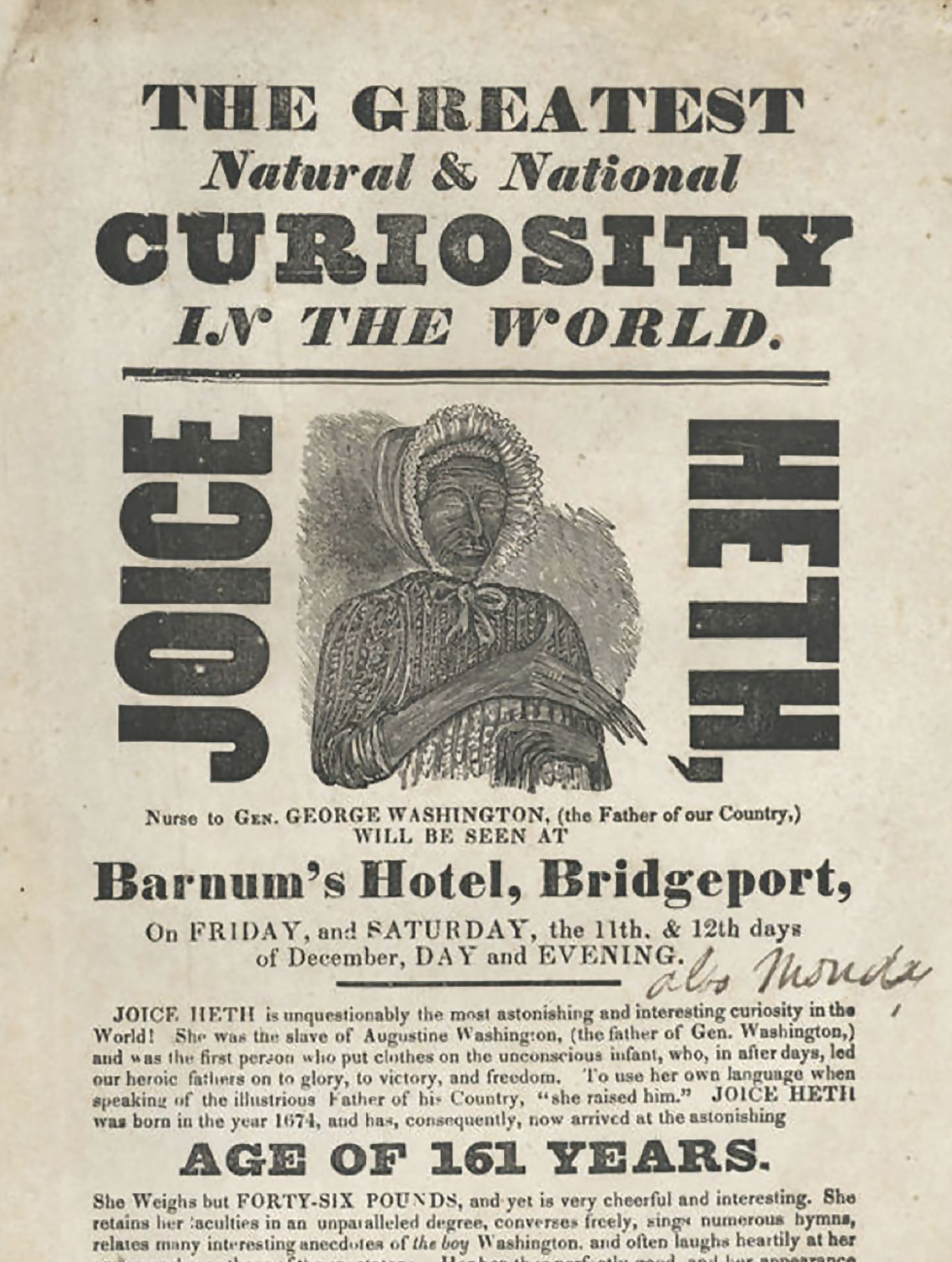

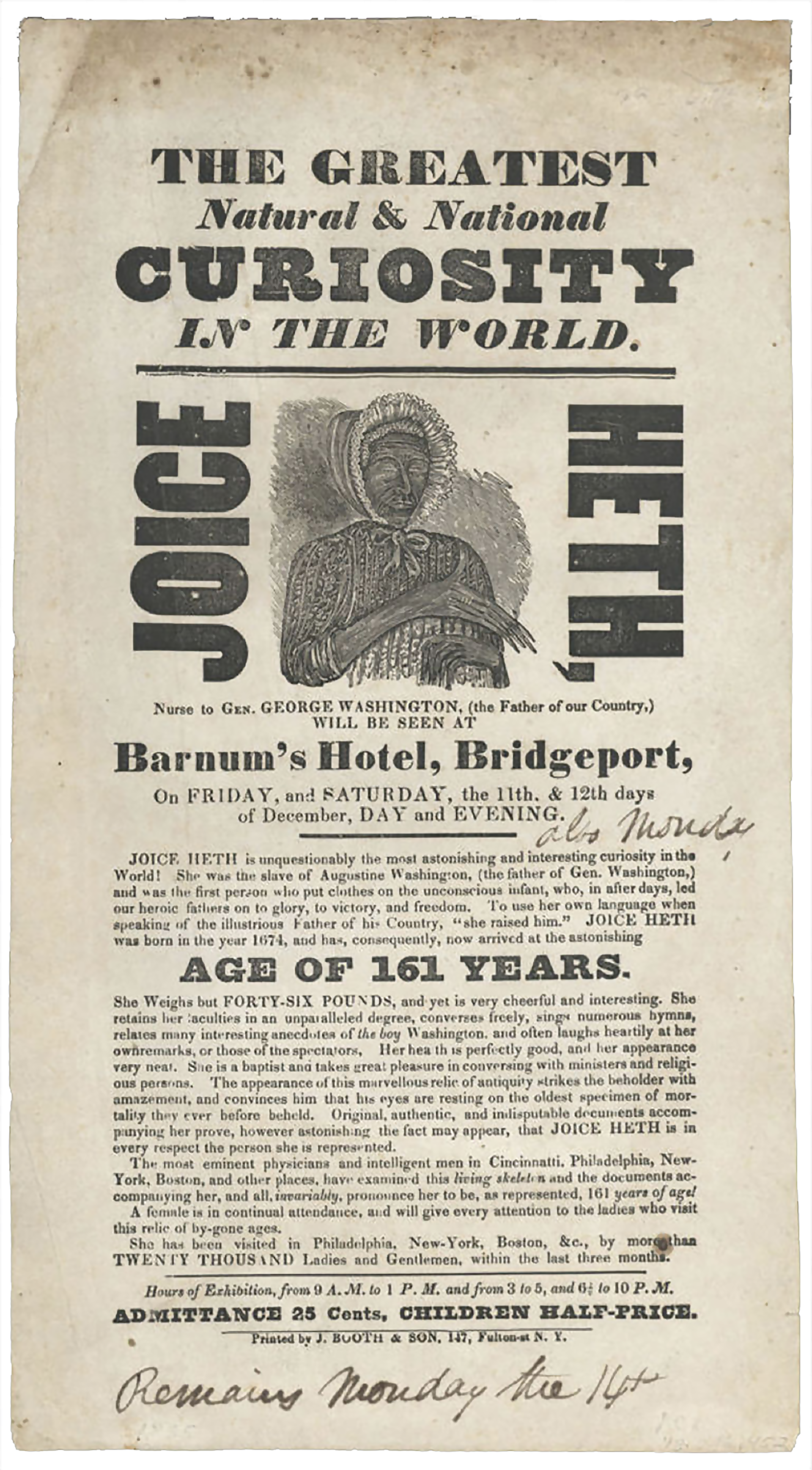

In 1835, future circus magnate P. T. Barnum and an enslaved Black woman he bought for $1,000 bamboozled the public, according to the impresario’s 1855 autobiography and Mark Bramble’s 1980 musical “Barnum.”

Barnum, living in New York, heard that the woman, Joice Heth, on exhibit in Philadelphia, claimed to be the 161-year-old former nursemaid of George Washington. Barnum rushed to Philly. He paid rapt attention as Heth assured all comers that she was once enslaved by Augustine Washington, George’s father, and that she was the first person to dress “little George,” Barnum’s autobiography says.

Heth’s claim hinged on her appearance.

“She looked as if she might have been far older than her advertised age,” Barnum writes. “She was … in good … spirits, but from age or disease, or both, was unable to change her position. Although she could move an arm, … her lower limbs were fixed in their position. She was totally blind, and her eyes were … deeply sunken in their sockets.”

Heth looked ancient, but seemingly not ancient enough for Barnum. Medical ethicist Harriet Washington says that he had Heth’s teeth pulled to make her look even older.

Even toothless, Heth chatted up the crowds.

“She would talk as long as people would converse with her,” Barnum writes. “She was quite garrulous about her ‘dear little George.’” Heth also sang hymns and smoked a pipe while on display.

Meanwhile, Barnum’s $1,000 investment brought in, on average, $1,500 a week — close to $50,000 in today’s dollars, estimates say.

Barnum’s exhibiting Heth sometimes raised hackles.

“She is the sole remaining tie of mortality which connects us with … [George Washington] and as such, we should … not suffer her to be kept for a show … to fill the coffers of mercenary men,” a reader complained to the editors of the New York Sun in August 1835.

As the nation lurched toward civil rights, Black performers with unusual bodies flipped the script.”

When Heth died in February 1836 Barnum cashed in on her corpse. He charged 50 cents per person to attend the autopsy to establish her age. The surgeon who performed it declared Heth to have been 80 years old at most.

Heth, whose looks and gab made money, was paid nothing. Barnum, on the other hand, used cash he’d earned exhibiting her to launch his career in show business. After Emancipation, however, as the nation lurched toward civil rights, Black performers with unusual bodies flipped the script. They kept more of the money that their striking looks earned. Their lives included courage, talent, kidnapping, court cases and straight-up fraud. Like Heth, several performers had a Philadelphia connection.

Consider conjoined twins Millie-Christine McKoy (1851–1912), born into slavery in North Carolina. Fused at the tailbone, they shared a single pelvis and weighed a combined 17 pounds at birth, according to their biographer, Joanne Martell, in “Fearfully and Wonderfully Made.”

Their lives included courage, talent, kidnapping, court cases and straight-up fraud.”

Visitors who descended on McKay’s farm to see Millie-Christine included John Pervis, who paid McKay $1,000 for “certain twins negro [sic] girls about ten months old.” The twins and their family changed hands several more times, and Millie-Christine became separated from their parents, Jacob and Monemia. Finally, Joseph P. Smith bought the “Celebrated Carolina Twins,” “pert and cunning” toddlers by 1853, only to have them kidnapped. Smith hired a private eye to find them.

Meanwhile, the kidnapper laid low, giving secret showings of the girls.

He “gave private exhibitions to scientific bodies, reaping … a handsome income,” the twins’ autobiography says. “He took us to Philadelphia and placed us in a small museum in Chestnut Street, near Sixth, … under the management of Col. Wood.”

In 1856, Smith got word that the twins’ manager at the time had them touring England. Determined to recover them, Smith bought the rest of Millie-Christine’s family. That December, he sailed to England with Monemia, the twins’ mother.

In January 1857 at the finale of one of Millie-Christine’s shows, Smith, an audience member and the American vice consul in London stormed on stage and wrenched the twins away from their manager, a Mr. Thompson. Bedlam erupted. Later, Thompson contested Monemia’s custody of Millie-Christine, but the English court ruled in Monemia’s favor.

Once back at Smith’s North Carolina home, Millie-Christine began performing under his management. Mrs. Smith helped polish the twins’ singing and dancing and broke the law by teaching them to read and write.

The Civil War stopped Millie-Christine’s touring. When it ended, the twins, 14 years old and free, began calling some shots.

“Now … [she] … set her own rules,” Martell writes. There would be “no more intimate examinations by curious doctors in every town.” In 1869 in Boston, Millie-Christine refused to let Harvard doctors do a physical examination of them. Later, they consented to a fully clothed visit to a Philadelphia medical school.

“In Philadelphia, Millie-Christine’s physician friend William Pancoast invited her to [a] teaching clinic at Jefferson Medical College,” Martell writes. “At age twenty-seven, Millie-Christine was of increasing interest to the medical community [because of excellent health despite being Siamese twins.]”

By 1882, Millie-Christine commanded $25,000 a season, according to an ad from the Great Inter-Ocean Railroad Circus, which featured them that year. That sum would have an estimated $727,000 of purchasing power today. Millie-Christine also presented their dancing and singing — one sang alto while the other sang soprano — in Europe for seven years, including command performances for British royals.

The twins bought the land where they were enslaved as children and built a 12-room house on it. They also built a church, organized a school for Black children and donated to several Black colleges, according to a descendant. “One thing is certain,” their autobiography says, “we would not wish to be severed, even if science could effect a separation.”

One question bedeviled Ella Williams, aka Madame Abomah (1865–1925?), born mere months after the Civil War ended: Should she remain a familiar oddity in Columbia, South Carolina, living near family and friends, with steady, low-wage work as a cook or join a circus as the world’s tallest woman, casting her lot with animal tamers, fire-eaters and tattooed wonders?

At 31, Williams, who probably stood between 6’9” and 7’4”, made up her mind. In 1896, English entrepreneur and animal trainer Frank Bostock “offered her such terms [for performing in the British Isles] that she accepted the engagement,” says the April 4, 1905, edition of the Thames Star, a newspaper in New Zealand, one of many countries where Williams sang.

Newspapers followed her travels. An article in the March 1, 1905, edition of New Zealand’s Wanganui Herald describes extraordinary accommodations made on the SS Afric for her trans-Pacific hop. It required “removing the bulkheads between two cabins [so she could lie down].”

Williams’s new status brought perks. “Abomah is not above … charming little [fashion] conceits,” said a November 24, 1904, article in The Mercury, a newspaper in Tasmania. “Abomah had plenty of lace … on the front of her blouse, two or three gold chains and rows of pearls.”

Australian promoters had to reckon with the country’s Immigration Restriction Act if they contracted entertainers of color, according to the September 10, 1904, edition of The Australasian. This act controlled the entry of Black and Brown persons into Australia. Promoters got exemptions for “the American giantess and the Fisk Jubilee Singers,” mentioned by name in the article.

At one point Williams had her own troupe. The Abomah Company of Entertainers included a ventriloquist, a magician and artists who performed “musical sketches.”

Williams toured South America, the Caribbean, Europe and major U.S. cities, including Philadelphia. She was performing in English music halls in 1914 when Britain declared war on Germany. She returned to the United States weeks before German Zeppelins bombed London.

Williams’s career spanned 30 years. A photo taken in 1925, the year of her last known appearance, shows her with Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey’s “Congress of Freaks” on Coney Island, thinner than in her heyday. No obituary has surfaced to tell when or where she died.

While Williams decked herself out for the public, Calvin Bird (or Byrd) wore a loincloth and a contrivance that seemed like an anomaly.

One story says that Bird, a tall “gingerbread-colored man” from Pearson, Georgia, got his start when he fell in with one of the four notorious Dedge brothers, doctors and dentists as well as murderers and counterfeiters from Georgia, according to the Ray City History Blog of April 17, 2013. John Dedge, D.D.S., born in 1865, was the most infamous of the clan. In 1901, Dedge and an associate concocted a plan to exhibit a “wild man from Central America.”

Another version of the story says that Bird decided to be a “wild man” and drew Dedge into the plan. A Philadelphia dentist is said to have made a bridge with fangs that Bird used during his act.

Dedge claimed to have brought back a “wild man” from a trip to Central America. Newspapers ate up the story. “This freak is a man with two well-developed horns … growing out of his head. … He also has two prominent tusks … in place of eyeteeth,” said the Atlanta Constitution on May 8, 1902.

Another newspaper gave a wry response to Dedge’s claim.

“It is an off year in South Georgia when Dr. Dedge does not announce some astounding piece of freak work,” the Waycross Journal quipped.

It seems that Bird’s carousing revealed the fraud. Police in Valdosta, Georgia, arrested him for firing a pistol in the street, says the Waycross Weekly Herald of March 22, 1902. Police discovered that Bird had an incision in his scalp where a thin piece of metal had been slipped under the skin: goat horns could be attached to knob screws coming out of the metal strip so that the horns seemed to grow from his head. Likewise, his tusks could be fastened to his eyeteeth so that they appeared to grow from his gums. Bird swore that he didn’t know how the metal strip came to be under his scalp.

Bird had plenty of company playing a “wild man.” Black “wild men” who ran around in cages and gnawed horse meat upped circus profits and their own wages.

“Say you’re a roustabout and the boss offers you a chance to earn extra cash,” says circus historian and author Fred Dahlinger Jr. “What do you do?”

Bird and Dedge, unmasked yet undeterred, toured the country and raked in money. Finally, Bird turned up at the Hospital of the Good Shepherd in Syracuse, New York, and asked a surgeon to remove the metal plate from his scalp, according to William C. Thompson in “On the Road with a Circus.” “The Wildman business had got monotonous, he said and … he had made enough money out of his deception to maintain him in idleness for a long time.”

Decades after the Civil War, Otis Jordan (1926–1991) from Barnesville, Georgia, fought his own battle: He went to court to protect his right to be in sideshows. Born with a rare condition, arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, Jordan had small, ossified limbs and only two normal fingers. He reached a height of 27 inches.

“My brothers carried me to school … until I was in the fifth grade,” Jordan reports in the pamphlet “Life story of Otis Jordan.” With his father’s help, Jordan designed a little cart pulled by two goats so he could get around on his own.

As an adult, he “learned to drive a car with special controls and … [had] a valid license,” Jordan writes. “I am good at small appliance repairs and small crafts. However, it was impossible for me to get a job until 1963 when a small carnival played my hometown.” Jordan signed on.

He developed an act where he rolled and lit a cigarette using only his mouth and lips. He worked in sideshows until Barbara Bogdan, a handicapped woman, was outraged at seeing his act at the New York State Fair’s sideshow in the ’80s. Bogdan went to court to have the sideshow banned, but Jordan fought back and won.

“How can she say I’m being taken advantage of?” Jordan reportedly said. “Hell, what does she want — for me to be on welfare?”

Irony had the last word in the situation. Soon after the judge ruled in Jordan’s favor, he died of kidney disease. In addition, sideshows were fading from the scene.

Jordan’s case could start roiling debates about earning money by showing one’s unusual body. Whatever one’s opinion of the exhibitions of yesteryear, the arc of change stands out for Black performers, from Joice Heth who, enslaved, lacked choices, to Jordan, who stood his ground in court. Even today, some Black performers’ distinctive bodies — Lizzo, and model and actress Tatiana Lee, from Coatesville, Pennsylvania, born with spina bifida, come to mind — are part of their persona.

In this fraught slice of Black history, performers’ unique bodies get the spotlight, but whether their anomalies were real or fake, what carried the show was their lively minds.

For more information, visit “The Uncle Junior Project, Celebrating the History of Black People in the American Circus,” online at unclejrproject.com.