story by Liz Pacheco| photos by Albert Yee

After several years of explosive growth, Pennsylvania’s solar industry is in trouble. The same legislation that initially encouraged the fledgling industry now threatens to cripple it. While current lawmakers have proposed a solution, not everyone agrees that the solar industry deserves to be saved. Is the sun setting on our solar future?

After several years of explosive growth, Pennsylvania’s solar industry is in trouble. The same legislation that initially encouraged the fledgling industry now threatens to cripple it. While current lawmakers have proposed a solution, not everyone agrees that the solar industry deserves to be saved. Is the sun setting on our solar future?

Like crops awaiting harvest, solar panels fill the field across from Longwood Gardens’ Route 1 entrance. The array is impressive; 6,669 ground-mounted panels over nine acres. Although much bigger than corn stalks, the panels aren’t intruding on the landscape. They rise and fall, following the curves of the bowl-shaped field.

The company hired for the project originally wanted to level the field and, in all likelihood, would have put down asphalt and gravel. “We wanted to find and contribute to a new aesthetic standard for solar fields and installations,” says Paul Redman, director of Longwood Gardens, a nonprofit horticulture center in Kennett Square, Pa. “We developed an experiment to look at seed mixes that would establish low-growing, slow-growing native vegetation that could be planted in and around and among solar panels,” says Redman. Once the plants grow, the panels will appear to be floating in a meadow.

Paul Redman, Director of Longwood Gardens, has outlined a long-term solar plan for the nonprofit. The 1.5 megawatt solar field is only the first phase.Longwood first started exploring solar panel options almost five years ago. After two years of research, they announced a two-phase plan to install three megawatts of solar energy by 2018 — on a sunny day, these panels, in addition to Longwood’s long-term commitment to energy conservation, would satisfy 100 percent of their energy needs. In June 2011, 1.5 megawatts of solar energy (via the 6,669 panels) was installed, enough to supply 30 percent of the Gardens’ current energy needs.

Paul Redman, Director of Longwood Gardens, has outlined a long-term solar plan for the nonprofit. The 1.5 megawatt solar field is only the first phase.Longwood first started exploring solar panel options almost five years ago. After two years of research, they announced a two-phase plan to install three megawatts of solar energy by 2018 — on a sunny day, these panels, in addition to Longwood’s long-term commitment to energy conservation, would satisfy 100 percent of their energy needs. In June 2011, 1.5 megawatts of solar energy (via the 6,669 panels) was installed, enough to supply 30 percent of the Gardens’ current energy needs.

But Longwood’s goal of 100 percent solar energy is in jeopardy — as is Pennsylvania’s entire solar industry. The Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard Act of 2004, the law that determines how much solar our utility and electric supply companies are required to buy, is no longer encouraging new solar projects. Solar advocates have introduced legislation in an attempt to restructure the law’s requirements and keep the industry viable. But critics of the bill — largely consisting of fossil fuel advocacy groups — believe it unfairly favors one energy source over another.

So, what’s at stake?

Without supportive legislation, Pennsylvania’s leadership in renewable energy is threatened, and with it the nearly 5,000 jobs created by our state’s solar industry.

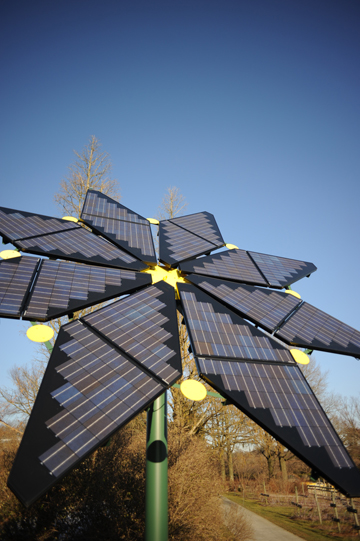

Visitors to Longwood Gardens can learn about the new solar field from a demonstration flower installed in the idea garden.The Boom

Visitors to Longwood Gardens can learn about the new solar field from a demonstration flower installed in the idea garden.The Boom

Five years ago, Pennsylvania had only 300 solar energy systems. Today, there are more than 5,600. The explosive growth is part of a national trend — one partially driven by tax incentives, and rebate and grant money from states and the federal government. When the economy collapsed in 2008, Pennsylvania introduced $180 million in funding for solar. At the same time, the federal government introduced $11 million in stimulus grants and a tax incentive program.

But the issue so hotly debated right now involves legislation passed under former Gov. Ed Rendell. The Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard Act of 2004 set requirements for how much renewable energy utility and electric supply companies are required to buy. By 2021, 18 percent of Pennsylvania’s energy must come from renewable sources. Of that 18 percent, only one half of a percent must come from solar. (The rest comes from other renewables, including wind, hydro and geothermal.) While solar requirements are different in each state, Pennsylvania’s are small compared to our neighbors. In Delaware, the overall renewable energy requirement is 20 percent by 2019, with four percent from solar; New Jersey’s is 22.5 percent by 2021, with two percent plus an additional 5,316 gigawatts from solar.

“The credit program, as we initially established it back in 2004, was designed to gradually push the amount of solar on an annual basis a little higher,” explains Rep. Chris Ross, R-Chester, who helped create the state’s solar requirement. “[The act] wasn’t going to shock the ratepayers by creating a substantial shortage, but was just going to persistently nudge the solar installations in Pennsylvania forward.”

While Pennsylvania’s solar requirements were considered aggressive at the time, the policy really was very conservative, says Ron Celentano, a solar engineer and consultant at Celentano Energy Services who helped develop the solar standard. “We didn’t want to have a requirement higher than what could be met because there would be penalties,” he explains. And at the time, “Pennsylvania never had any kind of grant or rebate for pretty much anything.”

After 2004, when the market changed and funding increased, Pennsylvania’s solar industry was in an incredible position to grow. “We had a nice, perfect storm,” explains Kristin Sullivan, the energy manager for the City of Philadelphia and director of its Solar City America program. Suddenly, the solar industry was booming.

The Money Maker

To fulfill the state’s solar mandates, utility and electric supply companies don’t install solar panels; they purchase solar renewable energy credits, or SRECs. When a person or business installs solar panels, they generate electricity that reduces their electric bill. Simultaneously, they’re generating energy credits utility companies are required to buy. “[SRECs are] basically a commodity and they have value because of the fact that you generate electricity without creating emissions,” explains Celentano.

In Pennsylvania, the SREC market has changed dramatically. “When we started [the Longwood] project, the [SRECs] were at a value of around $265,” says Redman. “And by the time we commissioned and flipped the switch on this project, I think they were at $155.” As of February 2012, an SREC in Pennsylvania costs $35. Comparatively, an SREC costs $205 in New Jersey, $285 in Ohio, $60 in Delaware and $540 in Massachusetts. The low SREC price was made worse by another factor: no more third-party support. By the end of 2011, the state rebates were nearly depleted, the federal grant program had expired, and the tax incentive changed from a cash grant to a tax credit.

A state’s portfolio standard dictates the SREC market. Although Pennsylvania’s solar requirement is small, those creating the policy didn’t think the industry would grow as fast as it did. “Subsequently, we have three times more SRECs available on the market than the regulations require,” explains Andrew Kleeman, senior vice president of new markets at Mercury Solar Systems. Kleeman is also founder of Eos Energy Solutions, Philadelphia’s largest solar integrator before it sold to Mercury in 2010. “And as simple supply and demand would dictate, the price of those SRECs has collapsed. So not only did we lose the state and federal subsidies, we also lost the long-term subsidy of SRECs because they’re worth almost nothing today.”

The Stall Out

A view of the solar field at Longwood Gardens.For Longwood, the collapsed SREC market doesn’t affect the first phase of their solar installation. They have a Power Purchase Agreement with EcogySolar, which means the company owns the solar equipment and in turn, sells the power produced back to Longwood. EcogySolar, not Longwood, is impacted by the SRECs’ reduced value. But this means the next installation of 1.5 megawatts could be delayed. Although targeted for 2018, without a third party to buy the SRECs, the next phase can’t go forward.

A view of the solar field at Longwood Gardens.For Longwood, the collapsed SREC market doesn’t affect the first phase of their solar installation. They have a Power Purchase Agreement with EcogySolar, which means the company owns the solar equipment and in turn, sells the power produced back to Longwood. EcogySolar, not Longwood, is impacted by the SRECs’ reduced value. But this means the next installation of 1.5 megawatts could be delayed. Although targeted for 2018, without a third party to buy the SRECs, the next phase can’t go forward.

Projects across the state are facing the same challenge. In Philadelphia, the Water Department had proposed installing a three-megawatt system on top of water storage basins. (The Water Department even planned to use Longwood’s seed mix experiment.) Originally, more than 45 solar developers were interested in partnering with the Water Department. Only three submitted proposals. With SREC prices spiraling further downward, the city would have had to take on significant risk to make the project viable. “The city intended to buy the electricity and the SRECs would go to a third party. But at such low prices, the economics just weren’t working,” says Sullivan. “It would not have been the best use of taxpayer dollars.” The Navy Yard and the University of Pennsylvania have also put their solar plans on hold.

The Waiting Game

Since the SREC market crashed and the monetary support from the state and federal governments ended in 2011, the Pennsylvania solar industry has practically ground to a halt. “It’s quite clear and it already has been happening that we’re losing jobs,” says Ross. “And we’re certainly losing an opportunity to take advantage of solar installations.” Some solar businesses have laid off workers, others have “just [moved] to other states, like Massachusetts, to do work. Or they’ve just closed shop,” says Celentano. “They just can’t do it.”

While the Standard Portfolio Act is too complicated to change (for now), those in the industry are looking to shift the law’s timeline. They’ve proposed House Bill 1580, which was formally introduced by Ross last October. The bill would increase the solar requirement for 2013, 2014 and 2015 and then lower the requirements in later years. Pennsylvania would still reach the same half percent required by the standard portfolio. The bill also proposes closing the Pennsylvania borders to restrict SREC purchases to in-state projects — something other states, like New Jersey, have been doing for years. As the legislation currently stands, Pennsylvania accepts SREC credits from out-of-state projects, and this drives their value down further.

Both Kleeman and Celentano were very involved in creating this bill and they see it as the only way the solar industry can be saved. “If this bill doesn’t pass, the incredible industry that Pennsylvania built on prudent investment, both private and public sector, is gone,” says Kleeman. Even multi-state or national companies, like Kleeman’s own Mercury Solar Systems, would be less likely to invest in Pennsylvania. “The same amount of investment in another state just yields a higher return,” he explains.

When first introduced, the bill had more than 100 co-sponsors in the state’s House of Representatives and a companion bill has since been introduced in the state Senate. But before 1580 can be voted upon, it has to pass through the House Consumer Affairs Committee. Those against the bill, like the state’s Chamber of Business and Industry and the Energy Association of Pennsylvania, have cited three main arguments against its passing: the solar industry shouldn’t be given a “bailout”; the changes will cost ratepayers too much money; and closing Pennsylvania borders to SREC credits violates the Constitution’s Interstate Commerce Clause.

While the commerce clause could technically be violated under the bill, other states like New Jersey have closed their borders without being challenged. And Kleeman, Celentano and others don’t see 1580 as a bailout, but a fix to the supply-demand relationship. They estimate the cost to ratepayers to be, at most, four cents a month. The Energy Association of Pennsylvania, the trade association that represents electric and natural gas utility companies, doesn’t agree with this estimate.

“We think [1580 will] raise the bills of customers for years to come,” says Terry Fitzpatrick, president of the Energy Association. “And we’re concerned about that because there are other things that have to be paid for.”

Fitzpatrick has been one of the leaders against 1580 and has raised questions about its ability to truly “fix” the market: “What happens if this doesn’t work? What if the credit prices don’t go up enough? Is this industry going to come back again for more money because the credits still aren’t worth what they want?” What Fitzpatrick doesn’t consider is the potential for solar to reduce the bills of all ratepayers.

“[Solar energy] actually suppresses the cost for the ratepayers at times of peak power,” says Ross. With additional solar energy supplementing the grid, it’s no longer necessary to turn on a more expensive, less efficient plant.

Advocates view this bill as necessary to keep renewables in the state. Those against 1580 see it as an unnecessary concession to the solar market.

“They feel that the government shouldn’t be stepping in and helping the industry,” says Celentano. “[But] they’re obviously giving a substantial favor to the fossil fuels industry.” The Energy Center at PennFuture, a leading environmental advocacy organization, released a study in December 2011, citing fossil fuel subsidies for coal, oil and natural gas to cost Pennsylvania taxpayers $2.9 billion per year. But even this number doesn’t lend much transparency to the issue.

“There are certainly fewer state business assistance programs today than there were a few years ago,” explains Gene Barr, president of the Chamber. Barr, like Fitzpatrick, is against the bill. He doesn’t want to favor the solar industry, although he recognizes the importance of renewable energy. “We certainly support the development of solar technology, wind technology, all energies,” he says, “because we’re going to need all those energies coming out.”

So where does the solar industry go from here? If the bill makes it through the committee, there’s a strong chance 1580 will pass in the House and Senate. But time is running out. The government’s calendar year ends May 31 and after that, the bill will have greater difficulty coming to a vote. In the meantime, projects like Longwood’s are delayed. “Right now, to be honest with you,” says Redman, “we’re really not doing anything.”

Pennsylvania solar advocates are hoping to convince the House Consumer Affairs Committee to vote on 1580 when the legislature reconvenes in mid-March. Pennsylvania residents can contact House Majority Leader Mike Turzai at 717.772.9943 to express support for bringing the bill to a vote.