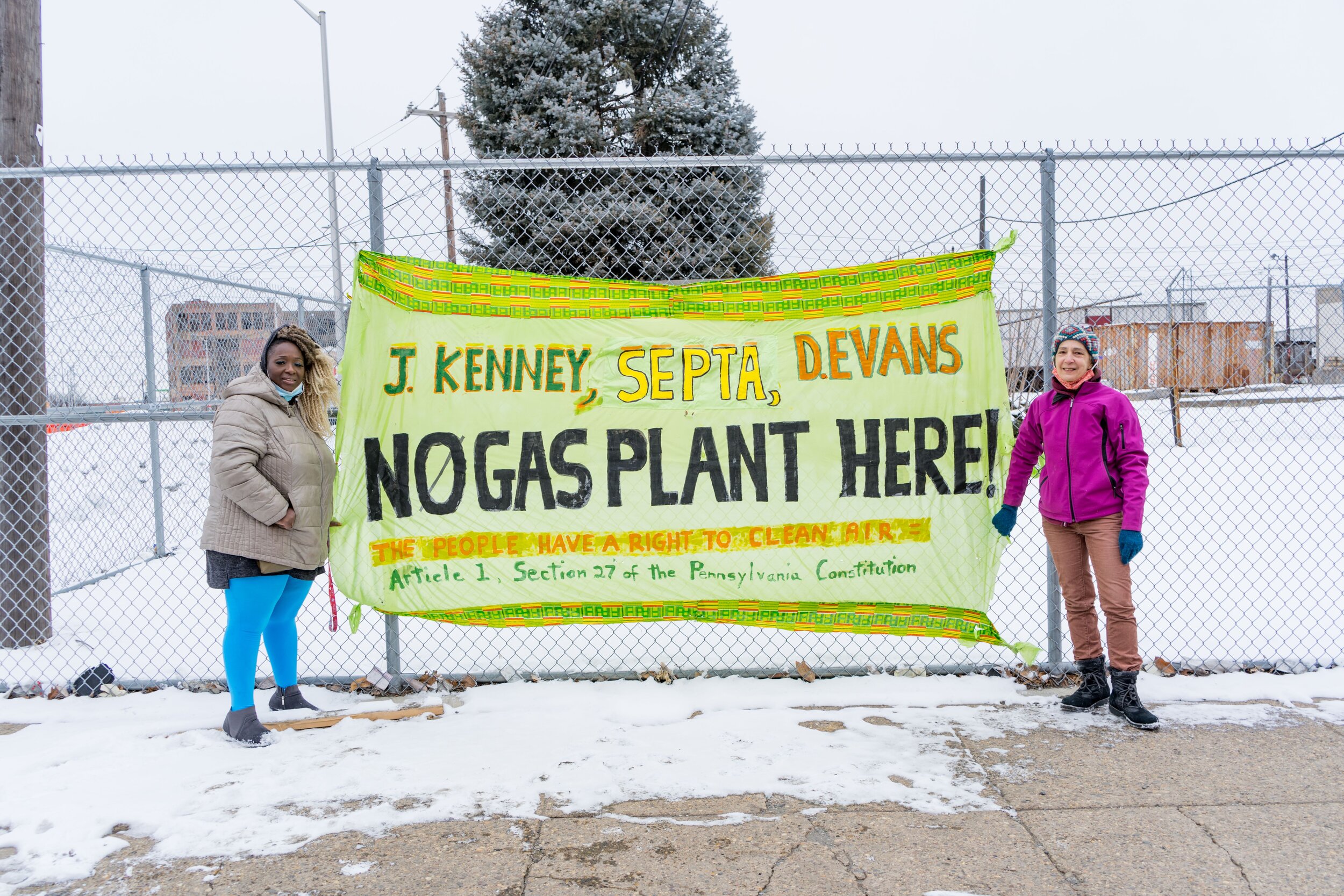

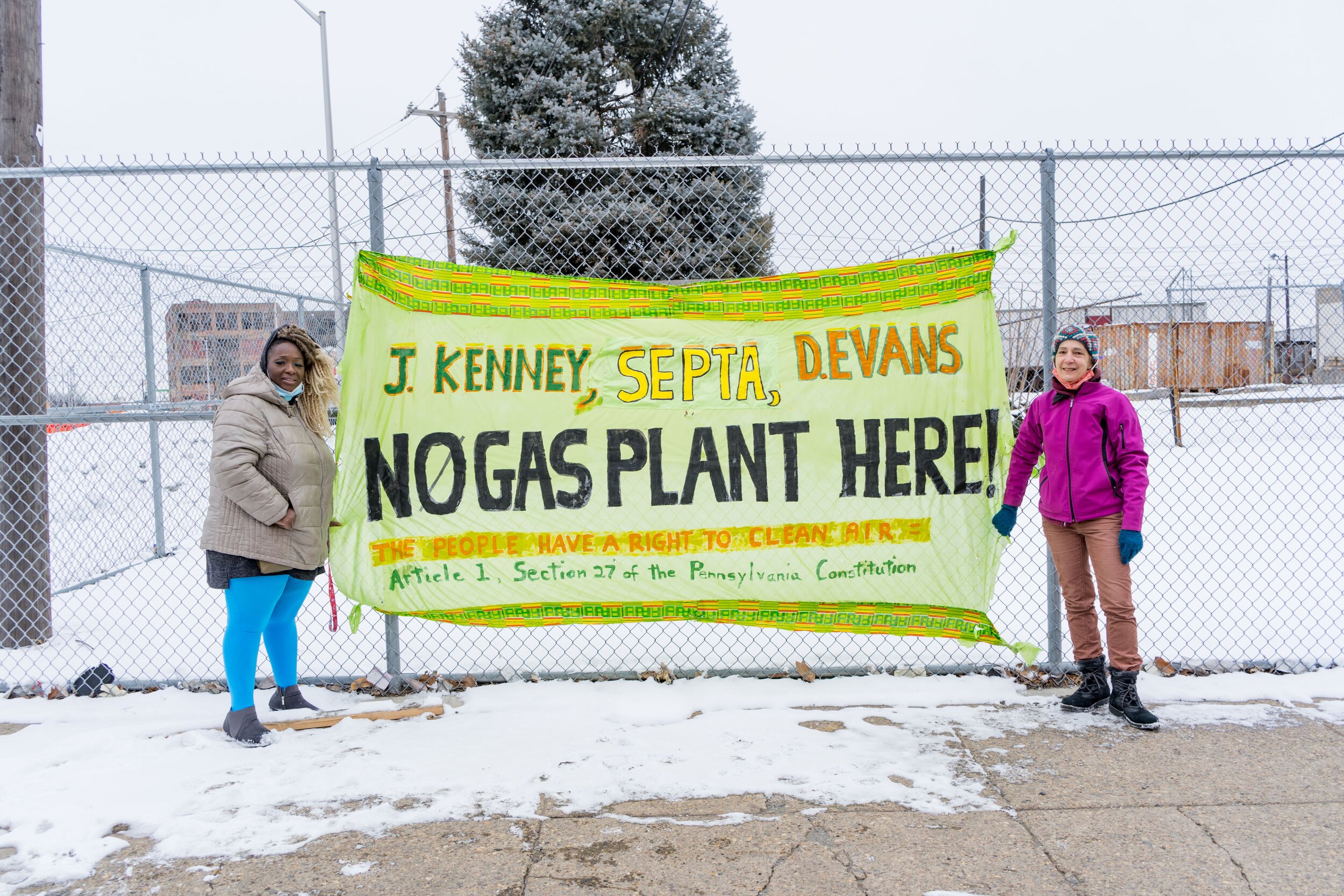

In November 2019 the City of Philadelphia approved SEPTA’s request to operate a natural gas–burning power plant in the Nicetown neighborhood of North Philadelphia.

This approval marked a defeat for the neighbors opposing the plant, who are now preparing for the next phase in the struggle: taking oversight of the new plant’s emissions into their own hands. In doing so they are joining the growing ranks of Philadelphians monitoring their own air quality and revealing the invisible injustice of pollution.

According to Nikki Bagby, a member of Neighbors Against the Gas Plants (NAGP), the plant will join a long list of pollution sources plaguing Nicetown and surrounding neighborhoods, including SEPTA’s nearby Midvale Bus Depot, as well as the thousands of cars and trucks spewing exhaust on the Roosevelt Expressway and other arterial roads running through the neighborhood.

A 2019 Department of Public Health report ranked Nicetown-Tioga 45th out of 46 Philadelphia neighborhoods in overall health outcomes. The prevalence of health conditions exacerbated by air pollution, such as asthma and cardiovascular illnesses, are all higher than city averages.

“The idea is that we can show that this area we live in is bombarded by all these different pollutants.”

— Thakiyah Ahmad-Yankowy, NAGP member

With the gas plant now constructed and approved to operate, NAGP is planning to measure the air quality impact of the plant, starting by documenting the already-high levels of neighborhood air pollution.

“The idea is that we can show that this area we live in is bombarded by all these different pollutants,” says Thakiyah Ahmad-Yankowy, a member of NAGP who lives in Germantown, just across Fernhill Park from the site of the gas plant. “You would think that living next to an expressway and a bus depot you wouldn’t need to do that.”

According to Lynn Robinson, the director of NAGP, the group plans to use stationary air quality monitors on neighbors’ houses as well as mobile monitors. NAGP members express frustration that they have to take on monitoring and mitigation themselves. “It’s something that’s taking up our time and energy and resources, and we shouldn’t have to do this,” says Robinson.

The Department of Public Health’s Air Management Services (AMS) operates 11 air quality monitoring stations as part of an EPA network. AMS also recently ran a pilot study called the Air Quality Survey, with 50 monitoring sites, from 2016 to 2018. “It’s a big project to make sure that each community breathes the cleanest air, and, if not, we go to the policymakers and say we need to do something,” says AMS Director Dr. Kassahun Sellassie. For example, if a station detected high levels of emissions from diesel engines, AMS could recommend that SEPTA run electric buses on routes through that neighborhood.

However, NAGP’s Robinson noted several reasons the city’s air management team is not meeting her group’s demands, including that AMS has not yet published the results from the pilot; the 50 sites are concentrated in Center City; and the sampling equipment, which rotates among the sites at two-week intervals, does not yield the continuous monitoring NAGP is looking for.

Off-the-shelf air quality monitoring technology is helping to fill in the local gaps. For example, PurpleAir brand monitors measure particulate matter and feed the information to a publicly viewable online map.

Christina Rosan has a PurpleAir monitor on the porch of her West Philly house and would like to see more of them monitoring local air quality, particularly in the neighborhoods around Temple University, where she works as an associate professor of geography and urban studies. Along with graduate student Naida Elena Montes and Russell Zerbo, advocate with the Clean Air Council, Rosan has been reaching out to North Philly residents to document community challenges.

“We’ve been meeting every Friday with the RCOs [registered community organizations] to talk about the collective challenges they’re having. Focusing on disinvestment, gentrification and environmental

challenges,” Rosan says.

Although large polluters like power plants and chemical facilities grab headlines, they have permits allowing them to pollute, Zerbo says. Pollution measured by neighbors doesn’t lead to enforcement by regulators as long as the pollution stays within the permitted levels. However, neighbors can get authorities to crack down on smaller sources that can still be significant on a local scale.

For example, gentrification, a leading concern for those living around Temple’s campus, is driving an increase of rowhouse demolitions, which often kick up clouds of dust.

“Any particulate in the air will get into your respiratory system and cause irritation, asthma and other health issues,” says Zerbo. “When you think of what that dust actually is, it gets infinitely more frightening. We’re talking about lead, asbestos and other substances.”

And unlike most air pollution, construction dust is easy to spot with the naked eye.

“I looked down and saw this red dust on the inside of the window sill. Then I started looking around the bedroom and saw more,” says Jacqueline Wiggins. A rowhouse demolition in November around the corner from her North Philly house had kicked up a cloud of dust that settled over her block. Wiggins immediately contacted the AMS as well as a long list of city councilmembers and other city officials. Although the demolition was already completed, she wanted to do her part to improve accountability for construction violations. “The hope is that you get into the next pile of complaints,” she says. “People in this town are not respected.”

“I have a resident-based perspective,” says Montes, who lives just south of Temple University Hospital. She pointed out that many of the pollution sources in the neighborhood, such as automotive shops, employ her neighbors, complicating an enforcement strategy. “It’s a very … weird position to be in. As a resident I don’t want to live in these conditions. But it is also their livelihood.”

Montes, who studies geography and urban studies, is eager to get a monitor on her house to at least make the pollution problem visible. She is not alone in seeking to bring air pollution to light across the city as part of an environmental justice strategy.

Craig Johnson, of the design firm Interpret Green, has worked with schools in West and North Philadelphia to set up air quality monitoring stations as part of a project called Sensing Climate Change. Along with weather monitoring equipment that can provide information on the local impacts of climate change, the stations can show what’s actually in the air the students breathe.

“Our Sensing Climate Change project has received enthusiastic support from the School District of Philadelphia’s GreenFutures Office and their [School] Greenscapes initiatives,” says Johnson, adding he is looking for additional schools as well as religious congregations that would be interested in hosting stations.

Most air pollution is invisible, but several advocates pointed to its very real impact on the lives of people of color. According to the Department of Public Health’s 2017 Community Health Assessment, “Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children have rates of hospitalization for asthma 5 to 7 times that of non-Hispanic white children.”

As Ahmad-Yankowy, whose youngest child has asthma, says, “We realize there is great racial injustice that we live with every day.”

“Environmental racism is a lot harder for people to catch a recording of,” Ahmad-Yankowy continues. “But people have to know it exists.”

Is this really a “proposed” site. I thought the plant was complete and now operational.

Am I misinformed?

It is complete now and operating- or -something is coming out of the smoke stacks anyway. We need to shut it down now.