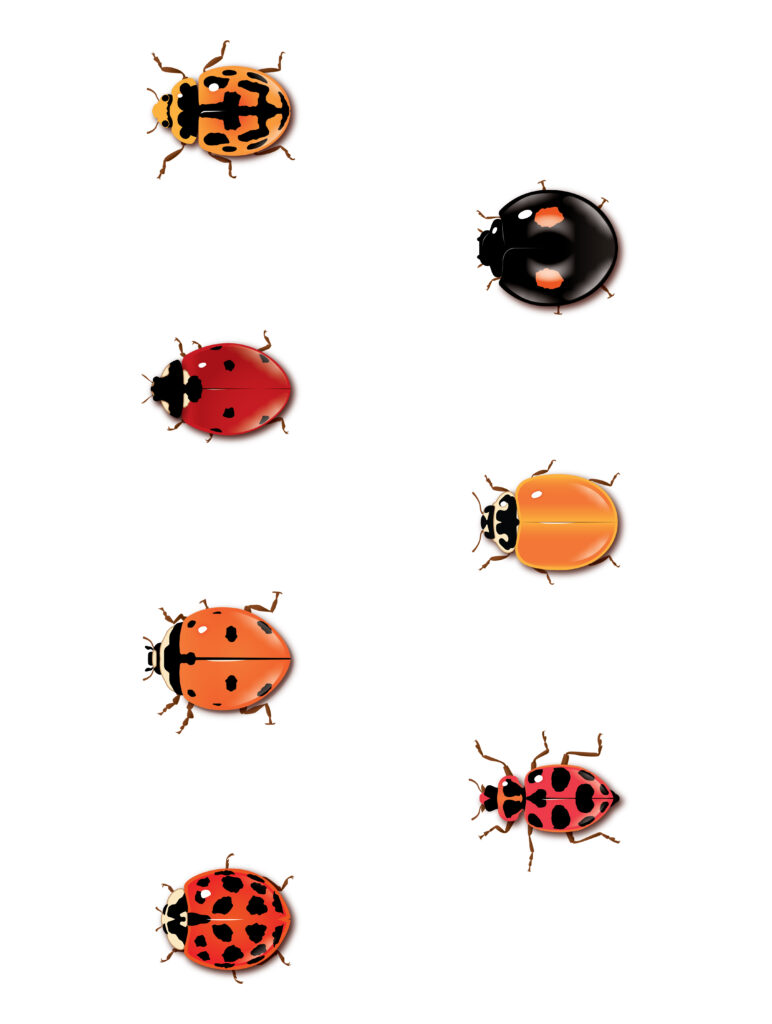

Another issue is the planting of non-native milkweeds. Good-hearted folks hear that they’re supposed to plant milkweed for monarchs and go running to their nearest store where more often than not, the only available milkweed is tropical milkweed. (The three species most common to the Philadelphia region are common milkweed, butterfly weed and swamp milkweed.) Tropical milkweed can provide food and shelter to monarchs, but it is not in sync with local seasons and blooming periods. It can bloom throughout fall and winter and trick monarchs into stopping their migration or breeding outside of the appropriate season when they are not likely to survive due to cold weather. Tropical milkweed also plays a role in perpetuating the spread of the OE parasite.

Davis worries that the spread of misinformation around monarchs and the efforts to save them may be what actually leads to their decline. What he calls people’s “emotional affair with monarchs” seems to be superseding the scientific evidence telling us a more complete story about monarch populations and how to actually support their health and biodiversity in general.

Davis suggests that if people really want to help monarchs and all insects, and in turn the entire food chain, they should take a section of their lawn and re-wild it — stop mowing and let the grass grow tall, or put in native plants or wildflowers. Mount Moriah Cemetery horticulturalist Joanna Cosgrove says that it’s a challenge to get gardeners to plant native milkweeds because they aren’t as showy as the tropical varieties and can take over a space. But, she says, practices like removing the seed pods before they disperse can keep them in check.

Anecdotally, in her years stewarding Mount Moriah, Cosgrove has seen very few monarch caterpillars or eggs on the milkweed she tends. But quantitative data from local studies at Cape May Bird Observatory and from veteran citizen scientist Gayle Steffy, who studied monarchs around southern Pennsylvania for 18 years, show that monarchs continue to thrive here as well. The observatory’s Monarch Monitoring Project Annual Report 2023 states: “Wind and weather, alongside several other factors, can lead to varying monarch numbers in Cape May from year to year. Despite fluctuations in monarch numbers in Cape May, the average number of monarchs appears to be consistent over the past 30 years.”

To observe monarchs in migration locally, Adehl Schwaderer, the Monarch Monitoring Project program coordinator for NJ Audubon’s Cape May Bird Observatory, recommends that visitors come in September and October on a day with northwest winds. She takes a different view than Davis on popular conservation efforts. “There’s a delicate balance to being an outdoor educator. You have to meet the public where they’re at and not give them absolutes or scare them away,” she says. They do captive rearing at the observatory for educational purposes, but Schwaderer recognizes that there needs to be caution in how this is presented to the public. Everyone can agree that the story is not one dimensional.

While the current stability of monarchs provides good news, a larger “insect apocalypse” plays out in the background. Monarchs can continue to be the “spokesbug” for the beauty, complexity and importance of insects — but with the understanding of their relative abundance and health. One hope is that interest in their conservation may shift to populations in more dire need. Most simply however, scientists just want the data to be accepted without any embellishment or agenda.