It’s 7:30 a.m. on a Friday in late March and Stephen Maciejewski is walking around Center City looking for dead or injured birds.

He isn’t hoping to find any. But it’s spring migration, a time when millions of birds pass through the city on their way north. Maciejewski knows many of them are bound to strike the countless glass windows in Philadelphia’s urban core.

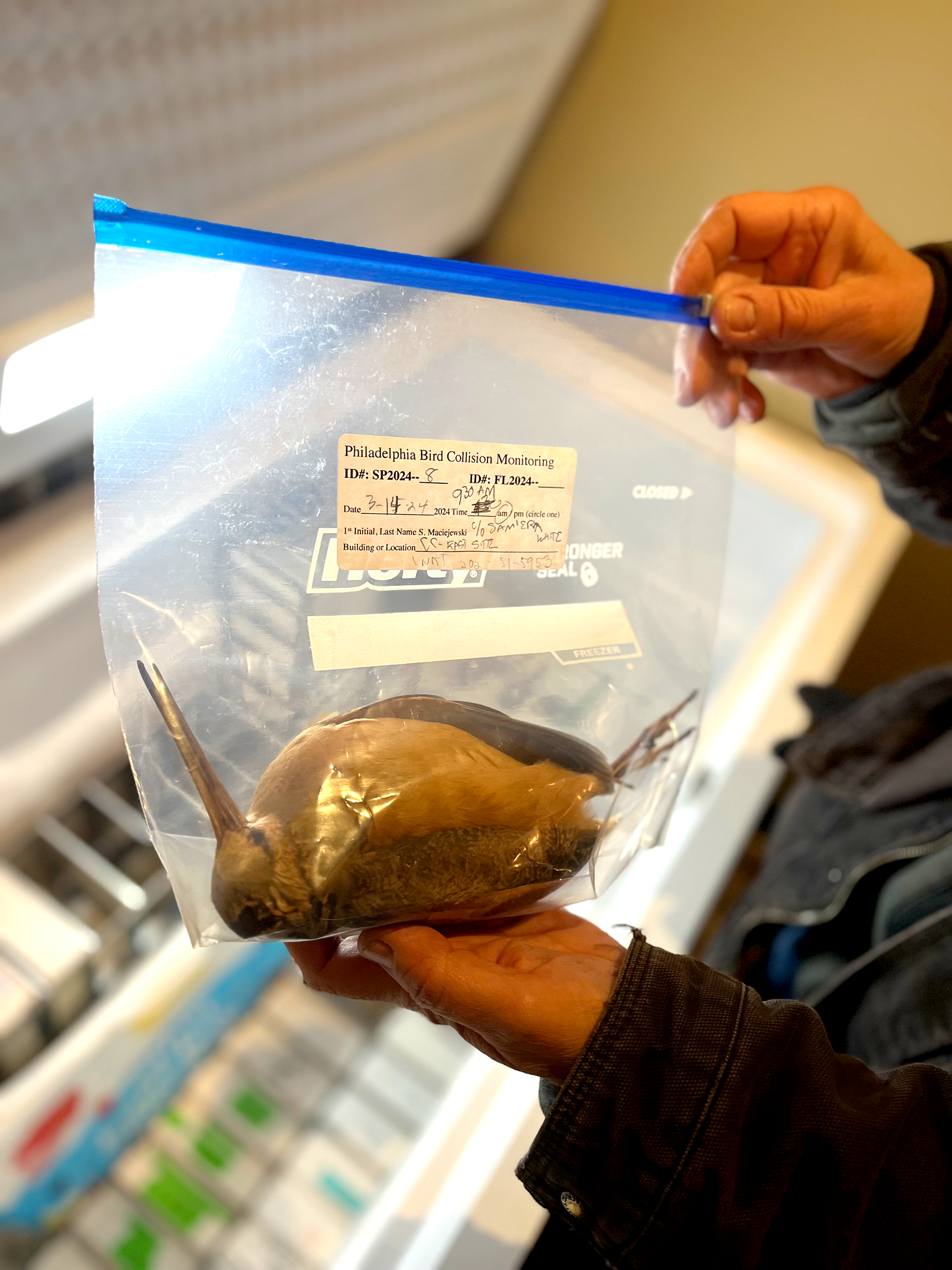

When that happens, Maciejewski, a volunteer with Bird Safe Philly, intends to document it. Over the course of his two and a half hour shift, which he begins daily at 5:30 a.m., he checks the perimeters of 18 buildings in the area. If he discovers an injured bird along his route, he takes it to a wooden box in a nearby building’s loading dock, where it will rest until another volunteer can drive it to a wildlife clinic for rehabilitation. If he discovers a dead bird, he places it in a bag, and eventually brings it to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, where it will be used for research.

Either way, he takes meticulous notes on his finds, recording the impacted species, the time of the collision and the building where it occurred, among other details. In just one four square block area in Philly, 1,000 such collisions happen every year, according to Bird Safe Philly’s data. And across the U.S., as many as one billion collisions occur annually. It’s the third biggest threat facing birds, after habitat loss and outdoor cats.

For birds, glass equals death. It’s just a matter of time before they’re gonna kill themselves flying into glass.”

— Stephen Maciejewski, Bird Safe Philly

Those collisions, Maciejewski knows, aren’t inevitable. Preventing them is the mission of Bird Safe Philly — a partnership of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Audubon Mid-Atlantic, Delaware Valley Ornithological Club, National Audubon Society, Valley Forge Audubon Society and Wyncote Audubon Society. The organization formed in 2020 after a mass collision event in which thousands of migratory birds died after hitting buildings in Center City. Maciejewski was walking the streets that day and documented the destruction. Better data on the frequency and location of such bird collisions, he hopes, can inform interventions to stop them in the future.

“For birds, glass equals death. It’s just a matter of time before they’re gonna kill themselves flying into glass,” he says. “A lot of people kind of ignore it, but you really can’t ignore it when you see it every day.”

In the years since its formation, Bird Safe Philly has been busy. The team started Lights Out Philly, an initiative that enlists property managers to voluntarily turn off or block as many external and internal building lights as possible at night during spring and fall migration. Turning off lights protects birds from nighttime collisions, potentially reducing deaths up to 80%. Today, more than 100 buildings are participating in the program.

“We didn’t realize the impact that we were having and [Bird Safe Philly] opened our eyes to it,” says Rich McClure, a member of Building Owners and Managers Association of Philadelphia (BOMA), a commercial real estate organization that has partnered with Bird Safe Philly on the Lights Out Philly program. “And it was an easy lift.”

Organizers with Bird Safe Philly are still working to get more buildings on board with Lights Out Philly. But they know that even if all the buildings in the city went completely dark at night, the problem wouldn’t be entirely solved. That’s because birds can also hit buildings during the day.

“Artificial light at night is still a big problem, but the glass is a bigger problem,” says Keith Russell of Audubon Mid-Atlantic. “It’s proliferated to the point where every new building is full of glass, and the glass has been perfected since the ’60s to be extremely even and flat. Because it’s now so perfect, it creates perfect reflections, and that makes it much more susceptible to birds flying into it.”

To prevent those collisions, property managers can apply dense patterns to windows, cover them with paint or vinyl, or hang screens on them. And with Bird Safe Philly’s help, some buildings have been adopting some of those methods. At Springside Chestnut Hill Academy, the organization helped third graders apply adhesive markers and bird decals to the cafeteria windows, and helped the Briar Bush Nature Center in Abington, Montgomery County, and the Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust apply the same solution to several buildings situated in a wooded preserve. In 2023, along with Center City District, the Bird Safe team helped Sister Cities Café — a building enclosed by glass on three sides that faces tree-filled Logan Square — cover its walls with small dots, which they say drastically reduced the number of collisions.

There’s more action on the way. Andrew McDougall, a spokesperson for the National Park Service, told Grid that the agency will install “a bird-friendly film or etching” on the south end of the Liberty Bell Center sometime this year and will redirect the building’s outdoor lights downward instead of upward in an effort to reduce bird collisions. “We would eventually hope to do the same for the Independence Visitor Center. The National Constitution Center, I think we have to take a little more look at,” he says.

Generally, convincing organizations with an explicitly environmental focus (like nature centers) to retrofit their windows is not a tough sell. It’s more difficult when it comes to those that don’t share that mission. Turning off the lights at night can save property managers hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, but retrofitting windows comes with a price tag — one that Bird Safe Philly has found many are slow or unwilling to accept.

Take the Ciocca Subaru dealership in Grays Ferry, a building whose tall glass windows reflect the adjacent Stinger Park, had at least 79 collisions in the fall, more than any other building Bird Safe Philly monitored. It has not yet intervened to prevent bird collisions, despite multiple meetings with Bird Safe Philly. (Ciocca Subaru did not return a request for comment.) The Philadelphia Art Museum, whose glass-walled sculpture garden has been the site of numerous bird collisions, has “considered installing measures to deter birds from flying into the glass, but has not yet decided to install,” according to a spokesperson.

“[Window retrofits] are a cost, and they’re a complete look difference,” says Don Haas, a member of BOMA Philadelphia. “Especially if you’re on the first floor, a lot of times it’s retail. And if it’s retail… you don’t want to be blocking the optics.”

In cities and states across the country, legislation is superseding those aesthetic and economic concerns, making bird-safe design and practices mandatory for some buildings. The Maryland Sustainable Buildings Act, for instance, requires all newly-built, acquired or renovated state-owned buildings using state funds to use bird-friendly windows and lighting. In New York City, a law forces City-owned buildings to turn off the lights at night during migration season.

Stephanie Egger, a member of Bird Safe Philly, says similar legislation at the city or state level here is needed, but making it possible is an uphill battle. It would be especially difficult to force the change for privately-owned buildings; even Haas, a Bird Safe Philly partner, told Grid that he’s opposed to legislation that would require buildings to make accommodations for birds.

“[Legislation] would be a huge effort and we’re really far away from being able to make existing building owners do anything,” says Egger. “This is where relationship building comes in and working cooperatively with building owners and just trying to convince them that this is the right thing to do.”

At the end of his shift, Maciejewski heads to the Academy of Natural Sciences where he opens a chest freezer holding plastic bags filled with dead birds. In one bag, there’s an American woodcock, found dead on the east side of the 58-story glass Comcast Center on March 14. In another, there’s a brown creeper, found dead on March 15 on the building’s south side. “I’m like the avian undertaker,” he says.

For a bird lover like Maciejewski, it’s upsetting, finding “these really beautiful, intricately-colored birds dead again and again and again.” It’s more upsetting, still, for him to think about how many birds in cities around the world are meeting the same grim end. “The problem is not just in Philadelphia. It’s a monumental, universal problem. It’s hard to wrap your brain around it. We have to cut down on glass, but we’re addicted to it,” he says.

It’s a sobering thought, but it’s not enough to stop Maciejewski from hitting the streets again tomorrow, rain or shine. After all, he knows, there are still some birds that can be saved. “You have to go out there and keep on trying.”

As a member of this group, I share Stephen’s passion for helping wild birds survive their annual migration, and frustration with building owners who choose to see only the bottom line. I’d like to add that Comcast and the WHYY building are also big offenders. The WHYY is surprising because they position themselves publicly as a community oriented organization, but apparently that doesn’t apply to non-human residents of Philly. I encourage anyone reading this to contact Ciocca, Comcast, and WHYY to request they re-frame their thinking about this issue.

Terrific job with this article about our declining population of birds! Since 1970, the Lower 48 has lost 3 billion!!! If more environmental changes are not made–with glass and cats and habitat…. Generations to come will see many fewer birds!!!