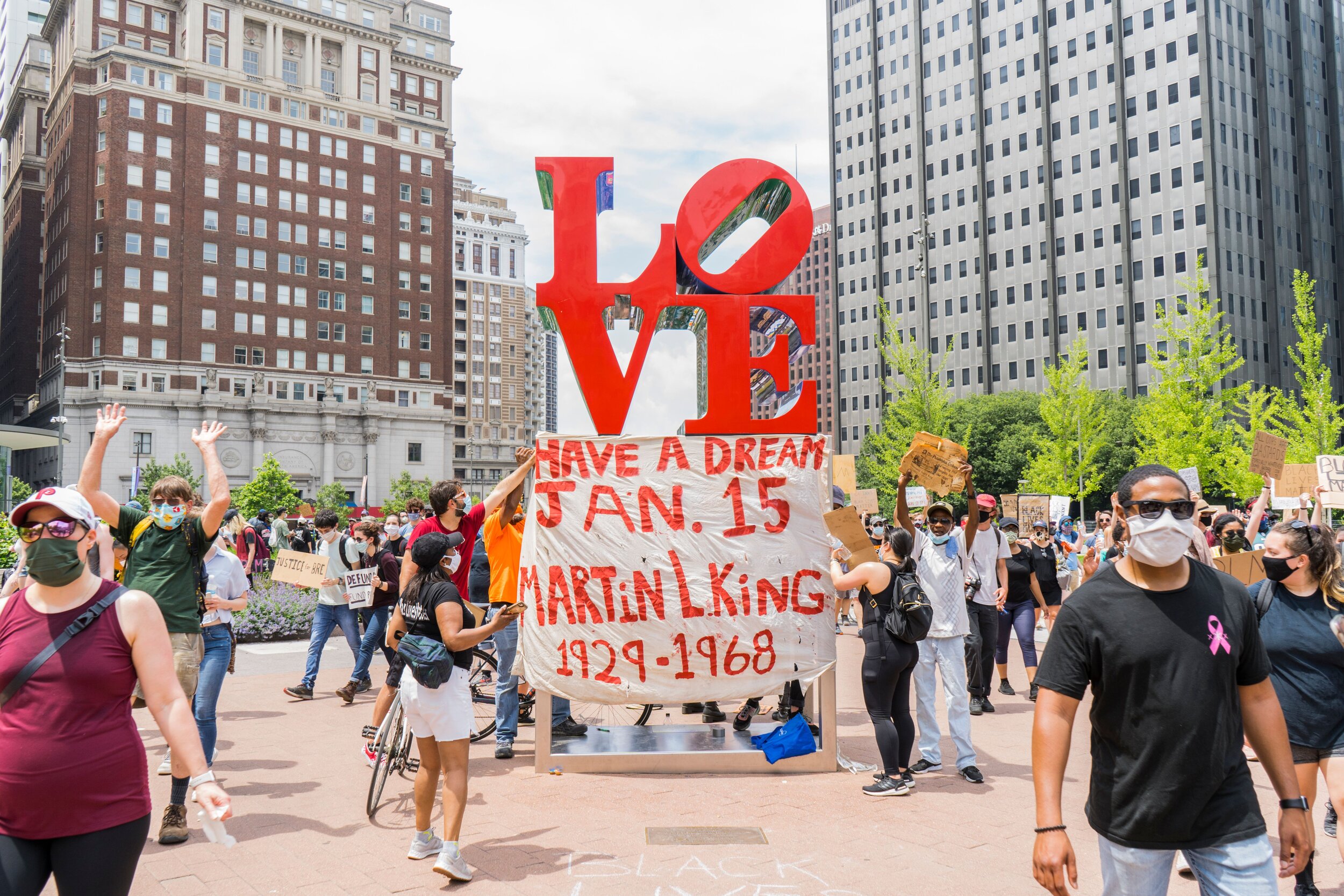

Photography by Drew Dennis

By Constance Garcia-Barrio

On Saturday, June 6, I donned eleke beads, which represent different angels in the Yoruba religion, a sister tradition to Vodun, and prayed for protection before I left home for the George Floyd protest at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. With my 73 years and two prosthetic hips, I would run hindmost if things went wrong.

I had to risk attending the march because of all the Black and Brown men in my life, including my dad, long deceased, who, when he graduated from Lincoln University in the 1930s, could only find work as an elevator operator because of his African ancestry. I marched for my enslaved but indomitable great-great-grandfather, Robert Ware, sold away from his family in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, probably in the 1840s, and never heard from again.

Above all, I marched for my son, whose mental illness adds another layer of vulnerability to his life. On one occasion, when he was off his medications, he got into a fight at Independence Mall. Once subdued and handcuffed, he taunted a police officer, who punched him in his left eye. My son kept taunting the cop, who kept punching him in the eye. Five days in the hospital under the care of an ophthalmologist resulted in little permanent damage.

We’re lucky. At age 45, my son is still alive, but the police have shot many Black men for less.

I also marched for myself at several demonstrations during the week to swell the turnout by one more body and to take the pulse of protests: in talking with people and seeing the movement firsthand, I found grounds for hope.

Coming upon a demonstration in posh Chestnut Hill shocked me.

“I’m here as an ally,” said Ethan Snyder, 22, a museum professional and one of the protesters. “As a Jew, I feel I have to stand up against fascism. Many people in this part of the city prefer peace over justice,” said Snyder, who carried a sign saying, ‘No justice, no peace.’ “They need a disruption to make them think.” Going forward, Snyder said he will continue “…to bring conversations about race into the various communities of which I am a part.”

Snyder’s comments put the ball in my court. I have to keep cleaning up my anti-Semitism—rooted in my mom’s experiences as a domestic and caterer in some Jewish households—to strengthen my bond with Jewish allies.

Juliete Salako, 23, carried a Black Lives Matter placard that Wednesday in Chestnut Hill.

“I came to Mount Airy from Nigeria with my parents when I was 12,” said Salako, a

behavior analyst with Public Health Management Corporation. “I’m demonstrating so this country can be a place where everyone is welcome. I hope to raise a family here one day.”

My sons have already experienced incidents with the police. It’s important to show support for the men in our lives, to let them see that we know I noted that a big demonstration Friday at the Upsal Street train station included children.

“We brought our 4-year-old [son] because … it was important to show him that injustice exists,” said professional cellist Timothy Knipper, 37, of Mt. Airy, “…and that addressing it is something that he can participate in … to show him why we say Black lives matter.”

Mount Airy teacher Felicia Atwell, 48, attended the march with her 17-year-old niece Kyra Adams Smith—“I’m tired of police brutality,” Kyra said—but Atwell had also hit the streets for her sons’ sake. “I’m the mother of two boys, ages 20 and 18,” said Atwell, who teaches third grade in The School District of Philadelphia. “My sons have already experienced incidents with the police. It’s important to show support for the men in our lives, to let them see that we know their lives are difficult.”

Resolve and Reeboks saw me through the huge march on Saturday. The sign on the 23 bus I caught to Center City said “11th and Market,” but the driver turned around at 12th and Girard instead. “Not my choice, folks,” he said. “The orders came down to me.”

I grew uneasy on the walk from the bus stop to 24th and the Parkway. The police blockades, armed National Guard soldiers, and detoured public transportation sealed off the area. Helicopters thumped overhead. No one could leave the locale on wheels. In case of trouble, I’d have to haul, or more realistically drag, ass.

On the other hand, the walk rewarded me. I met Natalie, 31, a Latina educator, and three of her friends were running a comfort-and-safety station. They were offering marchers free bottled water and healthy snacks.

“You need energy and fluids to march in this heat,” she said. “Two Black women came up with the idea of this comfort station. Credit where it’s due.” Natalie’s attitude was another instance where people of other races honored Black leadership. “I’m out here to protest systems that support racism, like the school-to-prison pipeline,” she added. She summed up her hours on the street by saying, “It’s the first time I’ve seen so many young white people protest. It makes me extremely happy.”

The march wasn’t the endgame, but a step, for Natalie. “I’m going to keep speaking up for a changed role for the police,” she said. “For example, they shouldn’t be in schools. You need more social services in schools to help the children.”

Family members, friends and I had burned up phone connections and the Internet during the week, messaging each other about George Floyd and making sure we were all safe in spite of the unrest. Truth to tell, I hadn’t felt ready to talk with white friends about the situation because they don’t live in fear for their men. But I took the opportunity at Saturday’s march to listen to people of other ethnicities. As Ethan Synder pointed out earlier in the week, Black and Brown people need allies. But were white people in the struggle to stay?

Near 23rd and Fairmount, I buttonholed a middle-aged white woman at random. Born in Ireland but now a U.S. citizen, she lives in Philly. “I’m at this march because racism has to stop,” she said. “As white people, we need to educate ourselves.”

“How will you work on racism after today?” I asked her.

“What should I do?” she said, flipping the script on me.

“Join the NAACP, the ACLU or the American Friends Service Committee,”

I said.

“Okay,” She looked sincere.

“Put your talents to work for a Black or Brown child,” I added. “Could you tutor a child in reading or math?” It never occurred to me to print up cards with suggestions.

We parted with an air-hug.

Patrick, 27, a white teacher in a Philly middle school attended the march because “I really want to fight for my students,” he said. “As to the future, I’ll talk with my fellow teachers, help to get them involved. I’ll advocate from the inside.”

I came upon Joshua M. Baker, 32, a lawyer of Ashkenazi Jewish and Mediterranean ancestry and an associate with Greenblatt, Pierce, Funt, and Flores LLC, a Center City firm. Baker wove through the crowd, giving out his card and offering pro bono legal services to anyone arrested for protesting.

“I haven’t heard of arrests today,” he said, “but I’ll be taking on civil rights cases against police officers who assaulted protesters [at other marches].” Baker’s professional life will keep him on the frontlines of the struggle against racism.

“My practice is 90 percent plaintiffs’ civil rights and employment discrimination,” he told me. “The civil rights cases are practically all on behalf of young Black and Brown people … arrested [or] assaulted by the police for no good reason.”

Geri, 57, a white woman, had also come to assist with difficulties that might arise.

“I’m here as a witness,” she said. “I’m with Up Against the Law,” she said, speaking of a Philadelphia-based collective of volunteers who support activists by helping them know their rights. “It’s useful to have observers on hand when there’s an incident,” she said. “And I’ve learned to shut up and listen [to Black people], and I’ll go on doing that.”

Marchers urged each other to speak up about racial justice—some white protesters with signs saying “white silence is violence”—but represented a range of ideas about how to achieve it. Len, 35, handed out flyers that said, “white people, take a stand for reparations for the African community.”

“We have to do more than unlearn racism,” said Len, attending under the auspices of the African People’s Socialist Party. “White people profited from slavery. Black people are due reparations. I’ll keep on working towards that.”

In the end, my fear of a riot came to nothing, but I did become angry over one incident. A white 50-ish couple stalked along the Parkway, the man looking irate and perplexed at the demonstration. In walking, he banged into me on purpose. I wasn’t frightened—this crowd would have rushed to the aid of a gray-haired Black woman—but I got mad. I wanted to slam him with an epithet that involved the word mother, but I stopped short of doing so. Maybe the man wanted to ignite an incident, and I wanted no part of that. Besides, he served as a reminder of the opposition that lay ahead.

I had reason to rejoice as I trekked back to the 23. After the weeklong protests, especially Saturday’s march, I know that the nation can seize this chance to undo racism, thanks to unique circumstances. The protests and willingness may reflect a silver lining of COVID-19, the woman from Ireland suggested. The virus has brought upheaval to our lives, softened us with illness and deaths and maybe left us more open to change.

Technology also mid-wifed this moment. Countless Black people have been killed here since 1619, when slavery in British North America began, but today smartphones captured the words and images of George Floyd begging for his life. Technology leaves no room for denial.

Our country has a fighting chance for change, judging by the marchers of all ages and colors, but especially the many white young adults.

Their outrage promises partnership for Black and Brown people in dismantling racist systems: poorer education, deficient health care, a skewed legal system, tainted air and water, nutrition deserts and all the other systems that shackle people of color. These young people seem ready to take on perhaps painful introspection.

“We have to ask ourselves how we feel about ourselves when we can’t fall back on whiteness to give ourselves value,” one young white man said. I also took heart because the people I talked with didn’t see Saturday as a one-and-done event. Most of them had concrete plans for keeping the momentum of the march in their lives.

Atwell, a Black woman from Mount Airy, made another key point.

“I’m so proud of how other cities, not just Philadelphia, are holding marches,” she said. “It shows the strength of the movement.”

Moreover, George Floyd protests have jumped the Atlantic. Protesters in England toppled the statue of famed slave trader Edward Colston (1636–1721), and threw it into Bristol Harbor. The city of Antwerp, Belgium, removed the statue of King Leopold II (1835–1909), said to have ordered the slaughter of upwards of 10 million people in the Congo, after anti-racist protesters defaced it.

In Philadelphia, during the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the Founding Fathers botched matters of race by allowing slavery and deciding that an enslaved Black person should count as three-fifths of a man for purposes of representation in Congress.

Now, more than 230 years later, George Floyd and the marchers have given the nation a second chance for racial justice.