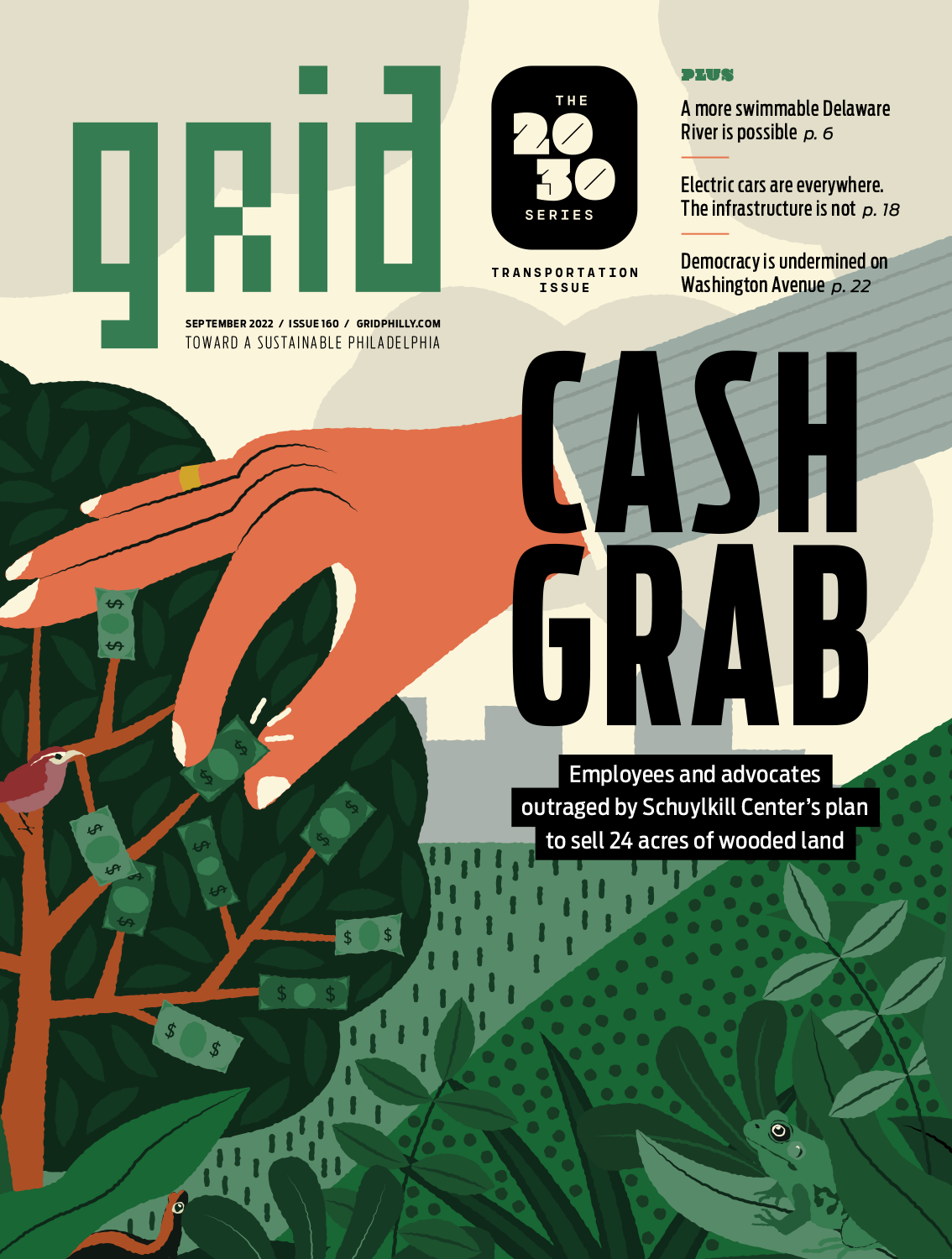

The canopy of red oaks, sugar maples and tulip trees provided a respite from the 94-degree heat on a July visit to the Boy Scout Tract. The cooling provided by the trees was a reminder of the importance of preserving tree canopy as global warming raises the temperatures in Philadelphia. The calls of blue jays, Carolina wrens, eastern towhees and red-eyed vireos provided a soundtrack along deer trails through the woods.

A plan by the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education to explore selling this 24-acre wooded parcel to developers has activated local open space activists and environmentalists who are preparing to fight to keep the sprawl that has consumed so much of the region from devouring the Boy Scout Tract as well.

The tract sits across Port Royal Avenue from the 340 acres of the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education’s grounds and across Eva Street from the Upper Roxborough Reservoir. Green Tree Run, one of Philadelphia’s few first-order streams (meaning it has no tributaries — rare in a city that has turned so many of its small waterways into storm sewers), begins its journey to the Schuylkill River in a steep ravine at the Boy Scout Tract, which earned its name by hosting camping Boy Scout troops from the 1950s to the ’80s. The Schuylkill Center acquired the land in 1987 through the will of Eleanor Houston Smith, whose family had earlier donated the land that in 1965 became the Schuylkill Valley Nature Center, later renamed the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education.

A walk along Port Royal Avenue in Upper Roxborough offers a tour of land preservation victories and losses, with the Boy Scout Tract, fate uncertain, in the middle. The Upper Roxborough Reservoir, targeted for development in the early 2000s, is now part of Philadelphia’s park system. Neighbors stroll on a path circling its basin, and its slopes bristle with newly planted trees.

Below the wooded Boy Scout Tract, the dusty outline of a small development called Port Royal Reserve provides a nightmare preview of what could happen if builders get their hands on the land, according to Jennie Love, owner of Love ’n Fresh Flowers. The sign at the 10-acre site announces six houses starting at $1,500,000. The developers cleared the trees on the site, graded the driveway, and, for the five years since then, development has mostly been paused, according to Love.

Stormwater runs off the property and down Port Royal Avenue, washing soil into the road and cutting a gully into the Schuylkill Center’s grounds near its wildlife clinic. “They have to bring in front-end loaders to clear the road when it rains,” Love says. She pointed out a pile of soil where the builders had laid a foundation for a model house and then torn it out. Love says clearing forest at what is now the Boy Scout Tract would only amplify the runoff problem while any planned houses are under construction, especially if the project hit similar delays.

The Schuylkill Center’s plans became public when, on March 9, an anonymous email address, “schylkllcntrlndsale@protonmail.com,” sent an email with the subject “Schuylkill Center Land Sale” to all staff at the organization with attached internal documents detailing plans to sell the Boy Scout Tract.

It is rarely good PR when a conservation group sells land to a developer.”

— Mike Weilbacher, Schuylkill Center executive director in a leaked memo

This was not the first time the Schuylkill Center had tried to sell the Boy Scout Tract. In 2004 a plan to sell to a developer who proposed to build more than 80 homes sparked a firestorm of community outrage and opposition. Mike Weilbacher, the Schuylkill Center’s executive director, described the reaction in an April 2021 memo (part of the leak) to the board: “The proposal … was somehow discovered by the neighborhood, which went predictably ballistic, as it is rarely good PR when a conservation group sells land to a developer. There was even picketing at our front gate.” The Schuylkill Center dropped the plans and the executive director at the time resigned.

Weilbacher drafted the April 2021 memo to the board to formally notify them that Daniel F. Gordon, a donor to the Schuylkill Center, had approached him with an offer to buy the Boy Scout Tract. Gordon sought to build two houses, one for his daughter and another for his wife and himself, as well as a barn to house his daughter’s horses.

According to the memo, Gordon had lost out on bidding for a 10-acre plot of land on Port Royal Avenue being sold by Jamie Wyper, a Roxborough open space activist and president of the Residents of Shawmont Valley Association, along with two other families who had acquired the initially forested parcel when it came on the market. They had hoped that they could limit the extent of development on the plot by choosing the ultimate developer. (This plan ultimately failed, according to Wyper. That 10-acre plot is now the aforementioned Port Royal Reserve.) Gordon then approached Weilbacher about the Boy Scout Tract, offering to buy it for about $1.5 million and including a conservation easement to limit development beyond the two houses and barn.

Conservation easements are a popular open space preservation tool for private lands. A restriction placed on the property’s deed limits development, so that even future owners are restricted in what they can build. Sometimes a third party pays for the easement, compensating the land owner for limiting development and the resulting loss in the land’s resale value. In other cases the land owner can use the value of the easement as a tax deduction.

In 2014 and 2015 the Schuylkill Center had applied to the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources for $1 million in funding to place a conservation easement on the Boy Scout Tract. They teamed up with Natural Lands, an organization that preserves open space in the Philadelphia area, often using conservation easements. The state turned them down both times, since $1 million could preserve much more land in rural areas where land is cheaper than in Philadelphia.

Weilbacher consulted with the board about Gordon’s offer, and as Weilbacher has said in meetings since, the board decided to convene a task force to more thoroughly consider if and how to sell the Boy Scout Tract. That task force decided to solicit additional offers to give the organization more options.

The leaked news of the possible land sale sparked opposition from much of the Schuylkill Center’s staff. Leadership held Zoom meetings on March 10 and 11 to present the plans to the staff and hear their concerns. Grid obtained audio from the two meetings.

Based on the recordings, staff members spoke up to address several points, including how the development of the Boy Scout Tract, however restricted by a conservation easement, would destroy wildlife habitat, for example that of the American toads whose spring migration is celebrated and protected by the Schuylkill Center’s Toad Detour program.

“We had an all-staff meeting, and I clearly disapproved of it,” said Eduardo Dueñas. Dueñas worked at the Schuylkill Center as the manager of school programs. He left recently after six years with the organization. He got his start there volunteering for Toad Detour. “That’s a way we connect the community. Based on that I would not agree on selling.”

Other staff were surprised to learn that the tract was even owned by the Schuylkill Center and said they would have offered programming ideas if given the opportunity. One staff person spoke up to ask who the board members involved were, since they had never met any board members in their time working at the center. The physical offices of the center leadership sit downstairs from the programming spaces at the organization’s main building. Programming staff complained of an upstairs/downstairs gulf between staff who worked with the public and leadership unaware of working conditions.

Several people expressed frustration with the lack of transparency about the process, which had been underway for a year, but which the staff only learned about through the email leak. Some staff at the meetings spoke up to say they were concerned that the sale violated the organization’s conservation mission. At the end of one of the calls, two staff members spoke up with concerns that the sale would damage the center’s reputation, which, they said, was already suffering among local birders and other naturalists.

The proposed sale of the Boy Scout Tract added to a list of staff complaints, such as low pay, that have fueled turmoil at the center. According to current and former staff at the center, about 20 people (at least a third of the workforce) left between October 2021 and June 2022, with each departure adding to the workload of those remaining.

At an April 28 evening Zoom discussion about forest restoration, Schuylkill Center staff essentially hijacked the meeting with questions about the sale, including about how alternatives to the sale might promote local land sovereignty, according to two attendees who spoke anonymously with Grid. The meeting, part of an educational series called Thursday Night L!ve, ended early, and was not posted to the center’s YouTube channel.

The March 9 all-staff email leak also reached Wyper and Rich Giordano, president of the Upper Roxborough Civic Association.

“When we got the anonymous email I reached out to some of the other civic [association] people, and I had a conversation with Mike Weilbacher, who largely confirmed overall what was in the email and said they were still working on whether they were going to issue an RFP [Request for Proposals],” Giordano says. After the conversation, the civic association leaders decided to give the Schuylkill Center the benefit of the doubt and wait for more information before alerting their members, many of whom had taken part in the resistance to the 2004 attempted sale of the land.

After three months they stopped waiting. In early June they convened a joint, closed meeting of the two civic associations to discuss the possibility of the land sale. After that initial meeting they invited the Schuylkill Center leadership to present the plans to issue the RFP, which resulted in a June 30 Zoom meeting at which Weilbacher and Schuylkill Center board of trustees members Joanne Dahme and John Carpenter presented the plans.

Weilbacher noted that the Boy Scout Tract was donated to the center with more flexibility than the original, core property of the center. He put the proposed sale into the context of past Schuylkill Center land sales, including the sale of what is now Manatawna Farms to the City in the 1980s. In 2006 the center sold a five-and-half-acre section of the Boy Scout Tract along Eva Street to a church.

The RFP includes language from Houston Smith’s will that makes clear the center is free to sell it. The land was “to be retained by the nature center, in whole or in part, for its stated purposes as its Trustees see fit, keeping in mind, but not being bound by my desire, that as much open space as feasible be preserved in the City of Philadelphia, but without restriction on the right of the said Trustees to sell or otherwise completely dispose of the premises … as they shall determine to be in the best interest of the Nature Center.”

Board members Carpenter and Dahme said that the Schuylkill Center would only consider proposals that included strong stormwater management plans. Half of the property is too steep to build on without a zoning variance, and the Schuylkill Center representatives said that they would require developers to include a conservation easement to prevent any future owners from seeking a variance and building on those hillsides.

Members of the civic associations submitted their questions (along with several comments opposing the sale) through the meeting’s chat.

Tom Landsmann, the president of the Roxborough Manayunk Conservancy, which works to conserve land in those neighborhoods, wrote, “What is the max number you would considers [sic].” Later in the chat Landsmann wrote, “I’d like to hear a rough conceptual number of how many houses that SCEE would consider.”

The Schuylkill Center representatives said that the organization had not made decisions about a revenue target or how many houses it would allow, though it would not consider proposals with the maximum allowable density.

They explained that they planned to use the revenue from the sale to fund capital expenses, for example improvements to the wildlife clinic and repairs to the visitor center.

Several attendees questioned why the Schuylkill Center would sell the land rather than use it for programming. Weilbacher said that the center had faced challenges using all of its core 340 acres for programming, and that in 50 years the Boy Scout Tract had not been used.

In actual fact the land is used. By wildlife.”

— Jamie Wyper, president of the Residents of Shawmont Valley Association

Wyper, president of the Residents of Shawmont Valley Association, responded; “In actual fact the land is used. By wildlife.”

In the chat, Michelle Havens, who had until March worked at the Schuylkill Center as office manager and gift shop manager, asked, “When was the last time you solicited feedback or recommendations from the Staff of the Schuylkill Center pertaining to the property and its usage for programs, since they would be the first and best resource for such questions?”

Weilbacher said that staff often volunteered programming ideas for the Schuylkill Center overall, but to his knowledge had never volunteered programming ideas for the tract.

Several comments asked for an in-person meeting in addition to the Zoom Q&A. Weilbacher and the civic association leaders said that there would be in-person meetings in the future to discuss the proposal, though they have yet to set a date.

Havens left the Schuylkill Center in the middle of March after working there for six and a half years. She questioned the need for the funds, given that the center’s endowment sits at about $5 million, according to their most recent annual IRS 990 report.

Both Wyper and Giordano made similar points in conversations with Grid, noting that plenty of organizations raise money through capital campaigns without resorting to selling off land.

“What we find disappointing is they went for the easy, low-hanging fruit here. The one way that is a way that violates their mission and reputation,” Wyper says.

“They’ve sold land several times before and wound up not necessarily in a better position than before they sold it,” Giordano says. “What you should do is really a development project, real fundraising rather than take a huge asset you have that’s important in its own right and sell it.”

Havens’ daughter, Kacey Plunkett, worked at the center from 2018 to May 2022 in a variety of education positions as she attended Chestnut Hill College, graduating in 2021 with a degree in environmental science. “It was so amazing to find a job that resonated with what I wanted to do with my degree, but everything started to fall apart,” she said. “At the beginning of 2022 it was so overwhelming because we had lost so many teachers.” Along with the low pay and the mounting workload, Plunkett cited poor leadership at the center, including from a board that had little contact with the staff of the organization, as a reason for her departure, which she documented in an email sent to all staff and to the board on May 20.

Selling land is not how you protect nature.”

— Kacey Plunkett, former Schuylkill Center employee

The Schuylkill Center declared 2022 to be its year of restoration, with a focus on habitat restoration at the center grounds, which Plunkett says clashes with the plans to sell the Boy Scout Tract. “It’s the year of restoration and they’re trying to sell a plot of land,” she says. “If I had known about the land, I would have taken preschoolers there … If we had known we would have been doing programs over there, showing people how we protect the land, how we protect nature. Selling land is not how you protect nature.”

Havens echoes Plunkett’s point about staff not being consulted for programming ideas at the Boy Scout Tract. “At no time was anything sent out to the employees asking for program proposals or usage proposals for that land,” Havens says.

Sandi Vincenti, who was the center’s director of early childhood education from 2017 to 2020, recalled discussions about using the Boy Scout Tract for camping at leadership meetings. “At a few senior staff meetings it was an agenda item.” She says they discussed using the site for camping by children enrolled in the center’s programs.

“Mike Weilbacher is a bald-faced liar,” says Andrew Kirkpatrick, who worked as the land stewardship manager for the center from 2016 to 2019. Like Vincenti, he told Grid that he had seen suggestions to use the tract as camping space in an old master plan, and that he had repeated to the center’s program managers the idea that the tract be used as a camping site for outside groups. “We had looked at that spot because it was out of the way, so groups could camp there and not be in the way of activity at the main site.” Kirkpatrick thinks the center’s leadership avoided programming on the tract to keep it open for a future sale. “They always kept that parcel separate so they could sell it off.”

Some Schuylkill Center staff support the sale. Sam Bucciarelli, the center’s land stewardship coordinator, says, “The Schuylkill Center currently does not have the resources to properly care for the parcel, and I am in support of a conservation-minded sale including a conservation easement.”

During the June 30 civic association call the center representatives said that the organization is not committed to selling the Boy Scout Tract and could very well decide in the end that no offer is worth it. Giordano suspects, however, that the money will be hard to turn down once they are confronted with concrete offers. “My concern is when you put something out into the world like this, stuff comes back to you that becomes tantalizing. It has a big dollar amount attached to it, and you are induced to do something you might not have done before you had that boulder rolling down the hill.”

Weilbacher declined to be interviewed for this piece, directing questions to Amy Krauss, the center’s director of communications. Grid asked why the center hasn’t set a target for the sale price or limits on the development they would approve. Krauss responded by email: “The Center’s Board of Trustees will evaluate the proposals based on multiple criteria: price offered to the Center; percentage of the Tract to be conserved; how the proposal addresses environmental concerns including, but not limited to, stormwater, soil disturbance and tree removal; suitability to the neighborhood; the developer’s track record and credibility; and any additional criteria determined by the trustees.”

Much of the discussion at the civic association meeting revolved around what the development of the Boy Scout Tract would mean for overall open space preservation in the neighborhood. The Schuylkill Center staff repeatedly assured the attendees that City water and sewer service would not be extended down Port Royal Avenue. Currently the houses on that hillside draw their water from wells and dispose of sewage through septic systems. These systems limit housing density, so the concern is that extended water and sewer lines would open up the rest of the neighborhood to denser development.

While this could be seen as a NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) response by people privileged to own homes surrounded by open land, Giordano frames it as a defense of what in Philadelphia is an endangered landscape. One hundred years ago much of the city was still rural, particularly in the Northeast and Northwest. Today all those fields, forests and pastures have been developed. “Port Royal Avenue is literally a survivor of 19th-century agricultural Philadelphia,” he says.

“I think it’s hard for people to appreciate,” says Giordano, who, along with Wyper, led efforts to preserve the Upper Roxborough Reservoir and convert it to public park space. “We do tours at the reservoir. When I stand at the entrance I point at the Schuylkill Center and Manatawna Farms and down Shawmont Valley to say the amount of green is amazing to be inside the sixth largest city in the United States. It’s not little chunks. It’s almost continuous. This is important for the quality of life, for wildlife habitat.”

“In 2002 we had this area, this neighborhood, established as a historic district, the Upper Roxborough Historic District,” Wyper says. “It encompasses 1,500 acres of largely open space. It extends into Whitemarsh Township. It includes Manatawna Farms. That doesn’t give us much protection, but it gives us an identity.”

The Schuylkill Center released its Request for Proposals on July 11, with submissions due by September 23. The Schuylkill Center is a private organization contemplating a sale that wouldn’t require a zoning variance, which gives the public little leverage over the outcome. Nonetheless, the organization “depends on donations and grants, and their public face should be important to them,” Giordano says. “It’s a public face dependent on people who take these issues to heart in a serious way and wouldn’t look kindly on an organization that they think is betraying them.”

Giordano says he hopes the dispute doesn’t escalate as it did in 2004. “[It] was awful for them. It was awful for us, too,” he says. “Right from the beginning, my goal is let’s not go that route again… I hope at some point we have an offramp. I hope it doesn’t degenerate into some kind of bitterness.”

Opposition to the possible sale of the tract has manifested in a website (savetheboyscouttract.com), a Facebook group and an Instagram account (@savetheboyscouttractscee). Neighbors have begun putting up yard signs reading “No Land Sale! Schuylkill Center Must Save Land.”

“When I heard about the possible sale of the [tract], it felt like a violation of the community’s faith in the Schuylkill Center. Environmental centers at their very core are meant to protect the environment, not aid in the sale of it to developers,” says Stephanie Hammerman, who started the social media accounts along with other advocates. “The people involved in these groups are local community members and are all huge advocates of the Schuylkill Center and the environment, but are deeply concerned about the current direction it’s going in. They use and care for the space regularly and want it to remain in its current state where wildlife and human life can continue to enjoy it.”

Jennie Love farms flowers on four-and-a-half acres of what was once part of a farm that Wyper and other neighbors successfully preserved as open space. “We were able to put 21 acres into conservation easements,” Wyper says. “It’s a remarkable little agrarian setting.”

Love, though, is concerned that conservation easements might not be strong enough to protect the Boy Scout Tract once the property is sold by the Schuylkill Center, which, as a nonprofit organization, is not subject to local property taxes, to a private owner, who is. “I know the economic pressures that will come down on the owners of that land,” she says. She thinks a wealthy owner could clear more land than is permitted by an easement and choose to fight it out in court. Even if they lose the suit, the damage will be done. Love’s land is also protected by a conservation easement, but the City initially assessed the land’s value at what it would be worth without an easement. Love says that she had to fight to have her taxes reduced to reflect the value of the land minus the easement. “The point is once the Boy Scout Tract comes out from a nonprofit entity, I don’t care who says they’re putting it under conservation easements. I can say from experience it will be a nonstop battle from there on out to safeguard it.”

Love pointed out that the Boy Scout Tract’s location, directly across Port Royal from the core grounds of the Schuylkill Center and across Eva from the Upper Roxborough Reservoir, situates it well for public use. It is easy to imagine a trail running through it, knitting it together with those other publicly-accessible green spaces and inviting neighbors in.

“We need more of this space,” she says. “Why not keep it for citizens to use rather than putting it into development? There’s so much value to this land, value to wildlife, value to the community. This is just lazy leadership.”

Funny now they can sell it. When Greenwoods school wanted to build a school there (which was for enviormental education which would have been low impact green building they refused the school.

Awesome job, Bernard. Thanks for your work.

Excellent summation of the situation and players. Thank you! I’m a local resident hoping we can find a way to preserve these woodlands. The tract’s location next to other preserved land in Northwest Philly adds to the importance of keeping the land undeveloped. This is irreplaceable open space.

My experience from 20 years of dealing with builders /property developers /and landowners has been with enough will power and resources ie money, they can have any legal protections overturned in court including deed restrictions. The protection of the land also becomes dependent on the disposition and fortunes of future civic and conservation groups. Those groups may not have the necessary resources to hire competent legal council or the ability to make multiple court appearances over a period of years. There are numerous neighborhood conservation overlays in force in the 21st ward and developers have managed to overturn certain protective aspects of those NCOs in court via their high powered lawyers. I foresee the same fate for whatever protective mechanisms that are included in future sales of SCEE’s land. The real elephant in the room is the SCEE board of directors (whose mission is to conserve, protect and nurture their deeded land) who have seriously considered the sale of their land for profit. There are great challenges keeping a nonprofit solvent especially in today’s uneven economic landscape I sincerely hope the S3CEE board and the community can explore and implement more dynamic methods for staying solvent and continuing their mission of land conservation and community education.

Well said, David!

If this story irks you, please sign the petition! https://www.savetheboyscouttract.com/petition/

Thanks for the link; I came here to ask what we can do. This is outrageous. I don’t care about what the courts or other human beings will ultimately decide to do regarding the lives of the nature already living there.

Excellent reporting, Bernard! THANKS

What other “nature center” has had this many public protests under one executive director? First their groundskeeper who filed an EEOC lawsuit against them, then all 60 of the wildlife clinic volunteers who quit when the week resources had off the clinic was unfairly fired, now this disgraceful land sale. Something stinks here and i think i know who it is.

Sorry, typos. That should say, “then all 60 of the wildlife clinic volunteers who quit when the respected head ofthe clinic was unfairly fired, “

Readers might be interested to see what weilbacher had to say when another organization wanted to sell off green space for development in HIS main line neighborhood. Obviously, he was strongly against it, enough to write an op ed!

https://www.mainlinemedianews.com/2013/03/13/an-open-letter-to-archbishop-about-st-charles-borromeo/

Forgot to add… this excoriating reply to weilbacher is priceless

https://www.mainlinemedianews.com/2013/03/24/rosemary-mcdonough-an-open-letter-to-mike-weilbacher-on-st-charles-seminary/

The SCEE mission statement makes it clear:

“We engage with our forests and fields to foster appreciation, deepen understanding, and encourage stewardship of the environment.”

If they sell their land to developers, they have failed in their mission. The entire board and Weilbacher need to be replaced; if they had any integrity or dignity they’d step down without prompting.

If the duplicity and terrible treatment of the employees weren’t enough, the fact they need to sell land to raise funds is a clear demonstration of how utterly useless they all are at their jobs. Regardless of whether it may be as a result of misfeasence or malfeasence, they need to go.

Even better, they dedicated 2022 as a ” Year of Restoration” ” a year dedicated to restoring habitats, our connection to the land, our communities, and our relationship to nature.”. The hypocrisy would be comical if it wasn’t so sad

Excellent reporting! I’m a Parisian-New Yorker who ended up in Philly because of her husband’s job. It took me a while to feel at home here, and it finally came down to two things: the grit of the people (those long voting lines during a pandemic filled me with admiration) and the other thing that made me fall in love with Philadelphia was the endless vistas of green over Fairmount Park and in Roxborough. Such a sight in such a large city is utterly remarkable and awe-inspiring— much more so than the Notre Dame Cathedral or New York City’s iconic skyline. What we have here is a priceless heritage for future generations, especially as they fight the warming of their climate. During the last two heat waves, I’d walk my dog in the evenings and marvel at how cool and green the forest remained despite the scorching temperatures. Cutting down the Boy Scout Parcel is madness. Old growth trees can lower a city’s temperatures by ten degrees and even clean pollutants from the air; the U.N.’s Biodiversity page has recently posted that urban trees are of the utmost importance as our planet heats and populations move to cities. We need to preserve those marvelous trees as if each were the Notre Dame Cathedral— and mind you that was rebuilt after a recent fire. Those trees can never be replaced.

“Such a sight in such a large city is utterly remarkable and awe-inspiring— much more so than the Notre Dame Cathedral or New York City’s iconic skyline. What we have here is a priceless heritage for future generations, especially as they fight the warming of their climate. During the last two heat waves, I’d walk my dog in the evenings and marvel at how cool and green the forest remained despite the scorching temperatures. “

PUT THIS ON THE PETITION WEBSITE – or hang it in the Louvre. 🤌🏽

Them raising money as an alternative, in order to not sell and develop the land, is like negotiating with terrorists. “Give us money to NOT do the wrong thing”. How about just not doing the wrong thing? Mike Weilbacher would lie even if the truth would serve him better.

My home overlooks the Shawmont Valley. I emailed the Schuylkill Center and this was their reply. It feels they have already made their decision on what they plan to do.

We wrote-

To Whom it May Concern,

I live on Gettysburg avenue right across the creek from Boy Scout tract. I purchased my house for the beauty of this pristine forested landscape and the uniqueness it has. Little did I know just how rare it actually is.

Since living here I’ve had to buy books to identify the birds that come to the feeders (5 different woodpeckers.

Piliated/Flicker/Harry:Downy/Red Bellied, Indigo bunting, Towhee, Evening Grosbeak, Rose Breasted Grosbeak, Winter Wrens nest in bird houses, Wood Thrush, Ruby Throated & Rufous Hummingbirds, Baltimore Orioles) most of which also are accompanied with adolescents. They do not nest on the property but must nearby, presumably in Boy Scout tract.

Skunks roam freely in the spring across the lawn. Massive deer graze all year round and rut in autumn. Occasionally rare piebald deer. Never have I heard fox calls or flying squirrels until living here. Their are toads literally everywhere, they crawl right out of the ground like a seed sprout. Unexpected crawfish in the creek along with salamanders.

The wildlife here is magnificent but also very delicate and fragile. The forest & trees alone are wonderful to look at. All this wildlife needs a place to live and Philadelphia has so few left to offer them. They aren’t all just backyard animals, some have a shy temperament and need a place of refuge.

I know you haven’t been able to utilize the land in almost 80 years but you really should at the most consider developing minimally invasive trails. Walking on that side of the creek is amazing and almost like a hiking trip back in time. The has already been one development since I’ve lived here on Port Royal that leaves a noticeable scar the landscape. It would be a shame to loose more of this profound ecosystem when there is obviously so much to learn from taking a step back and letting nature be natural.

If there is anything I can do help you to continue to conserve this land please contact me. To see it threatened is heart breaking.

Sincerely,

Azura Ahmad

They responded-

Azura,

how beautifully written and yes, there are so many critters teaming in our woods. It’s great to see a neighbor appreciate the beauty of our property. We have written into the proposal very specific instructions including a permanent easement to preserve at least half of the property while allowing for the continued migration of toads. Hopefully, any changes will respect the habitat to the greatest degree possible.

Amy Krauss

As a former employee who worked there before and during Weilbacher this is extremely disappointing, but not surprising. Actions speak louder than words and with that it has been clear that education and conservation is not the priority.