Remember Andrew Yang from the 2020 presidential debates? The current election cycle has been so frightening that you could be excused for forgetting the crowded Democratic primary stages of 2020, but Yang gained some headlines for backing a universal basic income (UBI) proposal he called the Freedom Dividend. Under his proposal, every American adult would receive a monthly payment of $1,000 to help with bills, housing — anything.

You might take the “freedom” in the title as an empty patriotic gesture (à la freedom fries) but it actually referred to a core goal of the program. Today, most people don’t have enough money to take the time off they need to attend to basic social needs like caring for children or the elderly — all the work that no one pays for. Extra money might allow them to work less so they can spend time on what’s truly important in life. And as Yang’s website puts it: “Many Americans are stuck in the wrong jobs because of a need to survive.” Imagine everyone having the freedom to be picky about the work they choose. It sounds downright un-American, right?

In this issue, Dawn Kane writes about a basic income pilot in Philadelphia. The pilot looks quite modest to my privileged eyes. Participants get $500 a month, which, for the recipients, is a potentially life-changing sum. These income pilots are generally intended as a solution to severe poverty, but conservatives view them as a threat because they fear that “free money” will discourage work. Four states have banned basic income programs.

President Joe Biden quotes his father saying, “Joey, a job is about a lot more than a paycheck. It’s about your dignity.” Candidates rarely say we should simply give out-of-work Americans enough money to live well and let them figure the rest out for themselves. Politicians campaign on jobs. Biden talks about the dignity of work because it reinforces a core American belief that work is inherently noble, and that choosing not to work is undignified.

Astra Taylor, interviewed in this issue, argues this is basically a scam. Our mantras about the dignity of work keep us from noticing that most workers are driven by insecurity, by the specter of hunger and homelessness, of falling behind on loan payments, drowning in copays, their kids having to drop out of college. Our belief in the nobility of work keeps us from peeking behind the curtain at the wealthy people and corporations that benefit most from the vast excess that workers produce.

In Grid we routinely write about the environmental problems caused by that excess production: the 40% of food that ends up going to waste, the mountains of clothing we throw away, the lawns of turf grass that we grow for decoration, the toxic electronics designed to break (I could go on, and I have). It’s not like we couldn’t do with less stuff, and it’s not like we couldn’t stop coercing people to produce it.

Yang is not a lefty like me, to be clear. He claims that the Freedom Dividend would support a robust consumer economy since everyone would have more money to spend, whereas I (perhaps more like Taylor) hope that removing insecurity would permit a shift away from consumerism and toward seeking activities that truly make us happy. Either way, we both see that the malarkey about the dignity of work doesn’t serve the workers.

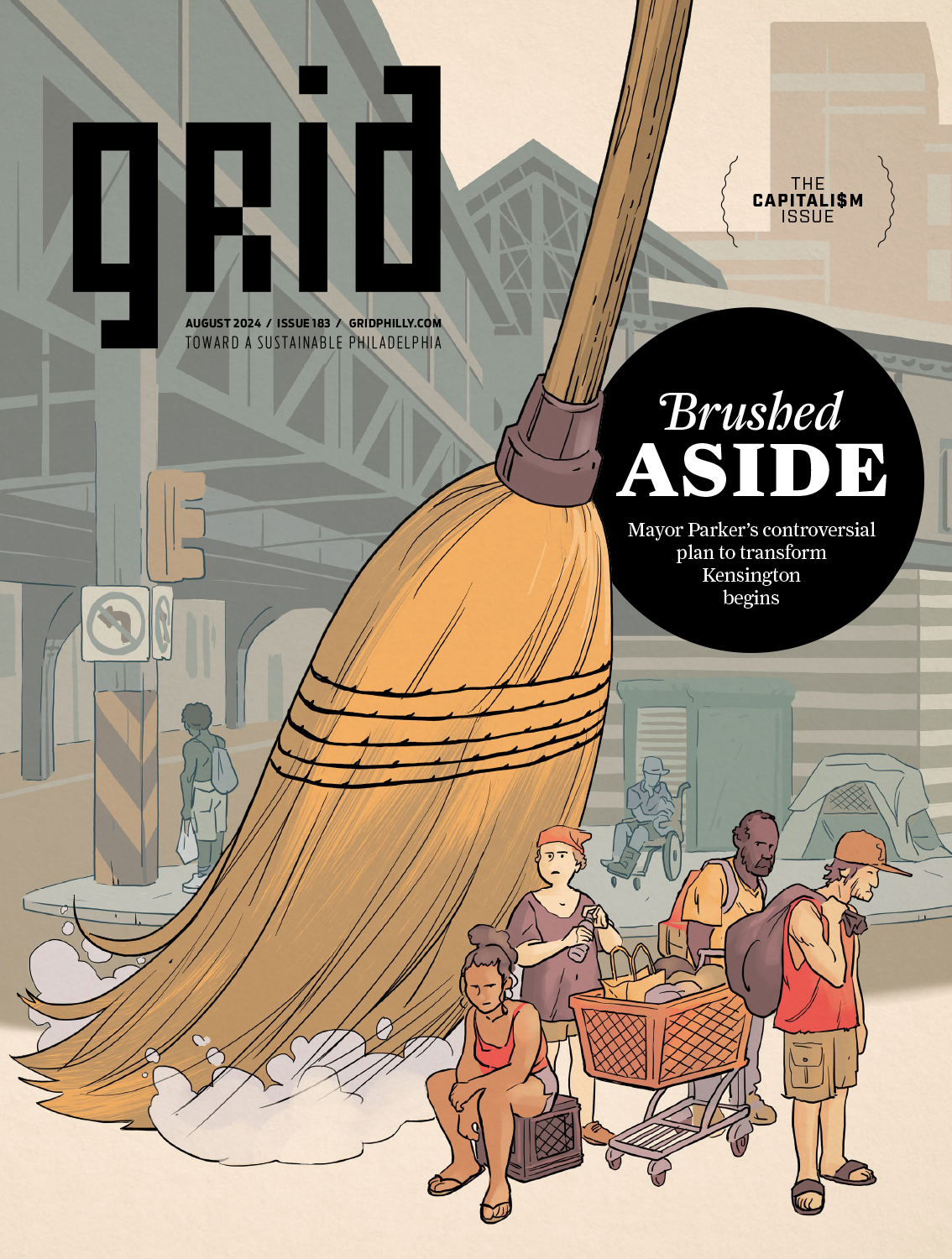

![]()

Bernard Brown, Managing Editor

Yes to this in a major way. I also ask the question “how much is enough?”

As a recovering tech industry return to art, artist in my mid 50’s – I see clearly that the push to be a good worker is all through our society and rethinking how we live is critical to our collective survival.

Would love to invite you to the 915 Spring Garden building were I’m imagining spaces that welcome this and other conversations as we develop re-emerging community and healing through art and movement.

@kellylawler555