Photo courtesy of Michelle Johnson

A Pennsylvania woman fights against the natural gas pipelines that threaten the region’s water supply

by Justin Klugh

Malinda Harnish Clatterbuck goes for a run almost every morning. Early in the day, the sun crawls across the Tucquan Glen, a nature preserve in southern Lancaster County, bringing to life its seven ravines teeming with greenery.

The concealment of the trickling glade is exactly the habitat to which her instincts lead her. “People who have heard me speak are shocked to find out that I am introverted and that I prefer to live in a hole in the woods by myself,” Clatterbuck says.

The woods hold a deep history, not just of the undisturbed River Hills, but of Clatterbuck herself. She has lived all over the country but returned to her Lancaster birthplace in the wake of her father’s death and moved back into her childhood home—one of 10 houses on a 2-mile stretch of road—where she has raised a pair of daughters with her husband, Mark.

“I’ve come to appreciate and value how your geography shapes who you are and how you see the world,” Clatterbuck says. “People are different in different parts of our country because of geography, I think. Coming back home after my father died helped me find my roots… and what I appreciate about this geography: the rocks and the streams, the mountain laurel on our road. You come to know each plant and tree intimately.”

Tucked away under oaks, beeches and a dense hemlock canopy, it’s easy to see how a resident could come to treasure and embody the private Tucquan geography as Clatterbuck has. But now, a sharp turn in her life has required her to abandon the tranquility of life in the Tucquan Glen, and enter a fight to protect it.

Clatterbuck, a pastor, counselor and educator, has some harsh (and unprintable) words for what she thinks of her adversaries. To paraphrase: “People can be [jerks]. Trees can’t be.”

It starts with a knock on the door. A man with a clipboard tells a homeowner their house is in the way of the installation of a massive construction project—in this case, the 198-mile, $3 billion Atlantic Sunrise natural gas pipeline that will transport 1.7 billion cubic feet of gas per day—and that knock becomes a homing beacon for similarly affected community members, protesters, police, politicians, reporters and, of course, the aforementioned jerks.

Facing a system of intimidation and bullying—Clatterbuck tells stories of Amish neighbors who were lied to about the regulations of their compensation in regard to eminent domain laws—residents affected by the pipeline have been unified by a movement, Lancaster Against Pipelines, started by Clatterbuck and her husband.

“We used to think we were busy and life was full,” Clatterbuck reflects wistfully. “And then we started this work.”

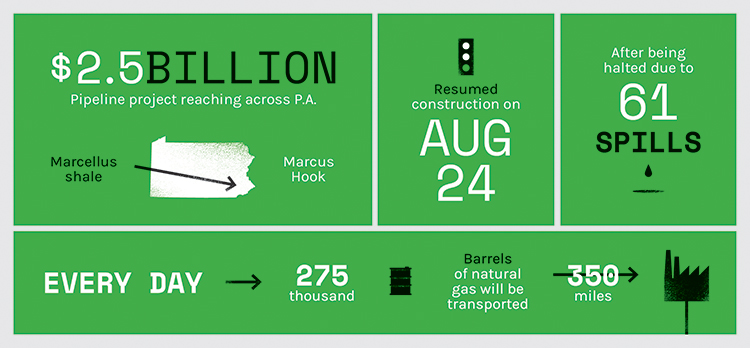

Pennsylvania is sitting on a mother lode of natural gas, and energy companies are desperate to build the pipelines to procure and export it. With 6,800 miles of pipeline in place, 4,600 more miles planned and the continued approval of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, they seem poised to get it. The pipeline, a product of Oklahoma-based energy business Williams Cos., is being mapped to reach the natural gas in the Marcellus shale of Northeastern Pennsylvania, with Williams Cos. intending to transport the resource overseas. The pipeline is planned to be installed through 36.5 miles of Lancaster County including the rural Conestoga and Manor townships in which the Tucquan Glen is housed, touching 10 Pennsylvania counties and 200 miles of state terrain in total.

Williams Cos., which touts the 8,000 jobs and $1.6 billion economic impact of a potential pipeline, has a history of safety failures since 2003, including three accidents in rapid succession from March to April 2014. In one case in Sauvie Island, Oregon, The Oregonian reported that the company was aware of gas leaks at transfer stations, but did not notify the public for two months. The leaks eventually resulted in an evacuation and the closure of a school.

“What is left sacred?” Clatterbuck asks. “At what point is the destruction itself bad enough that you say, ‘No, this can’t happen’? This is just for greed. This is for export. This isn’t good for the community.”

Some might call it a victory that several months after the knock on their door, the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline was no longer planned to go through the Clatterbucks’ home. However, in the fight for a community, there are no winners until no one loses, as the pipeline is still proposed to invade some neighbors’ properties several miles away.

“We are doing this work for our community,” Clatterbuck says. “We live in a community. I know in our country we try to pretend that we don’t. I care about the people who have it going through their backyard and they have a right to say ‘no.’ Even if the pipeline comes through on their property, I’m not going to move out of my community. I will [live and protest] on their property as long as they let me and continue to get arrested.”

The reach of the environmental damage the pipeline could cause goes beyond the Clatterbucks’ neighborhood. The 6-mile Tucquan Creek flows west from Rawlinsville, Pennsylvania, to its confluence with Clark Run before joining the Susquehanna River. The creek’s twisted journey contributed to its name, which translates to “winding water,” and has been referred to as “Seven Crossings,” given the amount of times hikers would have to step through the creek to continue on their way. But Tucquan is an oasis. Less than 15 percent of Lancaster’s land sprouts natural forests, and most of it is not dense enough for the official Pennsylvania Wild and Scenic River designations that Tucquan has received. Tucquan Glen would suffer some of the most sprawling effects as forests of its kind conserve and sustain a local water supply, which in this area is used to cultivate the region’s farmlands.

As the creek joins the Susquehanna River and flows toward the Chesapeake Bay, the fallout of a pipeline’s installation could taint not only these water supplies, but those of communities downstream. Pipelines do not permit the replanting of trees after the devastation of their installment, meaning that any trees uprooted in the process would be gone for good.

“It’s this game that’s played for the industry’s benefit, sacrificing everybody else on the earth in the process,” Clatterbuck says, exasperated. In darker moments, she turns to Jane Austen novels to restore her faith in happy endings. “Story is really important to me.”

This story has an ending difficult to tell over the growl of idling construction vehicles. But the Clatterbucks, Lancaster Against Pipelines and other supporters will keep pushing back, a steady current against destruction, protecting the “winding water” and the life it brings to the neighboring region.

An encampment called The Stand has become a local comparison to the ongoing standoff in Standing Rock, North Dakota, where Clatterbuck’s husband and daughter traveled earlier in the year and witnessed a violent clash.

The lesson is taught across the nation as environmental legislation is scribbled out: Tampering with the land can lead to all sorts of trouble, and when you change the geography, you change the people living on it.

“I’m learning to get my [back up],” says Clatterbuck, the reformed forest hermit, although she (again) uses more colorful language. “I’m going to make enemies standing up for what’s right, and I’ve decided that it’s worth it.”