Like a human starting to experience Alzheimer’s disease, a deer in the early stages of chronic wasting disease doesn’t look all that sick. You’d have to spend some time with it to notice anything amiss. But in both illnesses, once it starts, there is no stopping the degeneration of the brain tissue and further outward decline.

Chronic wasting disease, or CWD, got its name from its end stage, when the afflicted cervid (any member of the deer family, including elk, moose and caribou) drools uncontrollably, stares off into space, and, no surprise, wastes away.

The deer sheds infectious prions through its feces and bodily fluids during the couple of years it can take to reach that state. After it dies, its carcass remains a source of these prions, which can linger in the environment for years.

CWD was first discovered in captive mule deer (Western relatives of Pennsylvania’s white-tailed deer) at a Colorado research facility in 1967 and soon after in elk, also held in research facilities. In 1981 a wild elk with CWD was found in Colorado, and since then the disease has picked up speed, like a boulder careening downhill and crashing across the landscape. It now infects cervids in 29 states and two Canadian provinces. In Pennsylvania, infected deer have been found in 21 counties. As it rolls east, the disease could end deer hunting as we know it.

A Spongy Disease

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is caused by a mutant prion. Prions are proteins found inside animal cells. All proteins are chains of amino acids, and they fold in specific ways that help determine their function. The faulty prions that cause CWD cause other prions inside brain cells to misfold. This ultimately kills the cells and leaves holes in the brain tissue, hence the “sponge” in the official name for illnesses like CWD: transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE). The same is true for kuru and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, aka mad cow disease) in cattle, and scrapie in sheep and goats.

The End of an Era?

“If your animal tests positive for CWD, do not eat meat from that animal,” states the Centers for Disease Control. Though so far no human illness has been connected to eating venison from CWD-positive deer, other prion diseases as well as lab experiments investigating CWD transmission offer reasons to both hope and worry. Humans have been infected by eating cattle with mad cow disease. However, apparently no one has caught scrapie from eating mutton or goat, though the disease has been around for hundreds of years.

Macaques that researchers exposed to the CWD prions from infected deer (either orally or by injecting it directly into the macaques’ brains), did not get infected. Squirrel monkeys whose brains were injected by the same researchers did get sick, which demonstrated that it is technically possible for CWD prions to cause illness in primates. That said, the squirrel monkeys also got sick from scrapie prions delivered in the same way. And of course humans eat venison; they don’t inject it into their brains.

“I’d hate to go to the store and buy beef,” says Brad Gates, a Philadelphia hunter and wildlife expert who serves on the Friends of the Wissahickon Deer Committee. If CWD reached where he hunts in the Philadelphia area, “I would keep hunting,” he says, “but every deer I kill for food or to give away I would have tested.” He says he’s not sure if he’d keep hunting if rates got really high. “If I get three or four in a row [testing positive for CWD] and I’m in it to fill the freezer … that would get old.”

“I am a meat hunter,” says Jim Moore, who has been hunting in Chester County for almost 70 years. “I would still go hunting if the meat was okay to eat. Otherwise, I wouldn’t bother.”

Non-hunters might not care if hunters give up on killing deer, but a sharp decline in hunting — already fading in popularity — could undermine important streams of conservation funding that come from hunting license fees and from taxes on hunting equipment. “CWD has the potential to have major impacts on deer populations across the U.S.,” says Field. “It could have major impacts on our ability to keep hunting and conservation funding across the U.S. … Anything that would reduce hunter participation would reduce funding for conservation.”

CWD is highly transmissible but it doesn’t move that fast across the landscape until you take an animal and put it in a trailer.”

— Aaron Field, Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership

CWD Spreads in PA

As CWD outbreaks flared up in Western Maryland, West Virginia and New York, it seemed like Pennsylvania had been spared, but in 2012 the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (PDA) found an infected deer in a captive deer facility in Adams County, about 100 miles west of Philadelphia. Around the same time, the Pennsylvania Game Commission found CWD in two wild deer in Bedford and Blair Counties, about 175 miles west of Philadelphia.

Deer are often seen as a symbol of the wild, but they are also livestock. There are 753 captive deer facilities in Pennsylvania according to the PDA, second in number only to Texas. A few of these are petting zoos or hobby farms. Others produce products such as doe urine that some hunters use to lure in wild bucks. Some facilities are known as “high fence” operations or as hunting ranches. There, in a controversial practice frowned upon by many traditional hunters, clients can pay to shoot captive-raised bucks that are bigger and have larger antlers (many freakishly so) than what they can usually find in the wild. Other facilities selectively breed deer and sell them to the high fence operations.

The Game Commission established Deer Management Areas (DMAs), zones around the CWD cases with more-intense monitoring and restrictions limiting the movement of deer or their parts out of the zones. The PDA oversaw the quarantine and “depopulation” (killing) of the Adams County facility’s deer herd. One of those culled deer tested positive as well, bringing the total for the facility to two.

It is unclear how Pennsylvania’s initial outbreaks got started. The shipping of deer that is inherent to the captive deer industry could have delivered the infected deer to the facility. “CWD is highly transmissible but it doesn’t move that fast across the landscape until you take an animal and put it in a trailer. That’s how you get to new states and counties,” says Aaron Field, director of private lands conservation for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, a national hunting-focused nonprofit.

In Blair and Bedford Counties, the disease could have spread north from outbreaks in nearby Maryland and West Virginia, but it also could have been transported by people bringing dead deer back from hunting trips and, after butchering the carcasses, tossing the scraps in the woods. “I should say hunters need to be part of the solution, too,” Field says. “We can’t be moving infectious tissue around.”

Fighting the Spread

CWD outbreaks can get out of control quickly. “The 1-4% [rate of infection in wild deer] range is considered manageable, but when you start to hit that 5% level, you start to see the cat get out of the bag,” says Torin Miller, senior director of policy for the National Deer Association, which advocates for wild deer, their conservation and deer hunting. “So there are implications to not doing enough, and we see that where it has gotten out of control.”

The Adams County outbreak was apparently nipped in the bud. After five years of testing turned up no new cases in the DMA, the Game Commission considered it extinguished.

The Bedford and Blair county outbreak, however, has only grown. That DMA now covers all or part of 19 counties in West Central Pennsylvania, and the Game Commission considers CWD to be established — no chance of wiping it out — in all or part of five of those counties.

It’s really sad. They’re very skinny, they’re stumbling, drooling, losing their fear of humans. It’s definitely a hard thing to see.”

— Andrea Korman, Pennsylvania Game Commission

“In Bedford County where we have the highest prevalence, near 30%, people are starting to see it,” says Andrea Korman, who oversees CWD for the Game Commission. “It’s really sad. They’re very skinny, they’re stumbling, drooling, losing their fear of humans. It’s definitely a hard thing to see.” Based on anecdotal observations, Korman says that when CWD initially pops up in a new area, local hunters tend to heed the alarms, for example by submitting samples (deer heads deposited in special dumpsters) for testing. After a little while the issue fades to the background, only to be taken seriously when obviously sick deer are impossible to ignore.

Infected deer have been discovered at captive facilities in four other areas of Pennsylvania, including in Jefferson County, where wild white-tailed deer were later found to be infected, raising concerns that the disease had passed across the captive facilities’ fence lines. This outbreak is at the edge of the current range of Pennsylvania’s elk. Elk are native to Pennsylvania but were wiped out by hunters by 1867. The Game Commission reintroduced elk to north-central Pennsylvania in the early 1900s. Chronic wasting disease could mean the end of Pennsylvania’s elk, which number just 1,400.

Research indicates wild predators could help slow the spread of CWD by weeding out infected deer that are starting to miss a beat — it’s the weaker, slower individuals that tend to be killed by wolves and mountain lions. Even the fastest deer can’t outrun a bullet, yet a study testing mountain lion scat (poop) in Colorado found that they kill CWD-positive deer at a higher rate than human hunters, and computer modeling has indicated that wolves might do something similar. But there are no plans to reintroduce extirpated wolves or mountain lions in Pennsylvania.

You can’t get deer to socially distance.”

— Andrea Korman, Pennsylvania Game Commission

So we humans are left with cruder tools. “You can’t get deer to socially distance, so the fewer deer there are, the less interactions they have, and the less chance to transmit disease to each other,” says Korman. There are basically two ways that state agencies can end up with fewer deer: give recreational hunters permission to kill more deer, particularly does, or have professionals do it (“targeted removal”).

The hunting-targeted removal combination apparently worked to stamp out New York’s brief CWD outbreak. In 2005, after finding cases in two captive deer facilities in Oneida County (near Syracuse) New York responded within weeks, engaging both recreational hunters and professionals to kill more than 300 wild deer around the facilities. Two of those wild deer tested positive, but no cases have been reported in the state in the years since.

In 2012 the Game Commission did not respond with similar alacrity, as described in the state’s official CWD Response Plan’s account of the first wild outbreak. You can read the frustration between the bureaucratese lines: “[I]n addition to instituting the same DMA-wide restrictions and enhanced surveillance that had been applied to DMA 1 [in Adams County], recommendations were made to reduce deer abundance in the area … Unfortunately, these measures … were not implemented.”

Political and Social Barriers

Field, of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, says state wildlife agencies should act according to science. “They can’t be hamstrung by politics,” he says. “If you take a trained wildlife management professional and give them science to act on, they will come up with good policy.”

Although CWD is increasingly widespread, deer in the final stage of the illness are rare. A deer with its version of dementia is more likely to get killed by a predator (human or wild) or by a car, usually before it is obviously sick. A more visible illness might cause more alarm, but the public has to trust scientists that CWD is a problem. The COVID-19 pandemic and the backlash to public health measures have only made it more difficult for Game Commission scientists to convince hunters to go along with new rules and recommendations.

It doesn’t help that hunters often oppose measures to reduce deer abundance, since that makes it harder for them to kill deer. “Management strategies that tend to reduce deer densities tend to get pushback,” Field says.

And of course the captive deer facility owners tend to oppose measures that impact their businesses. Miller and Field point to the best management practices developed by the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies as the gold standard playbook for managing CWD. The first recommended practice is to “Prohibit all human-assisted live cervid movements.” In other words, don’t transport any live deer. That measure would severely limit the captive industry, though, and Pennsylvania has not adopted it.

Instead, all captive deer facilities in Pennsylvania must enroll in either a state or federal CWD program that sets rules for record keeping, testing of dead deer and fencing requirements. Both programs have their shortcomings. Neither requires more than a single fence to keep the captive and outside wild deer apart, even though contact through fences has been identified by researchers studying CWD transmission as a potential way for the disease to spread into or out of facilities. And while the federal herd certification program requires testing for all animals that die for whatever reason, the state’s program only requires that 50% be tested, meaning CWD-positive deer could be escaping notice.

“All of the barriers are political and social,” Korman, of the Game Commission, says. “Everything with CWD becomes controversial.” She points to a recent attempt to ban the use of urine from captive deer, since urine from infected deer contains prions. Game Commission scientists backed the ban, but the captive deer industry rallied to oppose it. Ultimately the commission, made up of political appointees, voted against the urine ban. “I didn’t know my career would entail so much deer pee,” Korman says.

Pennsylvania’s response to CWD is further complicated by splitting deer oversight between the PDA (captive deer) and the Game Commission (wild deer). “In states like Pennsylvania, where deer are managed by different agencies, we see a disconnect between the two,” Miller says. For a possible solution he points to Minnesota, which in 2021 shifted captive deer oversight from its agriculture department to its department of natural resources.

Next Stop, Philadelphia?

It’s a dirty job, but every year the Game Commission pulls more than 3,500 dead deer off the sides of roads to test them for CWD. On September 13, 2023, the Game Commission announced that two such deer collected in Dauphin County (near Harrisburg) had tested positive, the first free-ranging deer east of the Susquehanna River detected with the illness. Now, no major barrier stands between the deer of the Philadelphia region and the incurable, highly-transmissible disease.

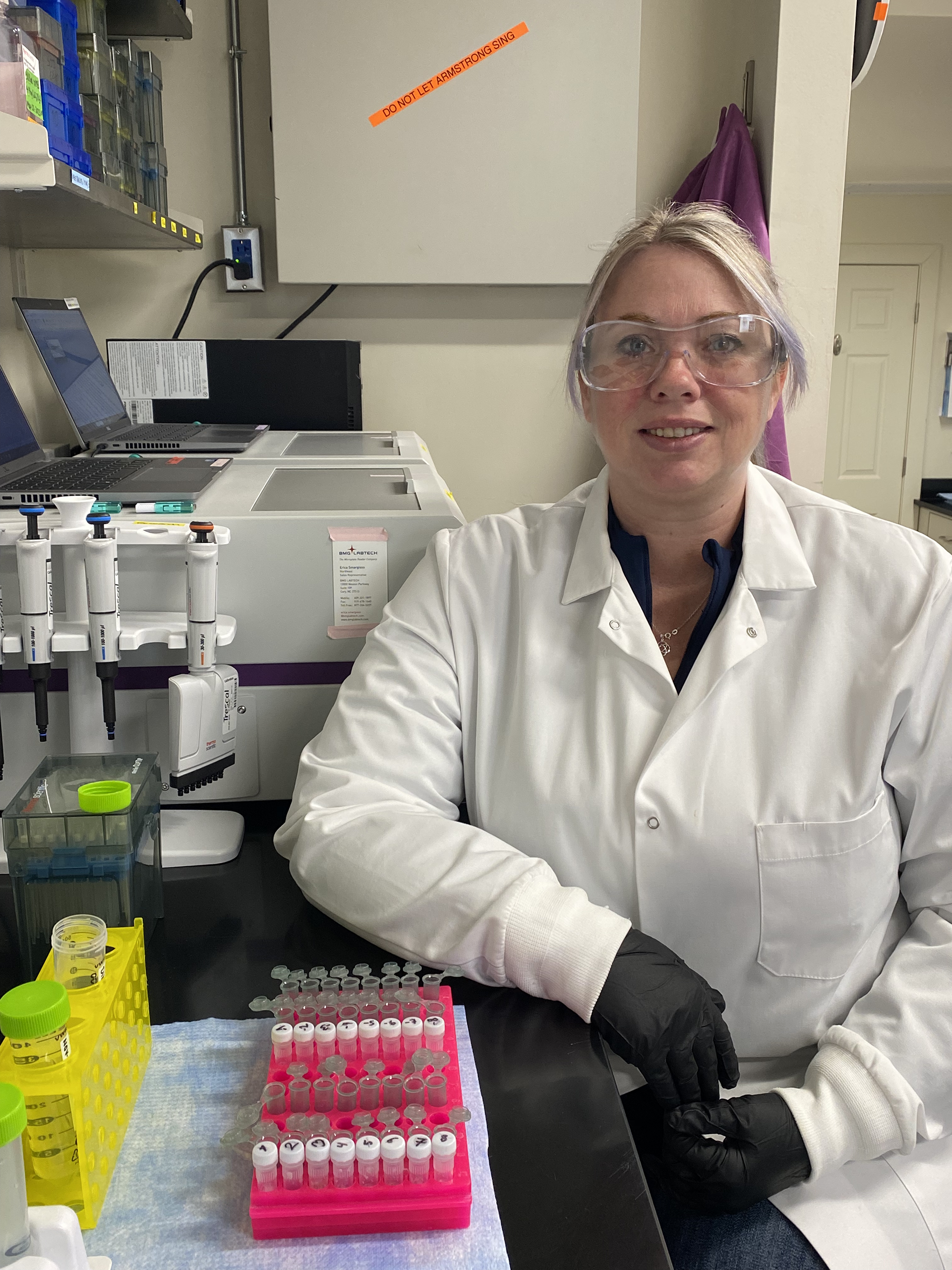

The University of Pennsylvania’s veterinary school in Kennett Square, Chester County, is helping to monitor the spread of CWD by testing samples taken from road-killed deer as well as hunted deer. “We test 10,000 to 12,000 samples per year,” says Dr. Michelle Gibison, who directs CWD research with PennVet’s Wildlife Futures program. Their lab is also working to develop faster and more sensitive tests.

Dogs might also play a part. The keen-nosed canines can differentiate between droppings of healthy deer and infected deer. At some point, specially trained dogs might roam the woods, fields and yards of Pennsylvania, sniffing out new outbreaks.

Although CWD’s impact on wild deer and on hunting draws the most attention, the potential for prion diseases to jump species makes it a public health concern for non-hunters as well. The next species it jumps to could develop into a version that is more infectious in humans. “Right now it doesn’t appear to be zoonotic to humans,” Gibison says, “but BSE [mad cow disease] was something humans eventually got, so it might not go directly from deer to humans.”

It is impossible to say for sure when Philadelphians will see sick deer stagger out of Fairmount Park, but when the disease reaches the area, with its extremely dense deer populations, it will be even harder to control than in rural areas. “It’s definitely going to be a problem. The more deer you have, the more likely they are to transmit it to each other,” Korman says.

The landscape of parks wrapped around neighborhoods, along with suburban deer populations living in backyards and narrow strips of greenery, limit the effectiveness of hunting and targeted removal.

Experts Grid interviewed couldn’t think of any other similar urban areas with CWD outbreaks so far, but they pointed to the experience of captive facilities with their artificially-dense herds as offering a possible view of the future. For example, in one Iowa hunting ranch stricken with CWD, 280 out of 356 deer tested positive in 2014.

Here in Philadelphia where we have to fence deer out of our parks to regenerate forest canopy and in suburbs where the animals devour almost everything gardeners plant in the ground, it might be hard to imagine that 120 years ago, Pennsylvania had virtually no white-tailed deer. A combination of deforestation and unlimited hunting had nearly wiped out what is now the state’s official animal. Regrowth of forest, restocking by Game Commission, and enforcement of hunting regulations led to the recovery of white-tailed deer, one of the state’s greatest conservation feats.

For now, Pennsylvania still has plenty of white-tailed deer (1.5 million), though CWD has begun to cause populations of mule deer to decline out West, where it has been established for a longer time. The same could happen here with their white-tailed relatives once the infection rates increase.

Although hunters are the people who come into contact with deer most often, everyone can get involved with slowing CWD’s spread across the commonwealth. “As the Game Commission, we tend to focus on hunters and what hunters can do,” Korman says, “but there are things the general public can do.” Anyone who sees an apparently sick deer should call the Game Commission (1-833-PGC-WILD). The same goes for reporting road-killed deer, which the Commission can have tested to monitor for new CWD outbreaks. Though it can be tempting, “don’t feed the deer,” Korman says. “That passes along all kinds of illnesses.”