On yet another wet weekend, a group of ten braced a downpour to walk along the trails of Strawberry Mansion’s Discovery Center for a wild plant tour.

Their journey began at the trail entrance, where an innocuous weed was growing. Tour guide Lady Danni Morinich, a local herbalist and forager, identified the plant as yellow dock and shared that it was also edible. Foragers passed around a bit of the leaf to munch on, a daring start to the rest of the morning.

Offered a bite, one teen quickly shook their head, wary. “Just wait until the apocalypse,” Morinich replied to resounding laughter, partly joking but partly warning of a possible future when such plant knowledge is necessary.

The walk was part of one of many programs organized by fellows from the Alliance for Watershed Education of the Delaware River (AWE), a coalition of environmental education centers increasing their collective impact in the watershed, this summer. The fellowship assigned 17 young adults to different centers to develop a project that would lead to increased engagement in the protection of waterways and parks. Some fellows created park toolkits with interactive games and guides, while others, such as Charlotte Spence and Jayla Clark, focused on urban botany. Spence and Clark’s projects gave community members a hands-on opportunity to access useful plant knowledge and foster connection to nature in urban environments.

Catalogs That Connect

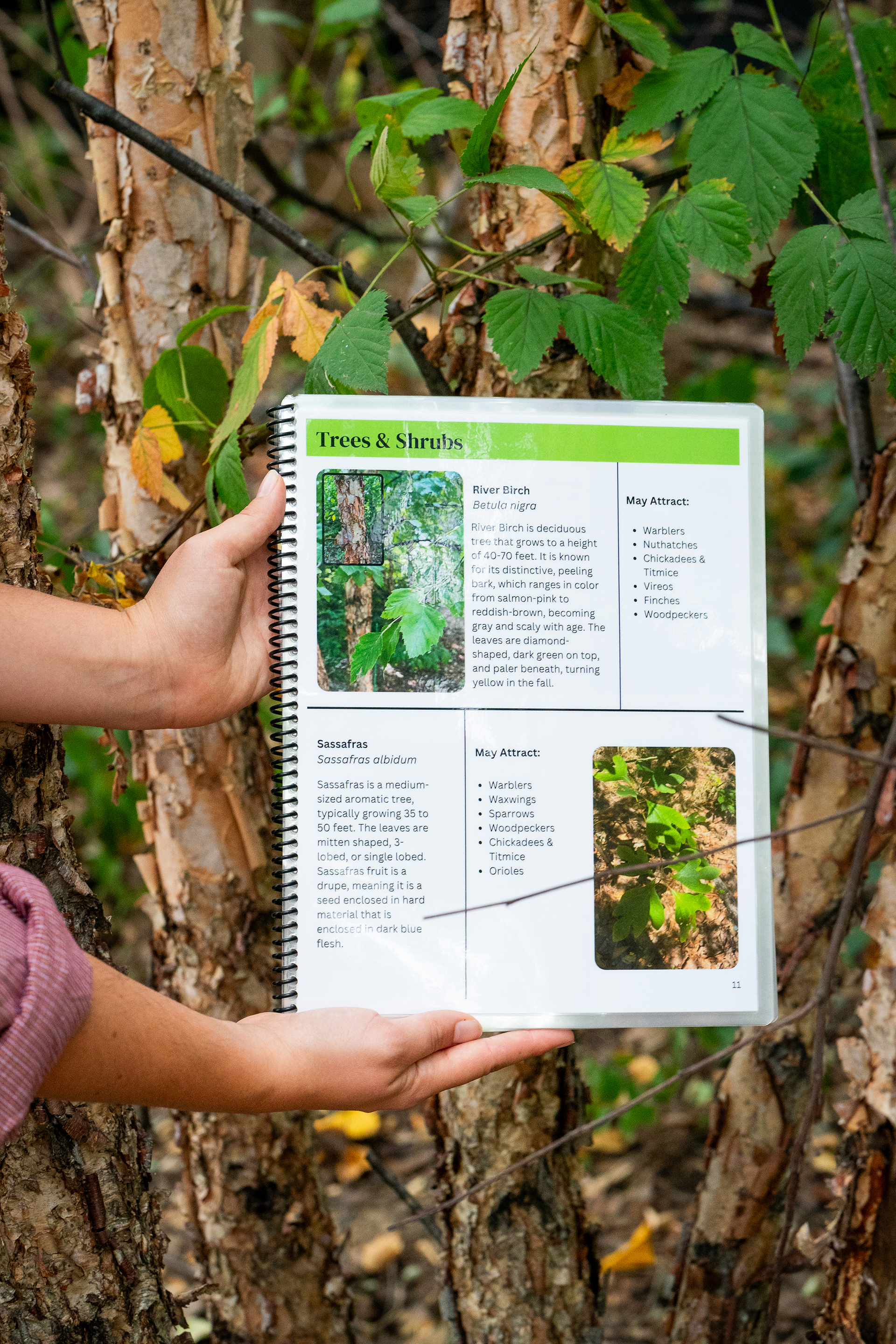

Berries that taste like Hawaiian Punch, natural antiseptics and treatments for sunburns are just a few of the things you can find on the grounds of the Discovery Center — and Spence is determined to identify as many useful plants as possible. Working alongside the Audubon Mid-Atlantic, she documented plant life at the center to create a field guide as the capstone project for her fellowship.

“Native plants are a crucial part of watershed conservation,” Spence says. “They have natural filtration, prevent flooding and bank erosion, and provide crucial habitats for birds and pollinators.”

“My Native Plant Field Guide” includes an introduction about native plants’ importance and ecological benefits, and an identification guide to different species with physical descriptions, photos and lists of pollinators the plants attract.

For Spence, 22, it was a full circle moment. When she was child, her mother found an old Audubon Society native plant pocket guide; Spence says she claimed it as her own and filled the pages — even though she didn’t yet know how to write. Underneath the depictions of flowers were the colorful scribbles of a budding botanist.

Her path solidified in high school as she began participating in climate justice activism and later pursued a degree in environmental studies at Oberlin College in Ohio. “I’ve been slowly trying to figure out how to put these passions to work,” Spence says.

Connectivity and community is the cornerstone of environmental work.”

— Charlotte Spence, AWE fellow

The AWE summer fellowship seemed to be a step in the right direction as it wedded Spence’s interests in urban sustainability, greenspaces and collaboration. “Connectivity and community is the cornerstone of environmental work,” Spence says. “I wanted to be part of a program that emphasized that connectivity between all these different environmental centers that had similar goals.”

Spence offered workshops to help people engage with the guide. She taught how to make native seed and clay soil balls that can be tossed anywhere to spread native plants; hosted a wild plant tour with Morinich; and offered a class on cooking with Japanese knotweed, an edible invasive plant that can also be used to make paper and ink.

“Just because it isn’t native and beneficial to these specific environments does not mean it doesn’t have abundant beneficial qualities,” Spence says.

During the educational walk with Morinich, she warned of the influx of AI-generated foraging books, often filled with dangerously wrong information. In a time where misinformation is rampant, the need for verified catalogs of what’s growing around us and their properties is becoming increasingly important.

Steve Miller, a Brewerytown resident, is an avid birder who relates the experience of birding to that of foraging and plant identification.

“One of the things that birding taught me is the abundance of life that is around you at all times. Going on this walk and learning about the other things that are out there while I’m out birding will make the experience even more interesting,” Miller says.

Sowing Seeds of Sentimentality

At the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education, Clark, 19, combined botany with art. Clark grew up nearby the center, visiting and volunteering for years, and considers it “a second home.” This was her second summer as a fellow there.

“I always felt comfortable and happy when I was surrounded by nature so I feel like it’s my duty to protect and conserve and advocate for the kind of environments I love and want to see myself in,” Clark says.

For her capstone project, Clark led a plant-a-card workshop where she taught participants to make a plantable seed card from recycled paper. She cultivated sun, shade and container-friendly mixes that would thrive in different environments and included seeds for natives like spotted beebalm, foxglove beardtongue, bellflowers and milkweed.

“It was a way for me to merge my interest in art with environmental advocacy and sustainability, and my way of bringing that to the people who go to the Schuylkill Center and that kind of outreach to people who don’t.”

Clark reached out to local organizations that focused on engaging people of color in urban natural environments, such as In Color Birding and Black Girls with Green Thumbs. She says about 70% of workshop participants were people of color and about 50% were families — which was her goal.

“To introduce planting to families who aren’t accustomed to it and want to get their feet into planting, especially with natives,” she says. “As I’m becoming more experienced in this field, I’m realizing just how important it is that everyone is included in this fight and in this effort because it’s affecting everyone.”

Growing Towards the Future

Both Clark and Spence say the fellowship was an impactful experience.

Clark says she feels equipped with new knowledge in anticipation of returning to her regular educator position in the fall at the Schuylkill Center. Spence says it was challenging for her not to plant more natives; she recognized that maintenance would be the responsibility of someone else after the fellowship ended. “I wanted [the capstone] to be something that could survive on its own, without me,” Spence says.

A highlight for both fellows was meeting new people, both those well-versed in environmental issues and newbies. Clark is excited to potentially work with environmental artists and join like-minded collectives moving forward.

Spence says that interacting with the environment at the Discovery Center and engaging with people along the way has not only taught her more about plants, but also reciprocity.

“The way that I learn best is by being out here and constantly exploring different parts of the watershed,” Spence says. “And seeing how different parts of the system interact with each other and sustain each other taught me so much about local environments in Philadelphia and as a whole.”