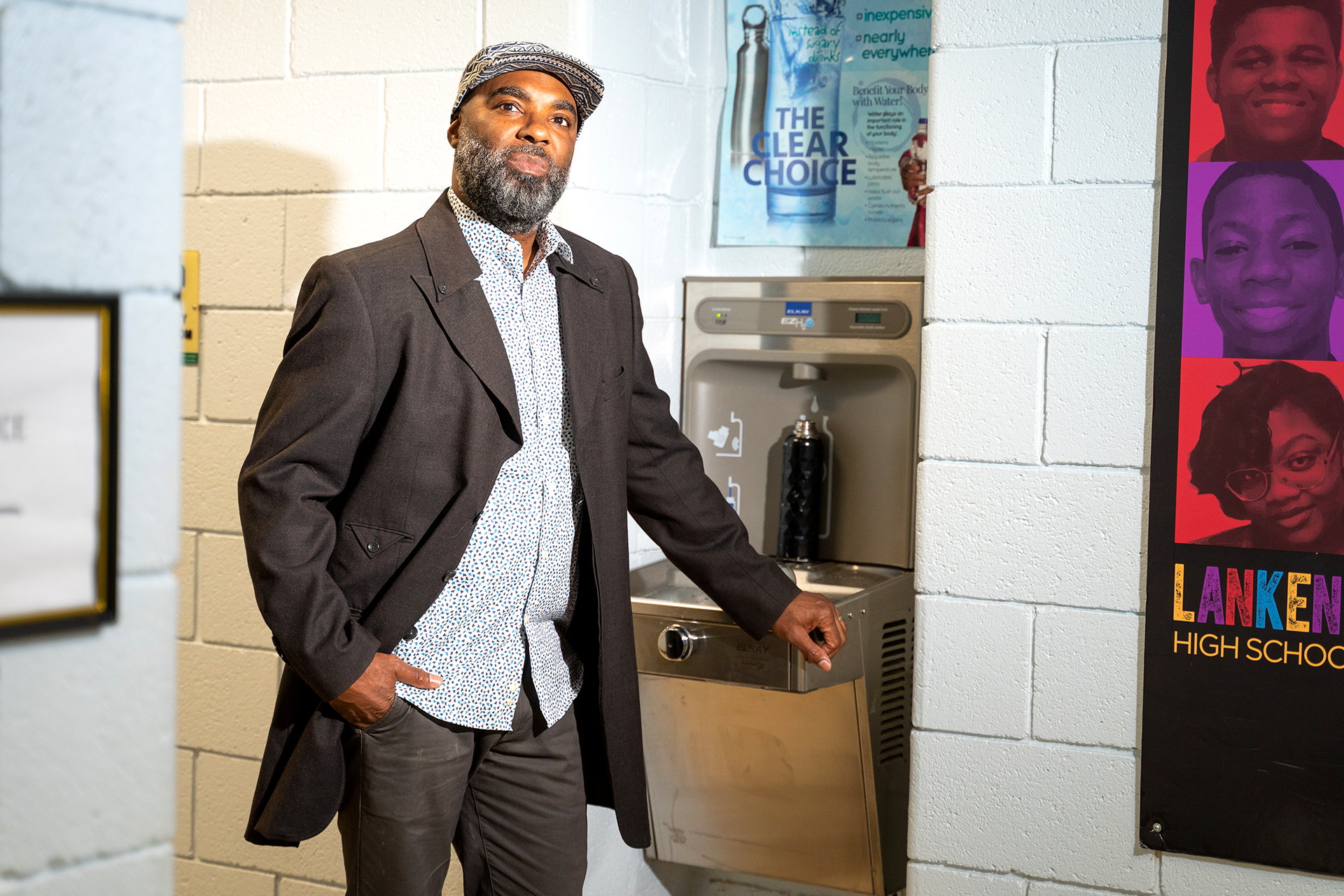

Dwayne Wharton was tasked with helping to solve one health care crisis affecting kids when he discovered another.

Wharton was working for The Food Trust in the mid-2010s, and that organization’s goal was to reduce the number of sugary beverages, especially soda, kids were drinking. They encouraged students to drink more water from the ubiquitous water fountains. But many kids, Wharton learned, were reluctant to drink from the fountains.

“We spent enough time in schools to know about the old water fountains,” Wharton says. Students told him that some were used as trash receptacles, and some fountains were turned off and had “do not drink” signs on them. “Kids were saying, ‘If that water over there isn’t safe, why would this water be safe over here [at functioning fountains]?’ Kids were bringing this up.”

Compared to other public health threats, cutting back on sugar from sweetened drinks appears to be pretty simple: drink free tap water instead. That only works, though, if people trust the tap water, and it was clear that Philadelphia youth did not.

As The Food Trust was raising students’ concerns about water quality in schools, Philly environmental leaders and politicians were sounding alarms about another reason to dodge the school tap water: it could be contaminated with lead.

Kids were saying, ‘If that water over there isn’t safe, why would this water be safe over here?”

— Dwayne Wharton, former Food Trust director and lead-free schools advocate

“I think the way this started goes way back to Flint,” says David Masur, executive director of PennEnvironment. In 2013 Michigan state officials overseeing cost-cutting measures for Flint’s city government switched to a new, cheaper water source without considering that the new source would be slightly more corrosive, dissolving lead out of the city’s old pipes and thus poisoning the water supply for the city’s residents, more than half of whom are Black and more than a third of whom live below the federal poverty line. “I think Flint … called into question something we took for granted for a really long time: that when we turn on the tap that water is safe,” Masur says. Thanks to the crisis in Flint, it dawned on Philadelphians “that lead in drinking water was still fairly common and it didn’t matter that much where you live, whether you were in a blue district or red district or purple district.”

The Problem with Lead

In some ways lead is an incredibly useful metal. It makes paint more opaque and water-resistant. In gasoline it stopped engines from knocking. It is dense, making it handy for fishing weights and bullets. It is soft, melts at a relatively low temperature and resists corrosion, making it a convenient material to form pipes, as the ancient Romans discovered. The Latin word for the metal, plumbum, gives us our words for water pipes (plumbing) and the people who fix them (plumbers).

The problem is that lead is a potent neurotoxin. High levels of lead have been widely recognized as toxic since the late 1800s, but in the 20th century it became clear that chronic exposure to low levels of lead is particularly harmful to children, causing developmental delays and behavioral health problems later in life. This realization led to efforts to get rid of lead where children could be exposed, including a national ban on lead paint in 1978 and a phase-out of leaded gasoline starting in the 1970s. These measures resulted in a steep decline in lead exposure, celebrated as a major public health victory.

Today most of the attention on lead focuses on exposure to flaking paint and contaminated dust that kids encounter in old houses and apartments, which is one reason that Flint’s lead crisis came as a wakeup call. Philadelphia has a lot of similarities to Flint, including an old water system built when lead was widely used in plumbing.

In an aging city like ours we had to take positive, proactive action on this.”

— Helen Gym, former City Councilmember and current mayoral candidate

“Right before I came into office the tragedy of Flint, Michigan, had just come to light, when an entire town had been poisoned through a change in the water by the government,” says Helen Gym, a current mayoral candidate who served on City Council from 2016 to 2022. “I made a vow back then that we wouldn’t become Flint. In an aging city like ours we had to take positive, proactive action on this.”

Gym, who by the time she ran for City Council had been a longstanding advocate for public school students, held a series of education town halls. At Sayre High School in West Philadelphia, students talked about the water fountains. “This group of students wanted to talk about what it was like to go to school and have water fountains shut off or fountains that did exist put out murky water.”

“We ended up doing a meeting in City Hall with a group of middle and high school students who addressed the School Reform Commission [the body that then oversaw Philly public schools],” Gym says. “When you look into the eyes of a 10-year-old who nervously wrote out her comments and asked leaders to fix the water in her school, you can’t look away from that.”

In June 2016 Gym introduced a bill to City Council mandating that schools test water from fountains for lead and to shut off any that had levels higher than 10 parts per billion, at the time the strictest standard in the country.

The school district itself kicked off a drive in August 2016 to install three hydration stations (filtered water fountains that also filled bottles) in each of its 218 schools within the year. “The school district immediately became a partner on the hydration stations,” Gym says.

Parents of school district students didn’t want to wait while their children drank tainted water. They also began advocating for improvements. At the Henry C. Lea School (grades Pre-K through 8) in West Philadelphia, the home and school association (HSA) began raising money to buy hydration stations. “The process for putting in water stations was so slow and bureaucratic, I said as parents can’t we just buy a station, just one or two? Surely our building engineer could install them,” says Adam Weaver, a Lea parent and member of the HSA. “Some of it is you think about your own kid, but we’re in a privileged position. We can send our kid in with a big water bottle, but what about the wider school community?”

In the end the HSA raised enough money to pay for two hydration stations, but a principal transition slowed down efforts to install them. By the time the new principal had settled in, the district had installed three hydration stations, and the HSA shifted its focus to buying water bottles for students to bring to school and fill with the filtered water.

Philadelphia students learn in buildings that are, on average, 70 years old, according to Reggie McNeil, the school district’s chief operating officer. Sayre’s building dates back to 1949. About a mile away, the oldest section of the Lea School was built in 1914. School buildings like these and the city water system that feeds them have old pipes with lead soldering, McNeil says. It’s an “old piping system and old material. The lead is coming from that.”

The district, chronically scrambling for operating funds due to the city’s relatively poor tax base (compared to wealthier districts such as neighboring Lower Merion) and underfunding from the state, has fallen behind on maintaining its old infrastructure. Decades’ worth of deferred maintenance has piled up. A 2017 report assessing the state of the district’s schools found that it would cost $4.5 billion to fix everything.

Although removing lead from school pipes would, on the face of it, seem to fix the problem, McNeil says that that would entail ripping out entire plumbing systems, and there could still be lead coming from the city’s pipes that feed the schools. Filtering the water where students get it is, on the other hand, a simple fix. “This is one of the best ways we can do that, to give them a chance to drink clean, filtered, cool water right now,” McNeil says.

Thanks to the 2016 legislation, ultimately signed by Mayor Jim Kenney in the beginning of 2017, the district began posting the results of its water fountain tests. “Sunshine is the best disinfectant,” Masur says of the law’s requirement to share testing data. “We have to have that to make good decisions. The school district had done some testing but didn’t share it. Helen Gym’s law said they had to test all the outlets in a 60-month period and within 30 days post on the website, and where they found elevated levels of lead take the fountain offline and fix it.”

At Lea, the district ran its tests in February 2019, checking the eight hydration stations that had been installed by that point as well as one older water fountain and three sinks in the nurse’s office and lunchroom. All came in under the 10-parts-per-billion threshold. The hydration stations reduced lead to undetectable levels, and the older water fountain also had undetectable levels though the sink faucets had levels of 1.4, 1.5 and 5.4 parts per billion.

Although 10 parts per billion was the threshold for shutting off a drinking water outlet, advocates argued that, as the World Health Organization points out, there is no safe amount of lead. In early 2022 PennEnvironment and the Pennsylvania Public Interest Research Group analyzed the district’s published numbers and issued a report criticizing the district’s results as well as its slow testing pace.

According to the report, as of February 1, 2022, the district had tested 29% of its schools and 61% of the fountains and sinks tested had detectable lead levels. The report also argued that the district’s testing methods could be understating the actual lead levels in real-world use of the fountains. The report pointed out that there is no safe level for lead; even low levels of lead can lead to cognitive deficits and behavioral problems later in life. It would be safest to replace all older faucets with filtered hydration stations.

In March 2022 Gym introduced legislation that would require the school district to do just that. “We wanted to accelerate things,” she says. “Like anything within a big system, things slow down … In 2016–17 we passed back then what was the nation’s best standard at 10 parts per billion, but we shouldn’t tolerate any level if we know the filtration systems can reduce levels to effectively zero.” She says lead poisoning in schools was a problem they knew they could knock out quickly. “I don’t want to be talking about lead poisoning in schools in 10 years.” Mayor Kenney signed the legislation into law at the end of August.

In October the district announced that it had won a grant for $5 million from the EPA to pay for the last of the hydration stations: 755 on top of the more than 1,500 it had already installed.

According to the district, the hydration stations are simple to maintain. “Building engineers are qualified to remove and replace filters,” says Stephen Link, director of the district’s environmental office. “It takes five minutes.”

“We are excited about the changes we are a part of to remove lead in water,” McNeil says. “Our passion is that we want to provide a safe space for our kids and for our staff.”

Link points out that the hydration stations promote the use of reusable water bottles, reducing plastic waste from bottled water.

For the environmental advocacy community, the key lesson is that, in the end, it is best to skip testing and simply install filtered water outlets. “What we realized is lead is so pervasive, you’d have to test every outlet every year,” Masur says. “Actually it’s just cheaper to replace them all.”

Gym draws a broader message about setting goals for the city even when the resources to achieve them aren’t apparent. “When we are clear about our missions, we can go out and leverage resources to make it happen. We often don’t take on additional infrastructure projects because capacity isn’t there. That can’t be solely the reason we do or don’t do a thing,” Gym says. Once the City decided to prioritize getting lead out of school drinking water, it was able to find the money. “That’s the lesson of the grant … It’s not just about how much money exists. It’s about how well we do in exciting and catalyzing investments when this modernization effort we’re doing transforms the lives of young people.”