On May 25, Christian Cooper, birder and member of the New York City Audubon Society’s Board of Directors, was birding in Central Park. He asked Amy Cooper (no relation) to follow the park rules by putting her dog on a leash and then recorded what happened next: Amy, who is white, called 911 to report that an “African American man” was “threatening” her and her dog. It served as an example of how white people can wield a call to the police as a weapon against Black people. Occurring on the same day that George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer, it made clear that simply birding while Black could be lethal.

“It doesn’t matter what education or job you have,” wrote Melody Cooper, Christian’s sister, in a May 26 tweet, “every Black man is vulnerable.”

Keith Russell, program manager for Urban Conservation with Audubon PA says he was shaken up by the Central Park encounter.

“It was scary,” says Russell. “Those … are dynamics I haven’t experienced while birding, but they’re dynamics I’m familiar with, and you know your life flashes before your eyes because once a door is opened, you don’t know how bad it could be.”

Social media users soon came up with a response: a campaign called #BlackBirders Week.

“Black Birders Week is the product of a group chat,” explains Brianna Amingwa. Amingwa is a supervisory park ranger with the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum, #BlackBirdersWeek organizer and @Ranger_Bri on Twitter.

“The [#BlackAFinSTEM collective] is all Black people across the country, many of them young, early-career or graduate students, all in STEM. There’s a big contingent of birders and herpers in there, so when the incident with Christian Cooper happened we were talking about it and our frustrations,” she says. “It also put a spotlight on birding, and that’s when the idea happened.”

As the #BlackAFinSTEM community discussed how a #BlackBirdersWeek could respond to the incident in Central Park, three themes emerged, Amingwa says. The first was visibility and representation “so that Black people do have a space in this area,” Amingwa explains. “This is a thing we can do and should do.”

Secondly, they focused on “creating a dialogue within the birding community as well, to make it clear about what the experience is as a Black birder for people who usually don’t have to think about that sort of thing,” Amingwa adds. Lastly, they aimed to highlight diversity in the birding community and highlight the value of diversity generally.

“Diversity is valuable in any ecosystem,” says Amingwa.

On May 31, the #BlackInNature posts poured in on social media, kicking off #BlackBirdersWeek. Pictures showed Black people birding, fishing, hiking and enjoying the outdoors. Amingwa posted a photo of herself in middle school, riding a horse with a program that she says ignited her love for nature.

#BlackBirdersWeek followed #BlackInNature with a #PostABird challenge on June 1, #AskABlackBirder Q&A on June 2, #BirdingWhileBlack live stream discussions on June 4 and #BlackWomenWhoBird posts on June 5.

“When the national conversation was on the Black experience, #BlackBirdersWeek made it clear that it’s not just about trauma, it’s about joy, resilience, pride, strength and style,” Tykee James, government affairs coordinator with the National Audubon Society and a #BlackBirdersWeek organizer, wrote by email.

Russell, who tuned into a live stream discussion on Facebook moderated by James, says he was happy to connect virtually with other Black birders across the country.

“It’s good to see the number of Black people who are into birding is increasing,” he says.

Russell also emphasizes the broader value of seeing the birders featured during #BlackBirdersWeek.

“If you think there are no Black birders out there, you might not even try [it],” he says, citing his own experience as a teenager in the early 1970s meeting James Carroll, a Black birder and naturalist, who worked at the National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum (now named after Senator John Heinz).

Amingwa agrees.

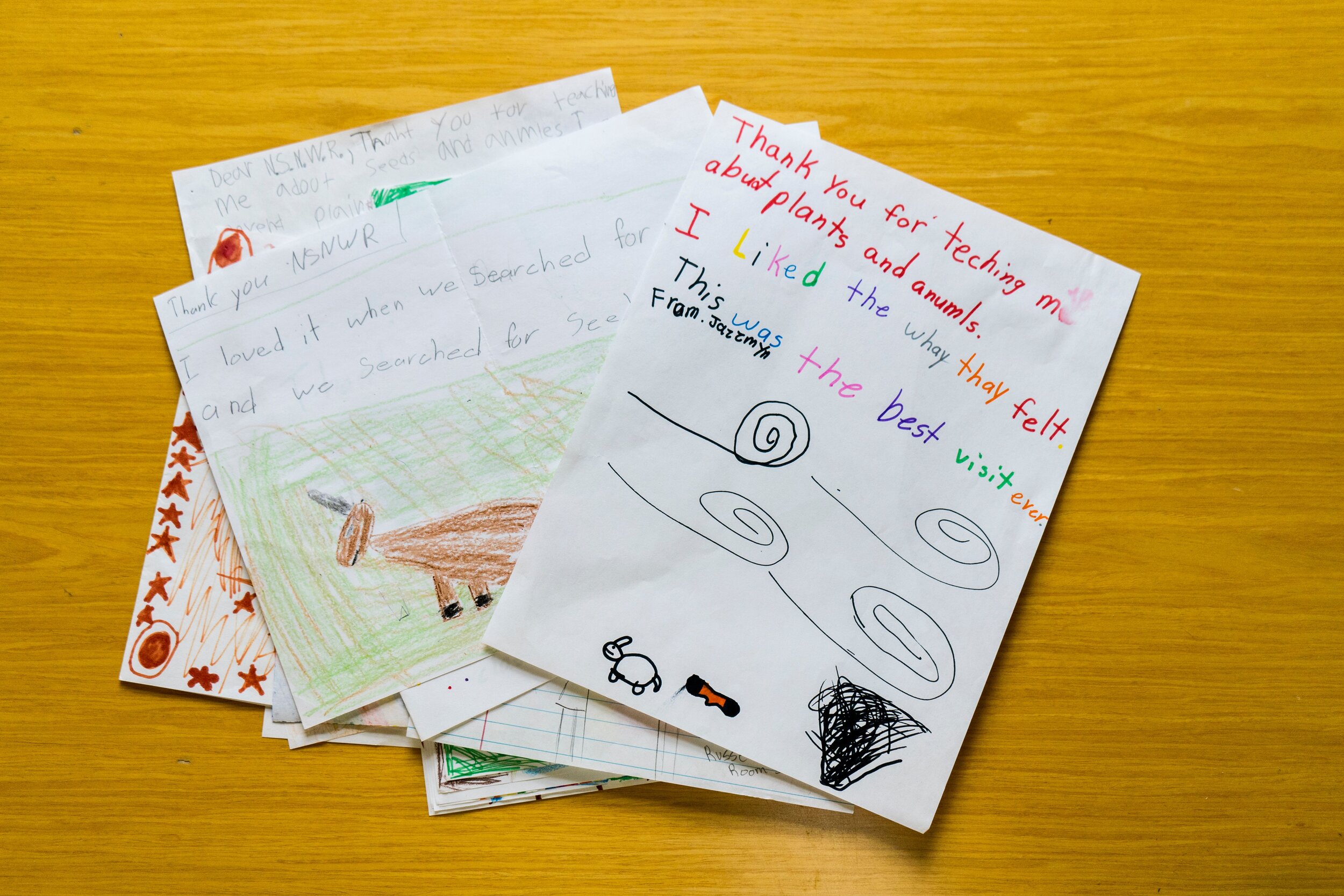

“I work with several groups of students for the entire school year. We got these awesome thank-you cards from the kids, and one of the kids, a 9-year-old, actually, wrote me a letter and drew herself, and she said: ‘Because of you, I can be a ranger too,’ ” she says. “I had it framed. It’s in my office.”

For James, he says, the campaign is also about changing the culture of conservation. For example, the National Wildlife Federation announced that it is expanding its Conservation Fellowship and intern program with positions dedicated to young biologists of color.

Beyond that, “only a few organizations went further,” wrote James, “acknowledging that they cannot achieve their mission if they do not actively work against racism and rooting out white supremacy.”