The Trump administration has openly questioned climate science, but there are more reasons to be concerned about the president’s budget proposal

by Jared Brey

Three years ago, after decades of waiting and pestering city officials to do something, residents of Bridesburg, a riverside community in Philadelphia between Frankford and the great Northeast, met at a catering hall to start planning for the future of three big gashes of possibly polluted, formerly industrial land in their neighborhood. In Eastwick, on the other end of town, officials are finally starting to reckon with decades of neglect. They’re beginning the work of cleaning up the area around two former landfills aside Darby Creek, which have been listed since the early 2000s as contaminated Superfund sites, designated for priority cleanup due to the risks they pose to human health. A few miles north of there, on the banks of the Schuylkill, the University of Pennsylvania recently cut ribbon on the Pennovation Center, where it hopes to incubate the next generation of health and tech pioneers. And all around the city, the Philadelphia Water Department is working to build out neighborhoods with green stormwater infrastructure to keep pollutants from flowing into our waterways.

What do these efforts have in common?

None of them would be happening without some kind of support from the Environmental Protection Agency.

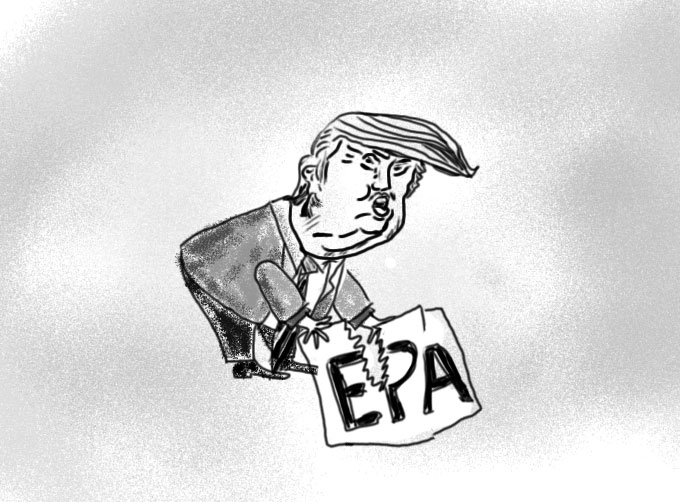

Since Donald Trump was elected president, advocates have been reading the tea leaves, trying to predict how sharply Trump plans to depart from the modest environmental progress made under the Obama administration. The indications so far have been grim. In February, the Senate confirmed Scott Pruitt, a former Oklahoma attorney general who’d made a career of battling federal environmental regulations, as the new EPA administrator. Then in March, the Trump administration released a preliminary budget proposal calling for 3,200 layoffs and a 31 percent reduction to the agency’s funding.

But the budget isn’t set in stone, and many advocates quietly doubt Congress will approve such deep cuts to the agency. The real negotiations won’t start until later in the year. In the meantime, residents and state and local governments are left to wonder how much leaner the EPA can get before we start paying for it in the quality of our air and waterways.

“Are we going to feel it immediately? I’m not sure,” said Maurice Sampson, the Eastern Pennsylvania director for Clean Water Action, a group that formed around the push to adopt the Clean Water Act in 1972. “What we’ve built over the last 40 years to protect the environment, which we know has had a positive impact—what happens when you start untangling that?”

Shifting responsibility to states and cities

Donald Trump, who tends to reveal his governing philosophies via Twitter, once famously claimed that climate change was a hoax invented by the Chinese to make American industry less competitive. That such a belief could be held by the president of the United States is cause for alarm among climate scientists, who agree in virtual unanimity that global warming is real, and a threat to life on earth. But advocates say that even people who reject the science of climate change may find something to worry about in Trump’s developing environmental policy.

Of all the government agencies whose budgets are slated to shrink to make room for a $54 billion increase in military spending, the Environmental Protection Agency would be hit the hardest. In addition to the funding and staffing cuts, Trump has targeted a broad range of programs and grants to be reduced or eliminated in the budget. If the cuts go through as is, according to a detailed but “confidential and pre-decisional” budget memo published by The Washington Post, there will be less money for Superfund site cleanups, for brownfields planning, for oil-spill prevention and even for childhood lead safety programs.

Pruitt has said his approach to the administration of the EPA is guided by a belief that states should take on more of the responsibility for protecting the environment, and the EPA shouldn’t get involved in anything beyond its core mission. But the state Department of Environmental Protection relies on federal funding to implement many environmental protection programs, as Acting Secretary Patrick McDonnell said in a letter to Pruitt in March. The proposed cuts would have an “immediate and devastating effect” on the state’s ability to protect the safety of its air and water by reducing funding for local water system inspections. In addition, by paring down brownfields planning, the budget would stifle job creation and economic growth, McDonnell wrote.

J.J. Abbott, press secretary for Gov. Tom Wolf, noted that the federal cuts would harm the DEP’s ability to do its job without touching its responsibility for the environment, putting it in an impossible spot.

Later in March, Philadelphia’s Office of Sustainability published an action guide, outlining the potential consequences of Trump’s budget proposal for the city’s environmental health, encouraging Philadelphians to mobilize in opposition to the cuts. In a press release, Mayor Jim Kenney said the Trump administration’s proposal is “irresponsible” in light of climate change threats. “Additionally,” he said, “the proposed Trump budget would have immediate and drastic effects on many programs that Philadelphians rely on, such as those that support local air pollution prevention efforts, or that help residents save money on energy.”

The EPA, for its part, has been quiet. Regional representatives did not respond to three requests for an interview.

Advocates do have some reasons to hope. Others have pointed out that back in the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan was elected president, he also began his term by making industry-friendly appointments and proposing substantial budget cuts. But the Reagan administration wasn’t able to completely dismantle the agency; congressional investigations enforced some senior appointees to resign, and, while environmentalists still see the 1980s as a damaging time for environmental policy, their worst fears were never realized.

“The whole budget is clearly a farce,” said Joseph Minott, executive director of the Clean Air Council. “It is unimaginable that one of the largest public-health protection organizations would be gutted by any administration. It just does not make any sense. Clearly, this is sort of a political document and not a serious budget, and I hope and pray that Congress will see it as such.”

In Philadelphia, at least in the short term, cuts to the EPA are unlikely to affect the quality of the drinking water. Joanne Dahme, general manager of public affairs for the Philadelphia Water Department, said that all of the department’s work is funded locally, by ratepayers. And that even includes the massive, forward-looking Green City, Clean Waters program. Sources said, too, that EPA funds that have already been granted for local brownfields planning and Superfund cleanups are not likely in jeopardy. And Christine Knapp, director of the city’s Office of Sustainability, said in a November 2016 interview with Grid that Greenworks, the local sustainability plan, won’t be affected by the federal budget or policies.

Trump’s approach to environmental regulation does, of course, have some supporters. Rachel Gleason, executive director of Pennsylvania Coal Alliance, said her group applauds the Trump administration’s decision to reconsider Barack Obama’s climate and environment policie

s. And Kevin Sunday, who works on energy and environment issues for the Pennsylvania Chamber of Commerce, said that every government program could use some “thoughtful cutting.” The Chamber of Commerce only hopes that budget cuts don’t affect permit-review timelines.

Not all business leaders are in favor of the proposed cuts. In a recent op-ed in The New York Times, Michael Bloomberg argued that businesses will continue to pursue the aims of the Clean Power Plan even if the regulations are undone. And Jon Jensen, a technical consultant at MaGrann Associates and co-chair of the Delaware Valley Green Building Council, said local builders are demonstrating a voluntary commitment to more sustainable construction practices because it benefits their bottom line as well as the environment.

But major reductions in funding could mean fewer state inspections of local water systems. And bold programs such as Green City, Clean Waters may never have gotten started without buy-in from the EPA. There’s also the question of progress. After all, it’s not as though the environment is perfectly safe and healthy right now. Environmental quality needs constant improvement, and most advocates say the EPA has never been as robust as it should be.

A ‘massive void’ for communities of color

Perhaps most concerning of all for cities like Philadelphia, where a majority of citizens are people of color and a quarter of the population is poor, is the Trump administration’s push to eliminate the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice, which was created in the early 1990s and is charged with ensuring that all communities receive equal protection from environmental harms. Historically, that hasn’t been the case. Studies have found that poor people and communities of color are likelier to live in areas with lower air and water quality and in closer proximity to toxic waste sites. Last year, a report by PennEnvironment and ACTION United revealed that areas within the potential blast zone of oil trains running through the city are populated mostly by people of color, while areas outside the blast zones are two-thirds white.

Jacqueline Patterson, director of the NAACP’s Environmental and Climate Justice Program, said the Office of Environmental Justice has been a crucial watchdog for marginalized communities.

“The office has done a lot…” Patterson said. “I think a lot of people, especially communities that aren’t necessarily seeing relief, would be concerned about what hasn’t been done. But with the constraints that they have, of being a relatively small office with a relatively small budget and varying degrees of political embrace of what they’re doing, I think they’ve done a lot.”

The Office of Environmental Justice has been able to move resources into communities that are “suffering under environmental-justice challenges,” she said, as well as provide technical assistance to those communities and improve their level of civic engagement. Moreover, the office provides an environmental-justice lens that informs the work of the entire EPA, as well as other federal agencies, she said.

It’s also the case that communities of color and poor communities, often one and the same, are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, according to the NAACP. Coupled with the other budget cuts proposed for the EPA, Patterson said, the elimination of the Office of Environmental Justice could leave a “massive void” for marginalized communities.

“Seventy-one percent of African-Americans live in violation of our existing air quality standards, and so if we have fewer standards and less monitoring and enforcement, how is that number going to be affected? Is it going to be 100 percent now?” Patterson said.

Diane Sicotte, an environmental sociologist at Drexel University and author of “From Workshop to Waste Magnet: Environmental Inequality in the Philadelphia Region,” said areas around Philadelphia such as Camden and Chester could be particularly threatened by further degradation of air quality standards.

“When you have poor populations, there are so many things that can impact and degrade their health,” Sicotte said. “And the health problems that people get from pollution are so common—heart disease, lung disease, asthma, lung cancer, all of that stuff—they’re so common, how can you tease out that this is from the incinerator, and that’s from stress, and that’s from automotive pollution? But there’s a cumulative burden on people’s health, particularly people who are poor.”

What would be the result of a diminished EPA?

“More people will die of lung cancer, more people will die of heart disease, because air pollution kills people,” she said. “It’s really that simple. Whether you die of an asthma attack or heart disease, it kills you. Water pollution kills people. It gives people cancer. It gives people kidney disease. It does all kinds of things that happen slowly and almost, sometimes, invisibly… But, people just will die. It’s really that simple. And that’s not even thinking about what it does to the ecosystem.”

From an imperfect ally to a clear adversary

The relationship between the EPA and environmental advocacy groups is a complicated one. On the one hand, environmentalists say, the EPA has always been underfunded, and only adopts regulations that industry can tolerate. On the other, since its creation in 1970, the EPA has been the only official lever of power at the movement’s disposal.

Under the Obama administration, the environmental movement, which encompasses a vast array of focused causes, had an imperfect ally. In 2015, the administration announced the Clean Power Plan, its signature effort to combat climate change by setting a range of targets for reduced greenhouse-gas emissions in states across the country. Later that year, the U.S. signed on to the Paris Agreement, aimed at reducing carbon emissions worldwide.

Advocates say both plans were important foundations for future action on climate change, even if they fall short of setting standards that scientists say are necessary to keep the globe from warming too much. Both plans also face uncertain futures under the Trump administration.

Sam Bernhardt, the senior Pennsylvania organizer for Food & Water Watch, said his group has been saying for years that the EPA hasn’t been doing its job, and is now in the somewhat awkward position of rallying to save it. But in some ways, he said, it’s easier to deal with a clear adversary than an imperfect ally.

“Obama was not going to get us to the place where we need to be on climate change,” Bernhardt said. “Hillary Clinton wasn’t going to, either. And so in some sense, this is an opportunity for us to set the right course. Instead of fighting against the Clean Power Plan, which is an awful thing to have to fight against—they named it very well, they didn’t name it the Let’s Build Fracked-Gas Power Plants Plan—we now have Trump and Scott Pruitt. And we need to seize on that.”