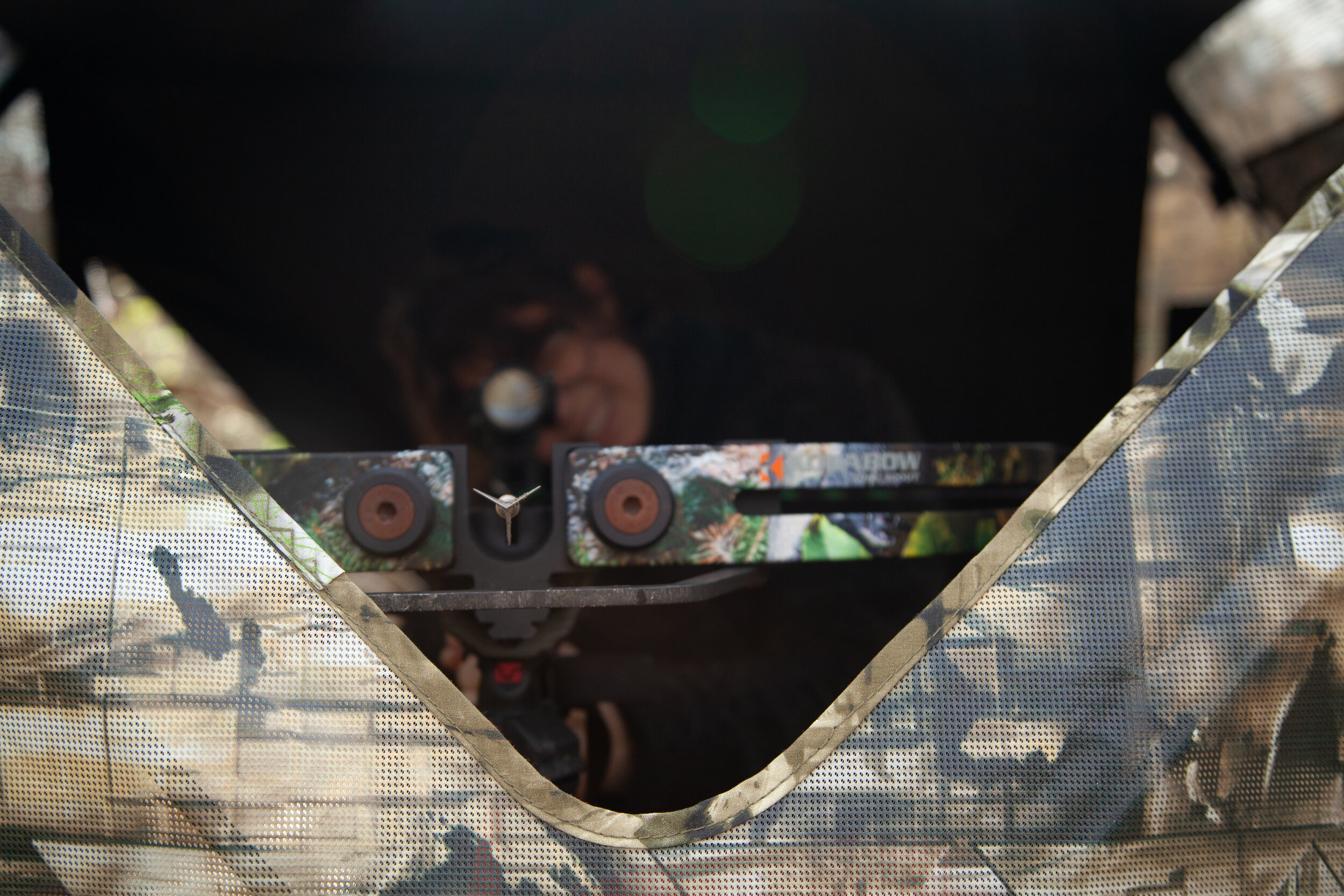

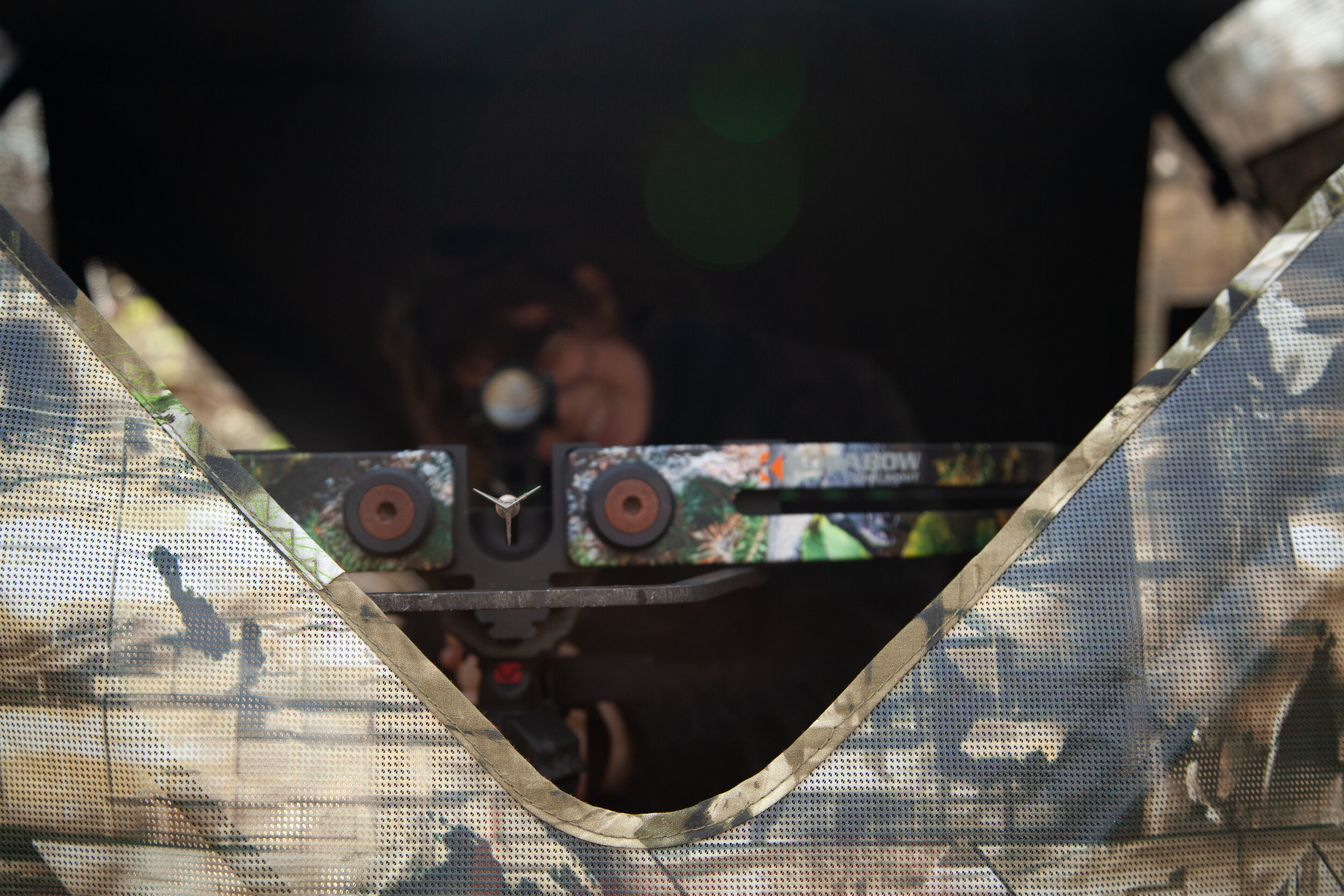

The sun is barely above the horizon when we creep between the trees and quietly enter the blind. I load the arrow into the crossbow, looking eagerly out of the mesh window. It’s the first day of my first hunt. I’ve never killed anything and I’m not sure that I can.

“I like this spot,” says my mentor, Derek Stoner, a hunter outreach coordinator with the Pennsylvania Game Commission. “A big buck was killed here last year.”

As an environmentalist, I’ve travelled the world filming with researchers working to protect animals. I’ve always considered hunting in the name of conservation to be a ruse made up by gun-loving sportsmen. Fifteen years ago, I never would have guessed I’d swap a camera for a crossbow, but over years I’ve learned that environmentalism is full of contradictions when you look at the big picture.

It is the weekend of Nov 19-21, the weekend of the second annual mentored deer hunt at John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge, just a few miles from the Philadelphia International Airport. The 993 acres of marshes and forests is a popular place for birdwatchers, but it’s also home to a lot of deer.

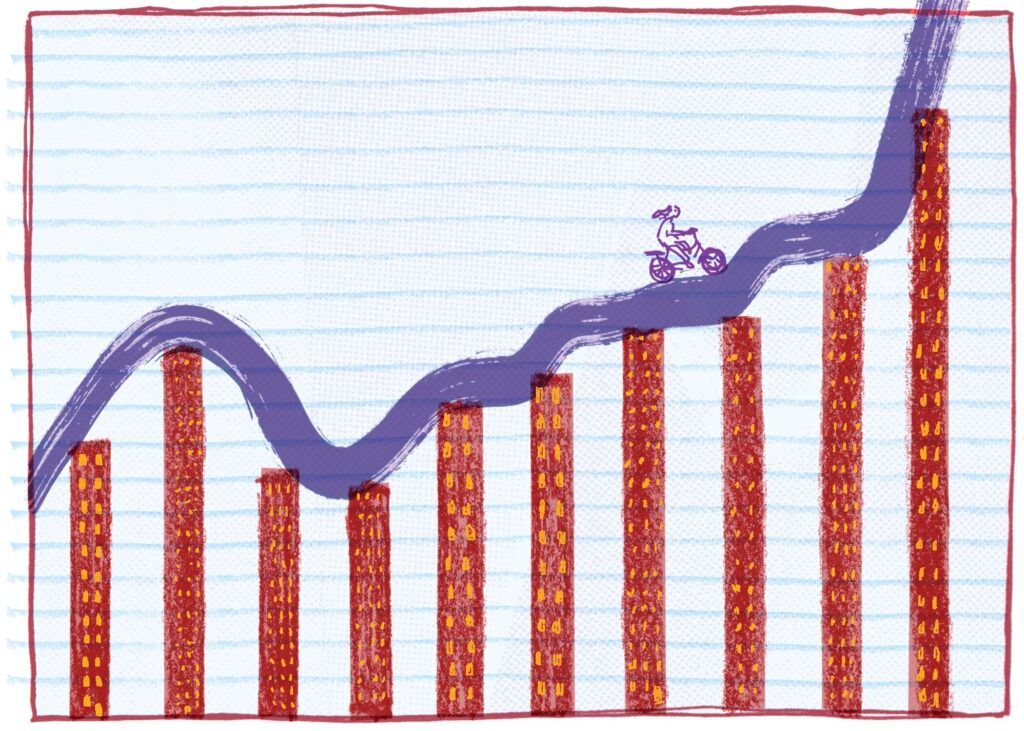

A balanced ecosystem can sustain 8-10 deer per square mile but the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that the Philadelphia area has a population closer to 30-40 deer per square mile, which poses safety risks for people.

In 2017-2018 Pennsylvania had 141,777 deer-related vehicular accidents, the highest in the country – over 50,000 more than the next state on the list. In past deer count surveys, the population at John Heinz was higher than the forest could support and needed to be managed. Last year, the refuge used this to further its mission to educate residents about conservation through outdoor recreation by starting the mentored bow hunting program.

Although most environmentalists would prefer that nature be left alone, Pennsylvania’s deer population has been long affected by people. Severe overhunting obliterated the deer population and in 1895 the game commission relocated new herds from the Midwest. While predator populations were also decimated, they were not reintroduced. Some, like coyotes, are still around in more limited numbers, but, mountain lions and wolves are thought to have been extinct in PA since the late 1800s. With few predators left to feed on young fawns, a balanced deer population can quickly outgrow its patch of forest, like it has at John Heinz.

Three hours in the blind and it would be cold enough to see our breath if not for our COVID-19 masks. “I’m going to try some calling,” Stoner says, pulling out a ribbed tube.

Baiting deer isn’t permitted at John Heinz but using calls is allowed. Stoner trumpets into the tube mimicking the sound of a male deer to draw it to us. In order to legally shoot a deer, it has to be the right deer. I have a deer tag for one buck with three points on its antler. John Heinz has also supplied me with two doe tags, which are more regulated because the females control the herd population.

“The only way you’re going to reduce the population is if you kill the females, not the males,” says Garrett White, biological science technician at John Heinz. “The male won’t produce any more offspring, but the females will produce two a year after a couple of years. So that’s where your population control comes in.”

To ethically shoot a deer, my aim has to be spot on, killing the deer quickly with a shot to the heart. To do that, I need the deer to come within my 30-yard range—an area the size of my rowhome backyard—directly in front of my bow, no longer moving and without obstacles in the way.

The sound of Stoner’s calls puts me on edge and sends my adrenaline rushing. I sit silently and alert, twitching at the sound of every falling leaf, crashing to the forest floor. I am sure that any second now a buck is going to wander in, perfectly situated in the opening between the wall of feathery phragmites and my crossbow. I imagine the target right behind his shoulders and how easy it is to pull the trigger sending the arrow into his heart. Then I picture every deer I’ve encountered on hikes, startled and still, staring at me with their big eyes. On one hand I’m ready to switch the safety to fire and take the shot but on the other I worry I might freeze, like the stereotypical deer in headlights, unable to kill such a peaceful animal.

Outside the refuge gates are protesters’ signs. They say the refuge should be a safe place for all wildlife. I don’t disagree but I know after years of working in conservation as a filmmaker that this is short-sighted. A single deer eats about 5 pounds of plant matter a day. Too many deer can decimate a lot of undergrowth in the form of young saplings and native herbaceous species. Forests cannot regenerate without saplings that eventually grow into strong, old trees and clearing out native plants gives introduced species a leg up.

“At some point all trees die,” says White. “So, you do need something else growing up behind that to sustain a habitat. A high deer population will eat all the trees that will be replacing the ones that we currently have there.”

Letting nature take its course with the deer also leaves other wildlife at a disadvantage. Ground nesting birds have no chance of hiding their young without the cover of undergrowth. With deer eating all the flowers there’s little left for native pollinators to forage. Eventually without new saplings to take the place of dying trees the forest can die completely. Whether it’s novice deer hunters or a sharpshooter team from Animal Plant Health Inspection Service, to manage pockets of forests, deer have to be managed.

On top of maintaining the health of the forest, wild game is one of the most sustainable protein options people have. Commercial livestock production accounts for 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions and is a big polluter of our waterways and air. In some places, particularly the Amazon rainforest, it’s driving 80 percent of deforestation which impacts the native species there, causing extinction. Processing the billions of pounds of meat annually in the U.S. is also a public health issue. Earlier this year, meat processing plants were hot spots for COVID-19, with 239 facilities reporting more than 16,000 cases and 86 deaths, raising questions about the safety of meat production.

For those who choose to eat meat, doing so sustainably and humanely can be expensive. One large deer can pack your freezer with up to 153 pounds of meat, according to the game commission, which is well over a year’s worth using the World Cancer Research Fund’s guidelines of around a pound of red meat a week. Based on the deer I’ve seen around the refuge, I’m only expecting to take home 30-40 pounds on my hunt, still enough for much of the year.

Scanning the woods, a doe silently appears.

“There’s a deer,” I whisper excitedly. “But she’s too far.”

Stoner and I watch her walk on, probably heading to water after feeding. In three days, from predawn to evening, I saw a total of nine deer, three of which were from the blind but not within shooting range. I’m still unsure if I have it in me to look a deer in the eyes and pull the trigger, but I know that if I do, my gratitude for the life I take to feed myself will be immense.

Until then, I discover that sitting quietly listening to the forest for hours isn’t wasted time, a sentiment I share with White.

“The stress relief for me that comes from sitting in the woods and listening to nature—that’s theoretically priceless for my overall health,” White says. “And who cares if I didn’t get a deer.”