One behemoth of a building in Eastwick looms large, both literally and in discussions about food recovery in Philadelphia. At 700,000 square feet — about 12 football fields — the Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market (PWPM) is the largest refrigerated structure in the world. Eighteen of the largest produce vendors in the Mid-Atlantic share warehouse space there. Business as usual produces millions of pounds of fruit and vegetable waste annually.

We’re wasting more than double — almost triple — the amount of food that’s needed to theoretically end food insecurity in our country.”

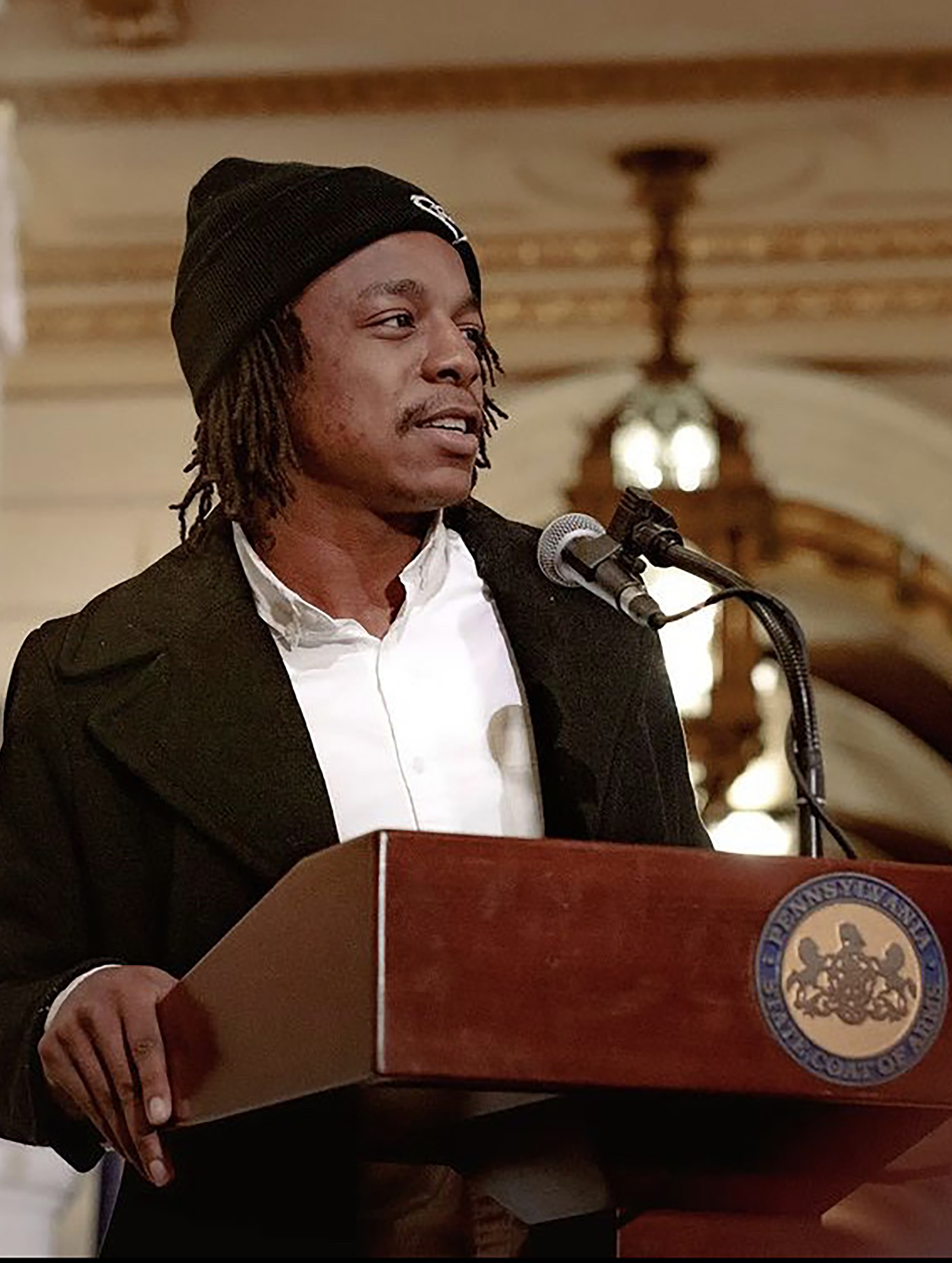

evan ehlers, founder of Sharing Excess Inc.

PWPM enters the food recovery conversation because it exemplifies both the potential and the precarity of our food system, and this juxtaposition suggests a strategy for addressing the twin challenges of hunger and food waste. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service estimates that between 30 and 40% of the U.S. food supply is wasted while almost 34 million people in the United States live in food insecure households.

“We’re wasting more than double — almost triple — the amount of food that’s needed to theoretically end food insecurity in our country,” says Evan Ehlers, founder of Sharing Excess Inc. Sharing Excess partners with grocery stores, wholesalers and farmers to rescue and redistribute on the order of 100,000 pounds of food each week.

“There is enough food,” emphasizes Megha Kulshreshtha, executive director of Food Connect, which helps scale existing food recovery efforts via technology solutions, last-mile logistics support and program management. “It’s a matter of our society having the right tools, technologies, systems and people to support getting that food in a timely way to those who need it.”

For all their lofty goals, Philadelphia’s food rescue operations had humble beginnings.

Kulshreshtha, whose parents came to the United States from India with three kids and $40, launched Food Connect in 2014 as a weekend passion project while holding down a day job as a portfolio analyst.

Sharing Excess got its start in 2018 when Ehlers, studying entrepreneurship at Drexel University, converted the semester’s-end surplus in his student dining account into ready-to-eat meals and spent a life-changing day distributing them in Center City. Before long he had commandeered his grandmother’s Hyundai to collect unspoiled but destined-for-the-dumpster foodstuffs from local grocery stores during downtime between classes.

Even Philabundance wasn’t always the multimillion-dollar force or household name it is today. Back in 1984, founder Pamela Rainey Lawler ran the fledgling food rescue singlehandedly out of her Subaru.

But oh, how times have changed! The pandemic “highlighted many of the existing gaps and vulnerabilities within our food ecosystem,” as Kulshreshtha puts it, and food recovery operations have expanded in the COVID-19 era to better meet the enduring need in what George Matysik, executive director of Share Food Program, calls “the hungriest big city in the country.”

Food Connect, for instance, has permanently added home delivery and multilingual technology options to the support services it offers. And Philabundance, serving nine counties in Pennsylvania and New Jersey as a member of Feed America’s nationwide network of food banks, currently feeds 140,000 people per week, up from 90,000 pre-pandemic.

For Matysik, March 11, 2020 stands out as the day when supply chain upheaval necessitated a “pivot toward rescuing more refrigerated and frozen products than ever before.” Share Food Program has built out its refrigeration and freezing capacity over the past few years, and its staff has ballooned to more than 70 since Matysik took the helm in 2019. The amount of food diverted from the waste stream by Philly Food Rescue has grown five- or six-fold since Share Food Program acquired the nonprofit in July 2021 and leveraged its infrastructure to extend their reach.

March 2020 was even more transformational for Sharing Excess. A front-page article in The Philadelphia Inquirer on March 17 brought unprecedented visibility to the new kid on the food recovery block, detailing efforts by Ehlers and his team to prevent food from pandemic-shuttered eateries from going to waste. “This news piece got us 100 volunteers to sign up and become drivers,” Ehlers recalls. “We really started to grow basically in the span of 24 to 48 hours.” Soon Ehlers had rented a warehouse in West Philadelphia and converted it into a food distribution center. As of September 2022, Sharing Excess had 29 employees, 11 of them full-time, and was deploying upwards of 400 volunteers to fulfill its mission of “using surplus to solve scarcity.”

Operations like Sharing Excess bring much-needed agility to food recovery efforts. “A lot of our logistics are set on systems or routines,” says Philabundance director of communications and marketing Chelsea Short, “so it’s not always easy for us to be able to jump to those immediate needs.”

Where perishable foods are concerned and viability windows are measured, as Kulshreshtha notes, in “minutes and hours, not days or weeks,” Sharing Excess’s ability to get a box of turkey sandwiches or a case of bananas from café to community center in 30 minutes or less is a game changer.

Unlike traditional 9-to-5, Monday-to-Friday food banks, “the food industry is a 24/7 operation,” says Share Food Program’s Matysik. “So we as nonprofits in this space need to be able to respond to both our clients and our food donors.”

Technology enables all this prompt ferrying of food. Philly Food Rescue uses the Food Rescue Hero app to coordinate collection and redistribution of surplus food, and Sharing Excess has developed its own open-source technology to similarly streamline logistics. It is possible in today’s smartphone age, says Kulshreshtha, to “schedule deliveries within a few seconds,” to “match thoughtfully,” and to “connect organizations and people in real time.”

The technology, of course, is just a tool, and of little use without the network of people it activates. “The most important things are our partnerships, our ability to actually go out and create these enduring relationships, and to pick up food and deliver every day,” says Ehlers.

Ehlers stresses, too, that the people receiving the diverted food are also critical to the responsive, round-the-clock food rescue campaign his and allied nonprofits are conducting. While 80% of the food Sharing Excess collects is distributed by other organizations, it also stocks community fridges and hosts pop-ups. One especially massive giveaway made headlines in October. In a three-day event dubbed “Avogeddon,” Sharing Excess handed out millions of surplus avocados — by the boxful — to Philadelphians thronging FDR Park. The messaging that accompanies these festive events, which often feature local musicians, is sometimes surprising to those partaking in the free food.

“Instead of charity this is more solidarity,” Ehlers explains. “This is thanking folks for being a part of a solution of helping us use food that would have otherwise gone to waste.”

Much less food is going to waste at the Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market these days. Sharing Excess personnel go through every box of to-be-discarded food, glean anything edible, and get it to the likes of Philabundance and Share Food Program — pronto.

And while PWPM may be the big prize, the big headline in food rescue success, Ehlers now has his sights set on more modest targets.

“We are really focused on this food business piece,” he says of his organization’s current goals. “How can we be the best possible solution so that no food business ever is deciding to [send] millions of pounds of produce to the landfill? It’s like the dumbest thing ever. Not only does it not feed people, but it’s also costing them so much more money than it would to just donate it.”