For a few years now, I have been avoiding writing an article about freshwater mussels like the one Kyle Bagenstose wrote for this issue. His article airs doubts about the claim that restoring native freshwater mussels can help clean polluted waters — just as efforts are ramping up to breed and reintroduce mussels to our creeks and rivers.

Up until now, I have found it convenient to avoid the doubts. Even if they don’t improve water quality very much, there are plenty of other good reasons to restore mussels to waterways where hundreds of years of dams and pollution have wiped them out, but I worry that not everyone will agree.

There are close to 300 species of freshwater mussels across the continent. More than a dozen are native to the Delaware River and its tributaries (many with fabulous names, such as the tidewater mucket and the alewife floater). They live for decades, filtering tiny bits of plant or animal matter out of the water.

Mussels are also intimately tied to the fish that swim freely around them. Non-tidal rivers and creeks only flow in one direction, which makes it impossible for the sedentary mussels to move upstream on their own. They have evolved what are essentially fish lures that draw in their free-swimming neighbors, at which point the mussels eject their minute babies. These then latch onto the fish’s gills. The wee mussels later drop off and settle onto the bottom, some of them now upstream from their parents.

All of this should be amazing enough to justify efforts to restore mussel populations, but the sad truth is that we too rarely appreciate the natural world for its own merits — and this is especially true for humble, uncharismatic creatures like mussels, whose fantastic lives unfold completely out of human sight.

So how do you convince public officials and foundations to spend money for mussel restoration? You focus on what they can do for us, their “ecosystem services,” in conservation lingo. And so mussel advocates point to water filtration. Mussels of course feed by pulling particles out of the water. Each mussel is small, but millions of them presumably add up to a river-scale water filtration system. The problem is that the science doesn’t back up that presumption, as explained in a paper co-authored by one of the experts interviewed in Kyle’s article.

But who cares? Is a little bit of exaggeration a problem if it serves the greater good of restoring native species to their habitat? Kyle’s article discusses why it may indeed be a problem.

Mussel restoration isn’t unique in this way. Advocates understandably promote valuable environmental initiatives using all the angles available, and it is understandable that they would avoid scrutinizing the shakier points. I don’t blame them. It shouldn’t be so hard to rally support for the environment, but it is.

So why didn’t I take on this subject sooner? As a nature writer and advocate for native biodiversity, I too have been content to avoid kicking the tires, particularly because I don’t want to erode support for restoring our historic mussel beds. It’s also personal. As a publication with a mission (it’s right there on our cover) we see ourselves as on the same team with anyone working for a more sustainable Philadelphia. These are people I respect and who, in many cases, I consider to be friends. Who wants to upset their friends if they can avoid it?

But here at Grid it is our job — and my job — to be more thorough than that, and to confront important questions about solutions that might not be so straightforward.

![]()

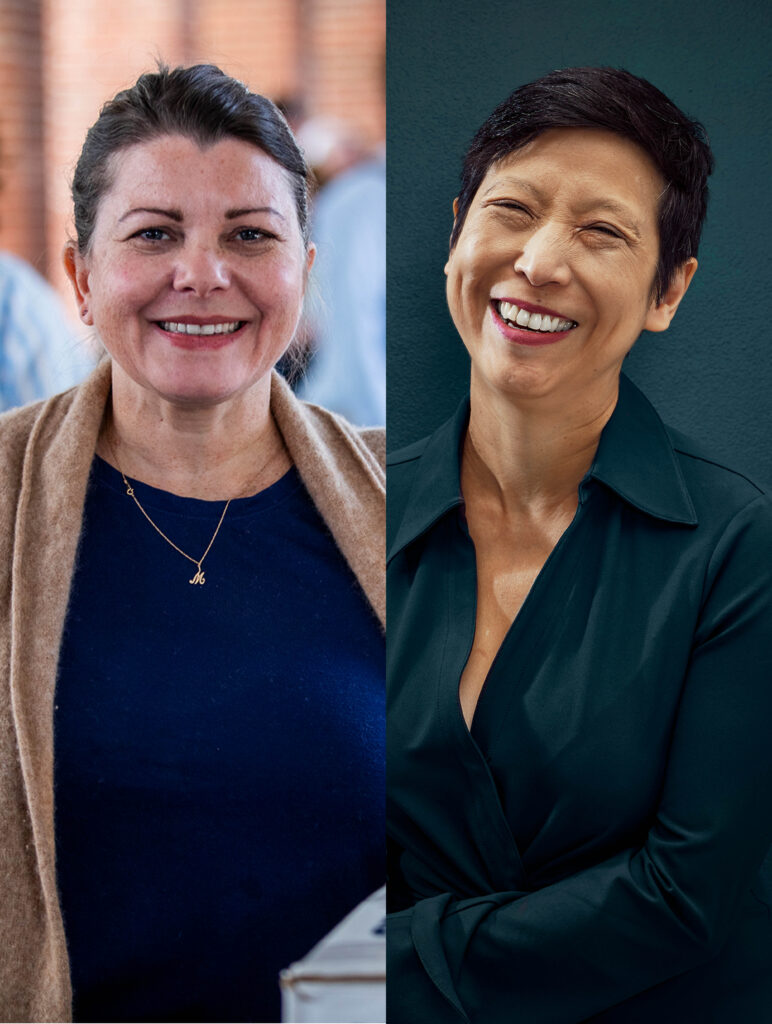

Bernard Brown, Managing Editor