By Kyle Bagenstose and Adam Litchkofski

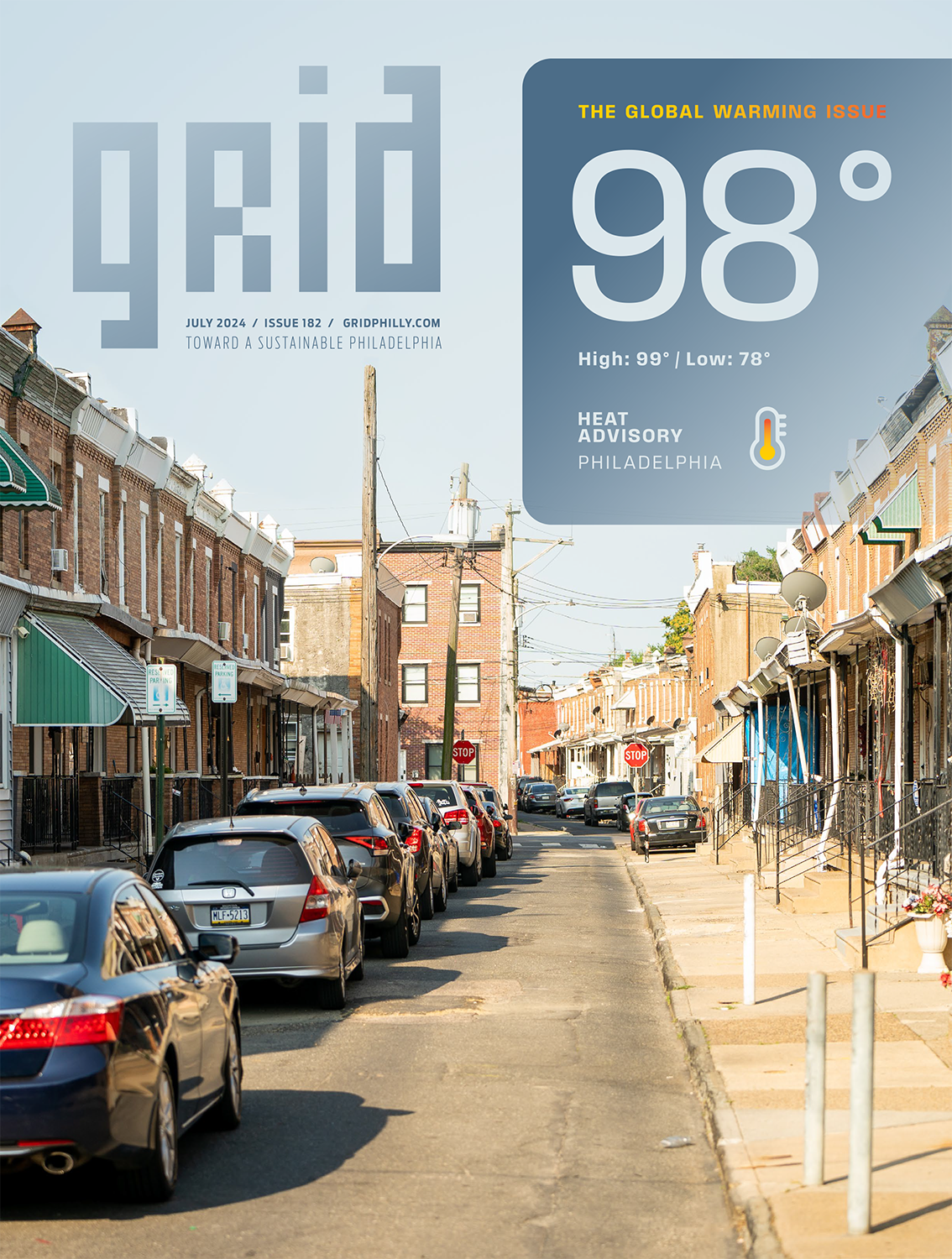

If you’re reading this story when it’s still hot off the press, odds are you’re probably pretty warm yourself. Another July has arrived in Philadelphia, and they ain’t what they used to be.

From 1939 through the end of the 20th century, Philadelphia’s average air temperature in this quintessential summer month was 77.6 degrees Fahrenheit, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In the 24 Julys since, only four have dipped back below that 20th century average, the last coming in 2009. Since then, the new mean is 80.7 degrees.

If that doesn’t make you sweat, try these statistics from the Philadelphia Office of Sustainability’s (OOS) Climate Action Playbook: In the 20th Century, Philadelphia averaged four days a year when the temperature exceeded 95 degrees. By 2100, it could reach 52.

Abby Sullivan, chief resilience officer for OOS, knows the danger well. She says that each spring, agencies across City government — from the Office of Emergency Management, to the Department of Public Health, to OOS — gather to prepare for the summer as members of the Excessive Heat Steering Committee.

“[Heat waves] are going to happen. So how can we best prepare to respond?” she says. “Everybody on the steering committee is aware of climate change, and that it’s making these events more intense and frequent.”

Across Philadelphia, there’s also a clear understanding of which residents are most vulnerable to the perils of a warming climate. A Heat Vulnerability Index maintained by the Department of Public Health combines ambient temperatures in different neighborhoods — which can range up to 22 degrees on the same day due to variables like tree cover — with statistics regarding asthma rates and elderly populations. It shows that heat risk is heavily concentrated in North, South and West Philadelphia; in communities primarily located away from parks and waterways; and where blocks are far less likely to have shade trees.

I would argue that the lack of street trees is just one example of the negative impacts of these racist practices, which left some communities more disinvested than others.”

— Jasmin Velez, Kensington Corridor Trust

As Jasmin Velez, a community organizer for the nonprofit Kensington Corridor Trust, points out, these same areas overlap with historically redlined communities.

“Environmental racism is a thing. These issues are seriously tied into social inequities and racism as a whole,” Velez says. “Where was the financial investment after redlining and white flight? I would argue that the lack of street trees is just one example of the negative impacts of these racist practices, which left some communities more disinvested than others.”

Sullivan says the City is working on a long list of measures to try to better prepare for climate change.

Her office is currently working to update the City’s climate science by applying new projections to a bevy of climate and resiliency plans and, for the first time, developing a guidance application that could help officials across City government make smart adaptation decisions.

“How do you choose the right temperature, or the right projection for precipitation, if you’re planning a road project that has a useful lifespan of 20 years, versus a drinking water facility that is going to be around for 100?” Sullivan says, adding that the guidance is currently slated to be released at the end of the year.

Specifically on heat, Sullivan says that her office plans to update its heat vulnerability assessment and is presently developing a request for proposal to “hone in” on what they want it to look like.

OOS has also received a $600,000 grant from the William Penn Foundation to spend two years engaging with Philadelphians to further identify heat adaptation solutions.

But when attempting to move beyond this data capturing phase and into the implementation of actual programs that could bring down the heat, the looming challenge is the same as it often is in Philadelphia: a lack of money.

I wish I controlled the purse strings. The scale we need to do this work at is really pretty staggering.”

— Abby Sullivan, Philadelphia Office of Sustainability

The Climate Action Playbook doesn’t provide an estimate of the dollars it will take to protect residents from our warming climate. Sullivan points to Portland, Oregon, where in 2018 residents voted to add a 1% retail tax to pay for a climate fund that invests in clean energy, public transportation and climate adaptation. Despite a shaky launch, The Oregonian reported last year, the fund is set to provide more than half a billion dollars for climate action for that city in the coming years.

But Philadelphia, Sullivan says, is hamstrung by a state “uniformity tax,” which preempts it from implementing similar taxes, such as progressive property tax that would tax wealthy homeowners at higher rates.

“I wish I controlled the purse strings,” Sullivan says, a hint of exasperation in her voice. “The scale we need to do this work at is really pretty staggering.”

Still, Sullivan says OOS is working with the City’s Office of the Director of Finance and a University of Pennsylvania Fels Institute of Government student to explore potential financial mechanisms that wouldn’t burden the average Philadelphian.

And, she says, the City has found some funding to get started on actual programs. The list starts — where else? — but with trees.

1. Grow Forest Grow

In 2023, Philadelphia Parks & Recreation released the Philly Tree Plan, a strategic plan for how to increase and maintain Philadelphia’s existing tree canopy. The topline goal is to increase the tree canopy cover to 30% in each Philadelphia neighborhood within 30 years, which would mark a major improvement over current conditions in broad swaths of North and South Philadelphia, where cover is currently less than 7%. In fact, Philadelphia is currently ranked last in tree canopy among major East Coast cities, according to a 2019 report from Parks & Rec, with less than half the cover of cities like Washington, D.C., and Boston.

With about $25 million per year in funding — currently less than 0.5% of the City’s annual budget — the plan says the City could plant enough trees by 2050 to prevent 400 premature deaths each year, reap environmental benefits worth $20 million annually and prevent $50 million per year in robbery and theft via an estimated 12% reduction in crime, drawing from a study done by the U.S. Forest Service in Baltimore.

However, current City funding levels are just a fraction of the amount needed to gain such transformations citywide. According to Charlotte Merrick, communications manager for Parks & Rec, the $25 million a year figure is envisioned as a “total of all spending from stakeholders, including the City of Philadelphia, nonprofit partners, private residents, commercial entities and development organizations, among others.”

While Philadelphia received a one-time $12 million boost to the program via a federal grant last year, the City itself only budgeted $1.5 million in the current fiscal year, which is set to receive a slight bump to $2 million in the first budget under Mayor Cherelle Parker. That puts a lot of the onus on nonprofit groups. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) Tree Tenders program supports about 80 volunteer groups citywide, planting more than 3,000 trees per year.

But without a robust, steady funding stream, especially for ongoing maintenance, overall progress feels tenuous. Once a tree is planted on a residential sidewalk, it becomes the financial responsibility of the homeowner. That can become an expensive liability, especially if the tree impacts their water or sewer line.

And recent history is discouraging: from 2008 to 2017, the city lost over 1,000 acres of tree canopy.

Still, advocates such as Asha-Lé Davis, a trees specialist for PHS, says the tree plan was a step in the right direction and opens the door to more robust action.

“Advocating to our lawmakers, writing letters to Council, showing up to Council meetings and getting involved that way is the first piece into making it known that [street trees] are a priority in this city,” Davis says. “As constituents, we have a lot of power.”

2. Beating The Heat, Block By Block

In 2019, the Office of Sustainability released “Beat the Heat,” a pilot project to build heat resiliency in Hunting Park, one of the city’s hottest neighborhoods. To date, it’s one of the most significant actions the office has taken to try to help residents deal with rising temperatures.

With funding from the Knight Foundation and Partners for Places, the initiative brought together City agencies, community groups and other stakeholders. Much of the effort was a fact-finding exercise: a survey of 600 residents revealed that 60% wanted to see more trees in Hunting Park, and 76% said better access to air conditioning units and fans would help them feel more cool in their homes.

It also revealed some serious problems. The survey showed that 77% of respondents said they often or always feel too hot in their homes. Only 40% had heard of programs to cut energy costs and help pay energy bills, and only 4% of those who reported not using air conditioning because of cost concerns said they had heard about utility assistance programs.

Sullivan says the information helped inform potential policy interventions. But five years on, it appears the parts of the program with the most potential to protect residents from heat in the short term have underwhelmed. Under a section in the 2019 plan entitled “Next Steps,” OOS first lists “continuing to implement” tree planting and other greening programs. Further down, it notes the planned launch of a “Hunting Park Heat Relief Network” that year, which provided a robust network of neighborhood cooling locations during heat waves.

I think what we found was that the people who are the most vulnerable to heat waves are the people who have the hardest times walking to community centers.”

— Allen Drew, local climate organizer

Allen Drew, a climate organizer involved with Beat the Heat, says such efforts to offer cool spaces in churches and other community centers didn’t really seem to move the needle.

“I think what we found was that the people who are the most vulnerable to heat waves are the people who have the hardest times walking to community centers,” Drew says.

However, Drew says a subsequent successful local initiative was held to collect and give away free air conditioning units to those in need. And while Sullivan agrees that cooling centers appeared to have limited utility, she says the experience helped OOS decide to focus on programs that keep people cool in their own homes. Her office plans to build on the lessons learned in Hunting Park as it moves forward; OOS is utilizing part of a $1 million U.S. Environmental Protection Agency environmental justice grant to perform a second neighborhood-level initiative in the coming years.

“We’re in the process of getting that project off the ground,” Sullivan says, adding they hope to identify the neighborhood by early 2025.

3. Innovative Ideas

Besides tree planting and community resiliency efforts, Sullivan says most of the Office of Sustainability’s heat mitigation efforts are still in the idea stage.

In the policy space, Sullivan says OOS is considering the development of regulations to protect workers from heat stress. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has announced efforts of its own, but Sullivan says her office is interested in local workplace protections to ensure adoption in a timely and effective fashion.

Cool pavement

• Sullivan says OOS is set to kick off a pilot “cool pavement” project at the Hunting Park Recreation Center. There, a material that reflects solar radiation will be applied to a 2,800-square-foot pathway used by both cars and pedestrians and evaluated for its effectiveness. Such solutions have already been used in cities across the Sun Belt, but Sullivan says City officials have questions about how it will hold up in the more variable weather conditions of the Mid-Atlantic before deciding if it should be more widely adopted.

“The concern is just how that material will perform with ice,” Sullivan says. “Will it be slicker than other surfaces? Will it degrade with ice? Will it degrade with salting?”

Cool roofs

• The City already has a Mayor Michael Nutter-era ordinance — with questionable enforcement — requiring all new construction to have “cool roofs” that reflect sunlight. But Sullivan says OOS is also looking into ways to potentially secure federal funding that would enable existing residences to get cool roofs at a steep discount, or even free.

Weatherizing and electrifying homes

• Harkening to the lessons of the Beat the Heat initiative, Sullivan says it is paramount to find ways to help residents stay cool in their own homes. As such, this summer OOS plans to launch a new “Energy Poverty Alleviation Strategy” to help find ways for residents to weatherize and electrify their homes, which can help them stay cool, reduce energy bills and ultimately lower their carbon emissions. The City already operates a Basic Systems Repair Program for homeowners, but Sullivan says the new program will focus on identifying funding sources like the federal Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 to help scale up such home improvements.

Adam Litchkofski is a journalism student at Temple University. Segments of this story originally appeared in a special project Litchkofski published on street trees.