Bernard Brown wants to introduce you to your neighbors. Not the human ones, but the flora and fauna that surrounds, or is accessible to, us city dwellers.

Brown, a longtime contributor to Grid, has been working the “Urban Naturalist” beat since 2009.

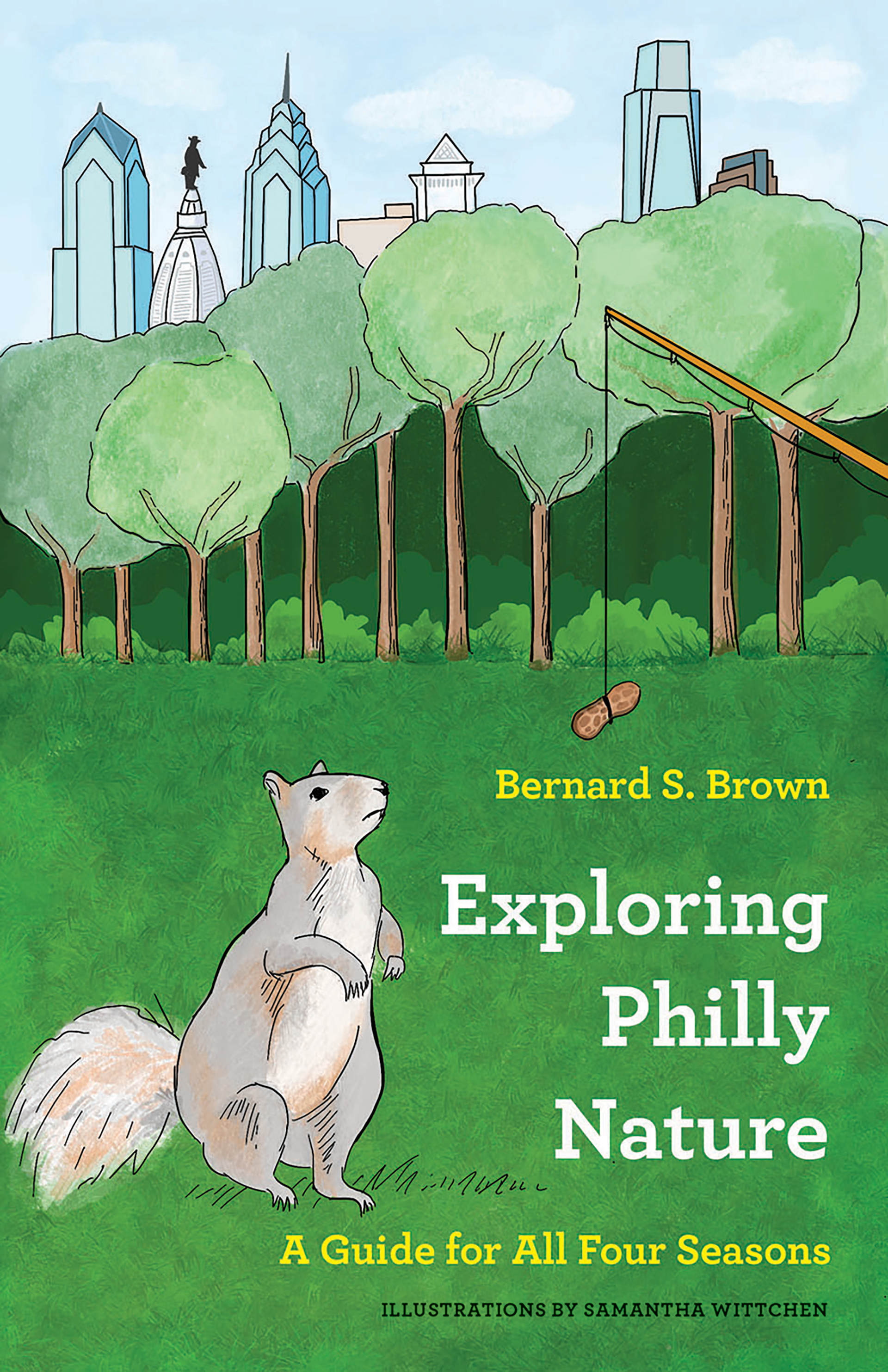

His first book, “Exploring Philly Nature: A Guide for All Four Seasons,” offers 52 invitations, one for each week of the year, to experience wildlife in familiar and unexpected places. All chapters have an accompanying illustration by sustainability consultant and fellow Grid contributor Samantha Wittchen.

If you haven’t had the good fortune to read Brown’s illuminating and entertaining contributions, it’s understandable if you ask: Hasn’t wildlife been essentially exterminated in major urban areas such as Philadelphia? Aren’t the squirrels, rats and cockroaches all that remain?

“You’re not entirely wrong,” Brown says, but though they are covered in concrete and asphalt, and roads prevent animal movement, cities have a lot more biodiversity than, say, farmland devoted to soy or corn. “When you get down on your hands and knees, you see a decent variety of plants.”

Sometimes “Exploring Philly Nature” leads you to natural places you might know, like Bartram’s Garden, The Woodlands Cemetery, the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum or the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education. But sometimes there are discoveries to be made in your basement, or a crack in the sidewalk. “Everywhere is habitat, and habitat is everywhere,” Brown writes in the introduction, and that is the primary message of the book. Even when you are indoors, you are in nature.

“Exploring Philly” is a slim volume, designed to be easily digestible, but there is a philosophical underpinning to the book, and it’s about attention. Where you direct your attention is going to affect how you experience life. Brown is imploring us not to miss the opportunity to connect to the place where we live and the life forms we share it with.

You can hear a birdsong — or it can be a Baltimore oriole, or a wood thrush. You can see flowers — or you can see Philadelphia fleabane, or white snakeroot. “As you learn more about the components of those landscapes, it makes it so much deeper, and so much richer. Your brain can give them names, and figure out what they are.”

“Then you’ve got a story,” Brown continues. “You can learn about each one of these things. Every species, every plant, every animal, every mushroom, has a natural history, and it has a story behind it. It’s kind of like looking at a bookshelf. Instead of just being like a bunch of vertical objects with writing on the spines, you’ve read these books.”

“And all of a sudden,” Brown says, “your walk down the sidewalk is that much more interesting every day.”

There’s a wide variety of plants and animals you can find using the book, including frogs, turtles, spiders and dog vomit slime mold (“one of the best names in all of nature,” in the author’s opinion). Just as helpful, though, is the ecosystem of communities and clubs that meet to explore nature together. For example, if dog vomit slime mold has piqued your interest, Brown recommends meeting up with the Philadelphia Mycology Club to go for a fungus-themed walk.

Through the years he says he has made some of his best friends in this circle of naturalists, and he places a high value on the camaraderie of fellow explorers. “You can still always go out birding by yourself and avoid crowds if you want, but it can be a very social thing where you can go out and find other people birding and stop and ask them, ‘Hey, what are you looking at?’”

Brown’s evolution into an urban naturalist was not pre-ordained. Unlike his parents, Brown was always drawn to the outdoors, and he got his first pet snake when he was a seven-year-old living in Columbus, Ohio. He continued to collect reptiles and snakes until he went to college at Wesleyan University in Connecticut and decided to sell his collection.

After completing graduate school at Johns Hopkins University, he moved to Atlanta for a stint with AmeriCorps, and he resumed collecting snakes. But things changed in 2004 when he moved to Philadelphia. Suddenly, discovering animals in their natural habitat seemed far more interesting.

“I think that the key shift was going from somebody who was really into keeping and breeding reptiles and amphibians as a hobby to someone who got much more interested in encountering them in the wild.”

Then, in 2009, he began writing for Grid and was tasked with documenting the natural world in the city.

Exploring Philly Nature was a lot of fun to write, because it’s all the recommendations I’ve been giving out informally over the years.”

— Bernard Brown

“[My wife] talks about how she misses being in school. She loved college. And I kind of feel like I still am [in school]. Every month I have to research and produce a paper.”

After all these years, it seemed to Brown like it was time to gather all of that knowledge in one place and write a book.

“‘Exploring Philly Nature’ was a lot of fun to write, because it’s all the recommendations I’ve been giving out informally over the years.”

Regular readers of Grid will also recognize Brown’s name from the investigative journalism he’s been producing around open spaces, including the City-sanctioned deforestation of Cobbs Creek and the South Philly Meadows. While Brown encourages us to have our radar raised so we can appreciate nature all around us, how does it feel for Brown to witness the wholesale destruction of larger areas of habitat?

“I’m going to quote Aldo Leopold, a famous ecologist, who wrote ‘A Sand County Almanac’: ‘One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.’ You’re always recognizing what has been done and what’s being done to the stuff that you care about. I think it’s hard to be optimistic, sometimes, but I would say that the long view can help.”

Two things in particular help to keep Brown’s outlook positive, and the first is how quickly nature recovers.

“Cobbs Creek is a great example, or the Wissahickon. Mills used to be up and down the creeks everywhere. The trees would have been cut down, cleared multiple times for firewood or building. Yet you can walk in there now and feel like you’re in the forest primeval or something. But it’s really a young landscape in the grand scheme of things, which means that eventually we can end up with something good again.”

The other comfort is how communities have rallied around when places they love have been taken from them.

“Cobbs Creek was an example. That golf course, it slipped through in a very secretive way. And there are a lot of people who would prefer not to see a golf course there. People who live in the neighborhoods, regardless of their race and class, have gotten upset about these things and oppose them. [The destruction] can be demoralizing, but there are reasons to moderate your disappointment. We’ve got a community of folks that we can pull together to be more active in the future.”