It would be nice to imagine that all the clothes in our closets and dressers — let alone the endless items lining the shelves of countless retail shops — spring forth fully formed. Or, if that fantasy goes too far, to at least believe that our clothing is manufactured with some level of respect for workers and the Earth.

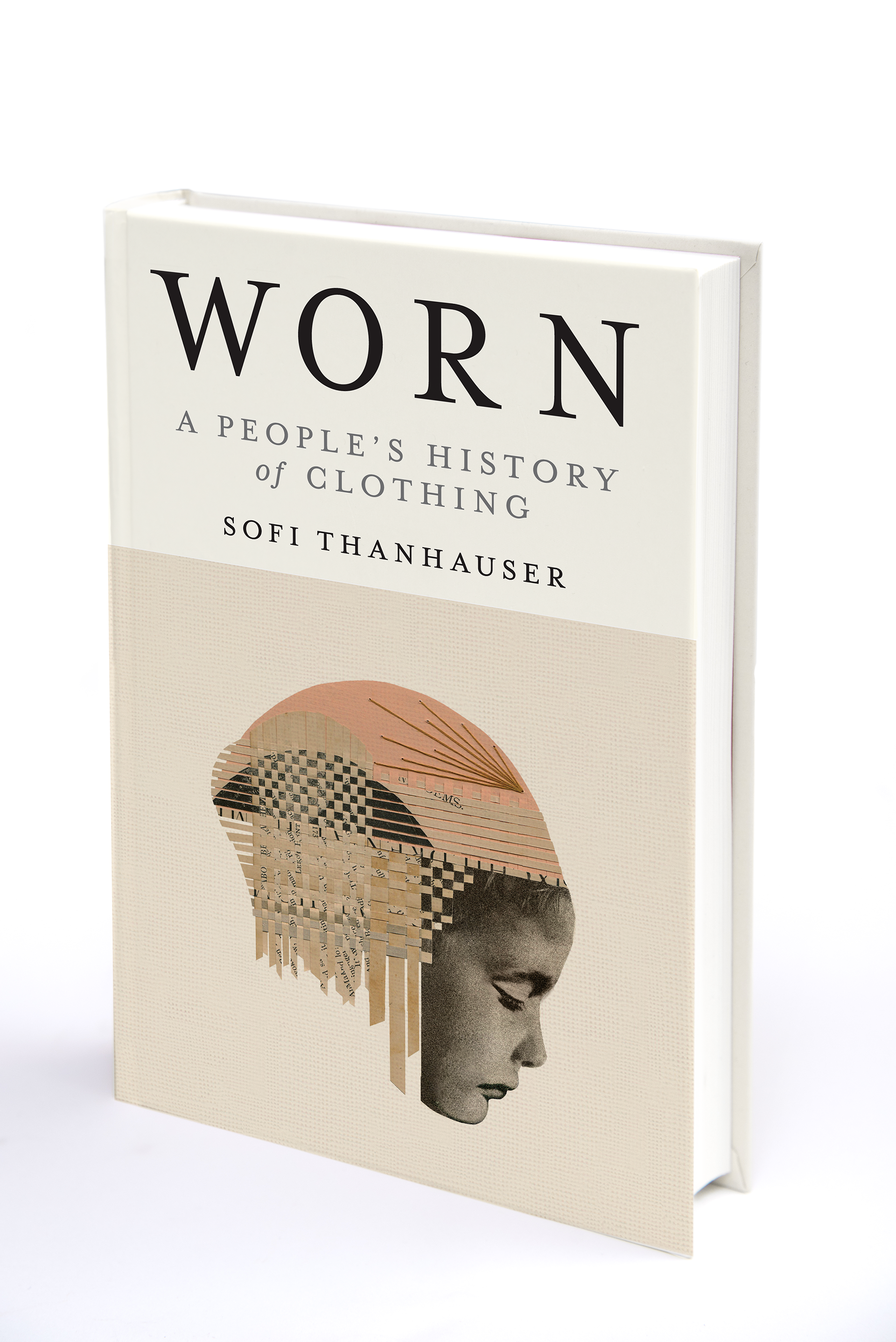

Sofi Thanhauser’s historical look at the production of clothing from before the Industrial Revolution to the current day will disabuse you of any such ideas. Human exploitation (most often women and girls) and environmental degradation remain central to the production of clothing today.

Grid publisher Alex Mulcahy caught up with Thanhauser to discuss her sweeping 2022 book, “Worn: A People’s History of Clothing.”

Your book has been called the “Omnivore’s Dilemma” of clothing. What are the similarities between fast food and fast fashion? I think that I must have already had a sense of how the problem of textiles could be considered an agricultural problem before I encountered Michael Pollan or even Wendell Berry, who actually to me, is the grandfather of us all, and someone upon whom Michael Pollan relied.

But clothing and food are both big fundamental needs that humans have that are increasingly being met by really wide, far-flung global supply chains that used to be met on a fairly local scale. And they both have really big problems with labor, and they also both have really big problems with the way they’re treating the land.

Speaking of labor, the industrial worker has not fared well, and it seems largely because capitalism is so slippery about avoiding unions. I think that’s right, but at the same time, one of the stories that I wanted to tell in “Worn” was how it wasn’t really capitalism as some kind of pure entity that’s separate from the nation state. For example, in the ‘50s there was this influx of Japanese goods and it seemed like they came out of nowhere. They’re cheaper, so we buy them. It’s purely a market story. But really there’s quite a political story to be told there.

The U.S. State Department in occupied post-war Japan made a decision to not only rebuild Japanese textile capacity, but to open the U.S. market to the products of that industry and allow the U.S. Southern textile mills to suffer and ultimately to go under in the name of Cold War containment, because we were more interested in making sure that Japan and later other countries in the Far East had viable industries and didn’t “fall to communism” than we were interested in saving our textile industry. So it’s capitalism, but it’s also state policy that went into the globalization of the garment industry in the post-war period.

And that policy really set the stage for exponential growth in production and consumption. What retailers and manufacturers and advertisers have found is that people have an unlimited craving for clothing. So when prices dropped really dramatically in the United States after the end of a quota regime, called the Multi Fiber Arrangement, everyone was actually surprised at what happened. The price dropped in half and people without missing a beat started buying twice as much. So the appetite is unlimited. And I’m not saying that to blame or shame because clothing is fabulous and why wouldn’t we want more of it?

It was illuminating to learn how the American Civil War had profound impacts globally, particularly on British and Russian imperialism. Until the Civil War, cotton textile manufacturers in the North of the United States, as well as in European countries and in Russia, were immediately reliant on American cotton. There was also a widespread fear — it turned out to be a legitimate fear — that relying on a slave-based agricultural system was not really going to be the most stable bet. Even though there had been some gestures to try to diversify supply before that moment, it hadn’t really gone anywhere. But then suddenly it had to, because there was no way to get this really abundant supply of cotton out of the South. So the British turned to India, where they had already set up colonial rule and attempted to force farmers who were growing vegetables and doing subsistence farming into farming export cotton, which had really catastrophic results for those farmers. And in Russia, it attended the expansion across the Asian continent and places like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which became major supply areas for raw cotton for Russian industry. There were big colonial pushes and a lot of violence exerted to regain a supply of raw cotton for textile mills.

If we think about sociologically why women are expected to dress a certain way today, it really goes back to this idea that you’re not economically independent.”

— Sofi Thanhauser

Women are central to the story of clothing, both as consumers and as producers who suffered as manufacturing shifted from craft to industry. What is the legacy of that? If we think about sociologically why women are expected to dress a certain way today, it really goes back to this idea that you’re not economically independent. I don’t know if you’re familiar with “Succession,” the HBO series, but there was some writing about Shiv’s clothing and she dresses in a way that’s pretty muted and not really out to impress. And she is independently wealthy. Like she was born with so much money and power, she’s never going to have to dress in a certain way to get it from anyone. And it was like drawing this equivalence between what a power play can look like for a woman when she doesn’t need anyone to approve of her appearance.

Something that’s bothered me really from early on and been like a hobby horse of mine, is the way that clothing and fashion are associated with women, and that they’re both associated with a lack of seriousness and a lack of intellectual depth, as though somehow they’re not real subjects. I would argue that clothing is at the root of this colonial project.

The history of rayon manufacturing — and how it poisoned and continues to poison workers — was one of the hardest stories to read about. There’s a chemical involved called carbon disulfide, which is a powerful neurotoxin. If you are exposed to it at unsafe levels, you can lose a lot of important parts of your brain function, essentially, which is what happened to generation after generation of worker, not because it’s necessary, but because the proper ventilation costs more money. So it isn’t that we couldn’t get this perhaps valuable industrial product unless we sacrifice the lives of workers. We just wanted to do it without investing in the proper ventilation.

Something that I find probably the most depressing when I look at history — but also has to do with why I care about telling history — is that sometimes the same thing is discovered over and over and over again and then forgotten, and often forgotten because of a large application of political violence. That is something that I see a lot in women’s movements and feminism. There is a certain demand or advance and then this incredible wave of violence and then it’s got to be rediscovered 20 years later or 100 years later by another group of people. So that story to me was and is a very sad one because of the ways that people choose to look away from really simple things that could be done to ensure human safety. And it just places you really close to the kind of bone-chilling decisions that are sometimes made in the depths of corporations to take it as given that some of your workers will go insane or die, and it’s okay because it doesn’t affect your profit that much.