illustration by Kathleen White

Making Tracks

by Jon Hurdle

This year’s deadly Amtrak derailment in Northeast Philadelphia was a tragic reminder of the consequences of failing to invest in infrastructure in a way that ensures the safety of the public.

On that stretch of track, the absence of Positive Train Control, a technology that automatically slows speeding trains, might have prevented the crash that killed eight people, injured more than 200, and halted trains between Philadelphia and New York for days. In the ensuing weeks, Philadelphians saw the wreckage and the faces of the affected passengers all over the national news as officials sought answers and politicians renewed the debate over whose job it is to make sure needed upgrades happen quickly enough—as well as who will pay for them.

The mangled Amtrak cars in Philadelphia dented public confidence nationally, albeit temporarily. They also refocused attention on the ongoing need to provide infrastructure of all kinds that ensures public safety and advances sustainability goals such as conserving energy, cutting greenhouse gas emissions and encouraging transit use.

Philadelphia’s public agencies and some private companies are working to ensure the continued safe operation of all the things that we take for granted in our daily lives: rail and bus lines, water mains, gas pipes, bridges and transit services. Without them, our lives would grind to a halt, as residents of New Orleans or New York will tell you: We are one more Katrina or Superstorm Sandy away from a direct hit that will test our mettle as a city. We need to upgrade this infrastructure to meet both safety and new environmental goals in a city where many such facilities date back to the 19th century.

The process of renewal and enhancement is taking place in the national context of a massive shortfall in infrastructure spending, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.

data-animation-override>

“In its 2013 report card on U.S. infrastructure needs, the ASCE gave the country an overall grade of D+, or “poor,” saying roads, schools, transit and levees were among the facilities in the worst condition, while railroads and bridges earned only a C+. Getting it all up to the engineering society’s desired standard would require spending a breathtaking $3.6 trillion, or about three and a half times the federal stimulus during the 2008–’09 recession, by 2020, the report said.”

Pennsylvania got a similarly poor assessment, with seven D grades for different kinds of infrastructure, and the highest percentage of structurally deficient bridges—almost one in four—of any state in the country. Dozens of those bridges are in Philadelphia. It’s important to note that being deemed structurally deficient does not mean that a bridge is unsafe to cross, but some of them are already showing signs of advanced deterioration of primary structural elements, which makes it imperative to fix them.

The age of Philadelphia’s infrastructure means that 75 percent or more of its agencies’ budgets will be dedicated to maintenance, says Barry Seymour, executive director of the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, which focuses on transportation planning.

“Because we have bridges that are 100 years old and power stations that are 100 years old, the majority of funding is always going to go to maintenance,” he says. “But at the same time, we are starting to look at expansion opportunities” driven largely by the 2013 increase in Pennsylvania’s transportation funding.

Although older systems demand most of the available infrastructure dollars, they can also make it easier for planners to pursue sustainable goals such as biking, walking and public transit because those cities were designed before the age of the automobile.

Easing our minds, and our commutes

If you’ve ever sat in traffic on Route 76 or Roosevelt Boulevard, you’ve experienced firsthand what happens when we don’t invest in public infrastructure. Those who have tried to travel over the Ben Franklin Bridge during repairs have also experienced the flip side: disruption from necessary repair work.

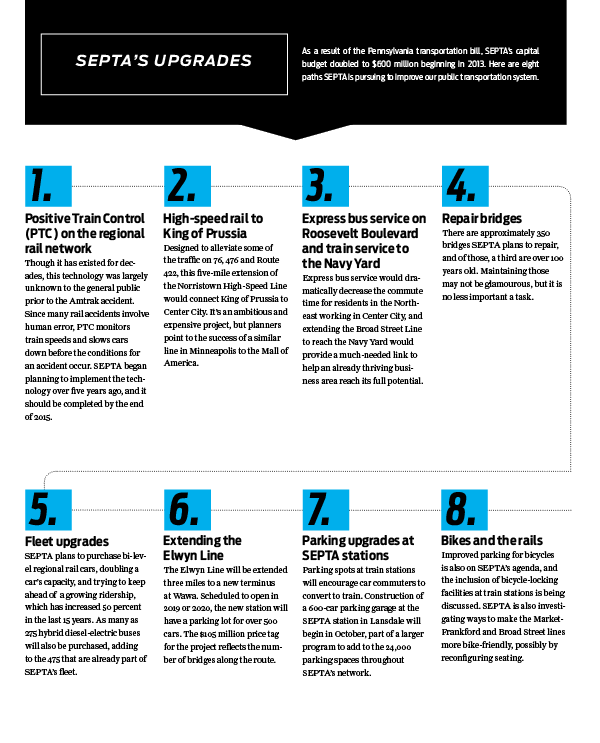

While not all of our transportation problems will be solved any time soon, improvements are on the way. Pennsylvania’s infusion of transportation funds has given SEPTA much needed support. Its capital budget doubled to $600 million starting in 2013 as a result of that year’s statewide transportation bill.

The system-wide improvements and investments range from replacing ’20s and ’30s-era electrical substations to a possible new regional rail route connecting Center City to King of Prussia. Also slated for repair are about 350 bridges—around a third of which are more than 100 years old. Some improvements, like Positive Train Control (PTC) on our rail lines, will also put us ahead of most American cities when it comes to public safety.

The PTC installation on the regional rail network, a project that began some five years before the Amtrak accident, is on schedule for completion by the end of 2015, says Richard Burnfield, SEPTA’s chief financial officer.

Although the PTC installation began before the latest infusion of funds, Burnfield called the project the agency’s “most urgent” capital project because of its importance in ensuring public safety. He said only SEPTA, Amtrak and the Metrolink system in California will have the technology fully installed by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, the agency is working on three possible projects that would, if realized, mark major developments in its infrastructure and lead to further gains in transit ridership.

data-animation-override>

“The top of SEPTA’s priority list, and the most ambitious, is the proposed five-mile extension of the Norristown High Speed Line to King of Prussia, a project that would boost transit ridership to and from the suburban shopping mall and office park while reducing traffic on notoriously congested local highways including the Schuylkill Expressway, the Pennsylvania Turnpike and Route 422. ”

In considering the new line, officials are encouraged by the example of a rail service that was built into the Mall of America near Minneapolis. That service has been “extremely successful” in attracting riders and shoppers, says Byron Comati, the agency’s director of strategic planning and analysis.

Elsewhere, SEPTA is considering adding express bus service along the notoriously dangerous Roosevelt Boulevard in northeast Philadelphia as part of the redevelopment of that highway, and it continues to evaluate the possibility of extending the Broad Street subway into the Navy Yard to serve that community’s growing work force and its anticipated residential population as the development continues in coming years.

Also underway is the restoration of three miles of regional rail track beyond Elwyn, a stretch that was closed in the early 1980s because it fell into disrepair, but is due to reopen in 2019 or 2020 with a new station and a park-and-ride for over 500 cars. A $105 million price tag for the project largely reflects the high number of bridges along the route, Burnfield said.

Meanwhile, SEPTA’s fleet is being upgraded. To its roster of 1,400 buses, it will add as many as 275 new hybrid diesel-electric buses to the approximately 475 already in operation. The hybrid buses show a steady reduction in air emissions with successive models, are easier to maintain than conventional diesels, and have a longer useful life of up to 13 or 14 years, said Comati. Thirteen electric locomotives are also on their way, and SEPTA will soon invite bids to supply bi-level rail cars in anticipation of further increases in ridership, which has grown 50 percent in the last 15 years, Burnfield says.

“You can’t make the trains any longer, so we’re going with bi-levels,” he adds.

To encourage people to take the train, SEPTA will add 24,000 parking spaces to rail line lots, as well as bike parking amenities. Asked whether the addition of parking lots runs counter to SEPTA’s stated sustainability goals, Burnfield says the lots are intended to deter people from driving their cars into the city, and construction standards will include the use of energy-efficient lighting and better management of stormwater runoff.

“There is a lot of transit-oriented development springing up around our stations,” he says, referring to development that is targeted in areas that have access to public transportation. “You have to balance the overall needs of the region by providing parking so that folks are driving to a train station rather than driving 20, 30, 40 miles down the Schuylkill Expressway or Interstate 95.”

All the capital projects, whether actual or potential, are being underpinned by principles such as energy efficiency, transit-oriented development and stormwater management, Comati says. He argues that sustainability has become an integral part of the transportation planning process in less than a decade.

“Six or seven years ago, in the transportation industry, you didn’t find it,” he says. “Now it’s core thinking.”

The tangle of underground pipes crucial to our daily lives

A lot of the infrastructure that we rely on is hidden, although we depend on it every day. We take for granted that we are able to turn on the tap and get unlimited clean water or fire up the indoor gas stove to set the tea kettle singing in the morning. When it works, we don’t think about it. When it doesn’t, our lives can be thrown into chaos with a flooded roadway or a dangerous gas leak in the kitchen.

On at least one front, Philadelphia is leading the way nationally: our plan to control the water from heavy rains that can cause havoc both in our basements and at our sewage treatment centers. When the system becomes overwhelmed by a heavy rainstorm, raw sewage flows into the Delaware River over 50 times a year in what are called “combined sewer overflows.”

Anthony Kane, vice president for research and development at the nonprofit Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure (ISI), says older infrastructure such as wastewater systems that combine sewer and stormwater flows are prompting cities to look for sustainable solutions. One big constraint? Whether it is water or gas lines, it’s extremely expensive to replace all those pipes.

“These limitations are forcing cities to be more creative and to look beyond the traditional ‘gray infrastructure’ solutions often to more sustainable options,” he says.

Philadelphia’s long-term green infrastructure plan is called Green City, Clean Waters. It calls for solutions like planted road medians and green roofs to manage stormwater, rather than solutions such as underground retention tanks, an example of the gray infrastructure Kane mentions. These strategies are keeping our rivers and creeks clean, as well as transforming the way that Philadelphia looks. In order to help fund the improvements, the water department had to change its rate structure, especially for commercial properties. Properties that allow water to infiltrate into the ground now pay less; uses like parking lots or other impermeable surfaces pay more. Overall, its 25-year, $2.4 billion plan, is a fraction of the cost of building new pipes underneath the city.

Paying the piper, now or later

data-animation-override>

“The critical issue of funding was at the heart of last year’s heated standoff between City Council and the Nutter Administration about the potential sale of Philadelphia Gas Works (PGW), the nation’s largest municipally owned gas utility. It has a network of cast-iron pipes so vast that the current replacement program is scheduled to take 88 years. ”

In a highly politicized vote that was in part a reaction to the Council’s claim not to have been consulted on the deal, it summarily rejected a $1.86 billion offer to buy the utility in December last year. UIL, the Connecticut-based energy-distribution company that had been selected to buy PGW, had said it would be able to replace the pipelines much faster than under public ownership because it had access to the capital markets.

If the private sector won’t be paying for the upgrades, that means the public will. A new plan submitted by PGW to the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission on Sept. 1 would accelerate the 88-year schedule to 48 years. The utility proposed paying for the upgrade by charging customers an additional fee that’s designated to pay for infrastructure improvements—the Distribution System Improvement Charge. The new fee, if approved, would cost a typical residential customer an extra $1.65 per month.

Why should we care about replacement schedules?

Barry O’Sullivan, a spokesman for PGW, says pipeline replacement, at whatever rate, would reduce leakage of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, but adds that PGW does not record leakage rates from particular locations.

He also says the pipeline-replacement program does not indicate there is any danger to the public from deteriorating pipes, or that there has been a shortfall in past investment.

“It’s not the case that the existing infrastructure is past its useful life,” he says. “That is the rate at which we can replace the pipe. It’s not because we are playing catch-up.”

But PGW’s critics don’t see it that way.

Jonathan Peress, the air policy director for natural gas at the Environmental Defense Fund, says there is no “imminent safety threat” from PGW’s aging pipe network, but argues that the system is leaking an “unacceptably high level of methane into the at mosphere,” which is exacerbating climate change.

“There are no doubt many, many leaks in the underground system, and there are valid reasons for them to move forward,” he says, referring to PGW’s pipeline replacement program.

The Clean Air Council, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit, agrees that the pipes need to be replaced, and argues that past explosions show that the pipeline network does represent a danger to the public, and noting a study by the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission that estimated that two-thirds of the system was “at risk.”

Climate change is testing the resiliency of our infrastructure

Our critical infrastructure is in a long boxing match with time and weather. Every year, as the temperature repeatedly goes up and down, causing “freeze thaw events,” our bridges, pipes and roadways are getting jabbed over and over again. Our concrete crumbles, the pipes rot and clog, and structural deficiencies start to become dangerous. When a big storm like Hurricane Sandy comes, it can be the knockout punch that takes something down.

Philadelphia climate models tell us that the city is going to be hotter and wetter, and that the hotter temperatures are not going to be in the winter. Katherine Gajewski, Director of the City of Philadelphia’s Office of Sustainability, says that sustainability is being promoted among city agencies around the issue of climate change. Officials overseeing areas such as water, gas and streets—all of which are vulnerable to higher temperatures, bigger storms or rising seas—have been taking a coordinated approach to planning for climate change.

data-animation-override>

““We’ve started to see the effects of a changing climate with more variable freeze-thaw events,” Gajewski says, “and we’re starting to see more negative impacts on those infrastructure assets.” ”

Gajewski adds that her office got an unexpectedly positive response from the affected departments in response to its call for a joint approach to climate change.

“Across the board, they recognized it as something that they really needed to be focused on, and as a result took very seriously.”

Funding, as always, will be a constraining factor, and Gajewski is not convinced that government can’t do things as efficiently as the private sector. Citing the example of the results of energy use in commercial buildings that are now complying with new law to disclose use, Gajewski says, “It’s a more nuanced answer than just saying the private sector is doing better than government because it’s not really the full story.”

Sarah Wu, Deputy Director for Planning in the Office of Sustainability, says city departments are already beginning to adapt to the warmer and wetter conditions that are projected to affect the Philadelphia in coming decades.

The Streets Department, for instance, is starting to move electrical systems for traffic signals from underground locations where they are vulnerable to flooding to elevated positions where they won’t be affected by the increasing number of heavy downpours that are expected to come with climate change.

And the Department of Parks and Recreation is thinking about shifting HVAC systems onto the roofs of recreation centers to remove the risk that the systems could be flooded, Wu says.

She adds that despite the higher expected temperatures, Philadelphia will still have to deal with the freeze-thaw cycles that traditionally create problems for infrastructure, such as road surfaces.

Although City officials have been receptive to the calls by Wu’s office for a systematic approach to such resiliency planning, some have already been making localized changes to their systems in response to changing climatic conditions.

“They are saying, ‘This is not news to us; we know the weather has been getting wetter,’” Wu says. “We’re not starting with zero knowledge of what warmer and wetter weather looks like.”

Asked whether Philadelphia’s infrastructure is ready for climate change, Wu says the city will be better positioned to withstand rising sea levels than other big East Coast cities such as Boston and New York because it is 90 miles from the mouth of the Delaware River, and so is not directly exposed to the ocean, as some other cities are.

Wu explains that a flood in the Schuylkill River, for example, is more likely to affect just the river’s walking trail rather than a large residential area.

Given the city’s relatively low exposure to projected floods, planners such as Wu expect to defend specific infrastructure that is seen as vulnerable rather than building resiliency across wide areas of the city.

“The way the city is approaching it is to recommend an asset-by-asset screening,” she says.

Wu said her office expects to release its first report on climate adaptation in October.

Nationwide, planners are looking beyond the traditional sources of government funding and toward public-private partnerships to fund much-needed infrastructure improvements, and private partners are shifting toward seeking stability and social improvement and away from the traditional search for the highest returns, says Anthony Kane from the Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure.

“Even private investors without a social or environmental motive are starting to realize that unsustainable infrastructure investments have a higher risk,” Kane says, “and they are building that into their frameworks.”