By Noah Raven and Francis Raven

We filled our backpacks with over a dozen trees: chestnut oaks, black cherries and red mulberries, as well as two shovels, a pair of clippers, two pairs of gloves and several wooden stakes to label each of the seedlings. Our goal was to plant them in a degraded area full of invasive weeds where extra trees would help restore the native ecosystem and provide a local solution to the global biodiversity crisis. We hiked through a bramble of thorny multiflora rose bushes, ivy and other unknown invasives, trudged up a steep clay slope opposite a busy intersection and planted trees wherever there was a level opening.

This was our fifth time planting trees for our family project, Oakify Philadelphia. We’re guerilla gardeners. We’re not part of a larger organization and we plant without direct permission. To say we founded something may be too generous, but our project has a name and a characteristic activity, namely planting oaks (and other native trees) around Philadelphia on abandoned or degraded land. Basically, we walk around with oak seedlings sprouting out of our backpacks to restore invasive-dominated areas.

Our first time planting, we only took a few oaks. The next time, we mapped their locations so we could check on them later. By the third planting, we moved further afield, beyond our immediate neighborhood, and added additional species like black cherries and native mulberries. Along the way, we’ve developed a few rules for planting: only native species, only degraded lands, rarely on private property and on land where there is a good chance the trees won’t be cut down. It is a wholesome and creative, if not a bit irreverent, solution to a real and terrifying (but under-publicized) environmental emergency: the biodiversity crisis.

To put it simply, humans are destroying biodiversity all across the globe at an unprecedented rate. Populations of flora and fauna are plummeting and extinction rates are skyrocketing. All causes come back to human activity. We are recklessly transforming ecosystems by fracturing and destroying habitat; we have let invasive species take over and outcompete native plants and animals; and we continue to emit dangerous levels of greenhouse gasses, transforming the climate to which species have adapted over millennia.

While biodiversity loss is a global problem, the roots of the crisis are primarily local. This means we can solve the problem locally, too. When you drive around Philadelphia, look more closely at the lands you pass. You will find forgotten corners, vacant lots, road margins and other property that is covered in mowed weeds or overgrown with nasty invasives, such as stiltgrass, phragmites reed, knotweed and porcelain berry. Imagine all of those degraded environments restored with healthy native vegetation.

Hence our project: Oakify Philadelphia. Plant a few trees now and you will see change very quickly: the insects will come back, next the songbirds, then the raptors and mammals, and soon enough, an entire food web will return.

Why oaks as opposed to other plants? All native plants support wildlife, but some support more species than others. Trees typically support more insects than herbaceous plants, and oaks are by far the best North American trees at this, according to Douglas W. Tallamy, author of The Nature of Oaks. (Native wildflowers are also needed to support the insects’ whole life cycle). The genus of oak trees, Quercus, hosts 557 species of butterfly and moth caterpillars in the mid-Atlantic region, and across the entire U.S., that number rises to more than 900. These caterpillars are an invaluable food source for a large number of songbirds, from warblers and wrens to chickadees and cardinals, many of which are now in decline. Oak trees also provide natural nesting sites for birds and mammals and their acorns are eaten by a wide range of wildlife including wild turkeys, blue jays, chipmunks and flying squirrels. They really are the king of trees.

Join us in Oakifying Philadelphia, or start a chapter wherever you live! On road edges, in overgrown urban lots and even your own backyard, planting trees is a simple action you can take to help restore biodiversity.

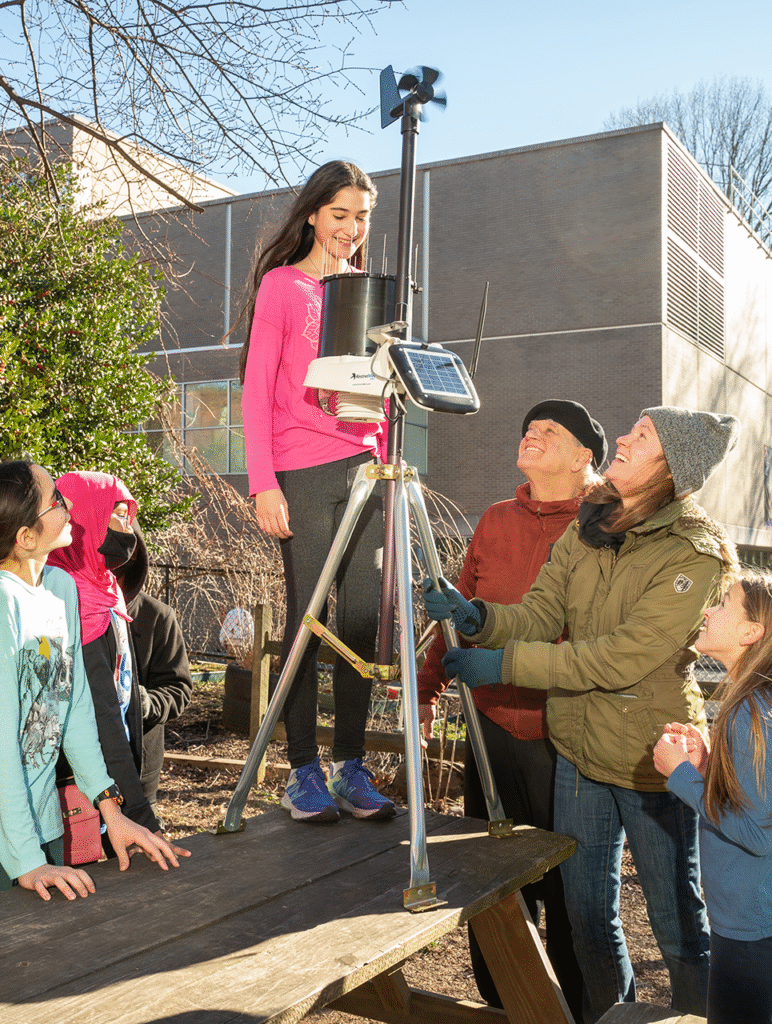

Here’s how to get involved:

1) Find a plot of land near you that is overgrown with invasives or simply just grass that could instead be a functioning ecosystem. Maybe it is your own yard! Even a small space will do, though, ideally, trees should be planted at least 10 feet apart. (To learn about planting natives, check out here or here).

2) Purchase some trees native to your area (we recommend starting out with mostly oaks), at a local nursery or somewhere online. We recommend Edge of the Woods or Good Host Plants, and when we can’t find a species locally, we buy saplings from NativNurseries (though they market to deer hunters, the website offers great species at good prices).

You can also grow trees yourself. Collect some acorns in the fall from a nearby park or nature preserve, plant them in small pots (ideally in a rich mixture of compost and soil) and place them on a windowsill that gets a fair amount of sunlight, or use artificial grow lights. They will likely germinate in 4 to 6 weeks. Wait another month or two before planting them to make sure they are sturdy.

3) Start planting. You can plant trees most times of the year, just not when it’s freezing or extremely hot (the ideal temperature is 50˚ Fahrenheit). Bring a trowel and a pair of gloves. Clippers for clipping invasive vines may also come in handy. If there is a deer problem where you are planting, you can order tree tubes that protect the saplings from being eaten. Be sure to order tubes made of paper or recycled materials like these, as new plastic is harmful to the environment.

4) Monitor the site. Come back to your plantings when you can to make sure the trees are staying healthy (if it hasn’t rained for several weeks, bring a jug of water). Many of your seedlings may grow to be large trees for your children and grandchildren to enjoy!

5) If doing this on your own feels overwhelming or you want to make new friends while you plant, join a volunteer ecological restoration day with one of our local groups such as Friends of the Wissahickon, the Schuylkill Center of Environmental Education or Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust.

This sentiment and heartfelt knowledge is the wisdom we need for the joy that begins with that first step that begins local ecological restoration. I see the hope that this path forward brings. Yes, it makes me proud and happy. The journey at the beginning may seem uphill but the years pass and Nature embodies the resilience that we humans can only learn from and try to practice….. if this, then that: unique, recognizable, complex, predictable, patterning…. human words trying to capture the ecological symphony of restoration locally.