story by Liz Pacheco | photo by Gene SmirnovApril 1, 2012, 10:45 a.m. The line outside the Pennsylvania Convention Center was growing. Parents with strollers, young professionals, older couples, eco-conscious hippies and families in Phillies shirts were all patiently waiting for 11 a.m. Apparently the 1,100 pre-sold tickets were no fluke. The Philly Farm & Food Fest was attracting a crowd.

story by Liz Pacheco | photo by Gene SmirnovApril 1, 2012, 10:45 a.m. The line outside the Pennsylvania Convention Center was growing. Parents with strollers, young professionals, older couples, eco-conscious hippies and families in Phillies shirts were all patiently waiting for 11 a.m. Apparently the 1,100 pre-sold tickets were no fluke. The Philly Farm & Food Fest was attracting a crowd.

Inside, the 110 exhibitors were putting the final touches on their displays. Urban Apiaries opened jars of their Philadelphia-raised honey, Birchrun Hills Farm prepped pieces of their coveted Chester County cow’s milk cheese, and area favorite Lancaster Farm Fresh Cooperative set up an expansive local products tableau—haystacks included. Little Baby’s Ice Cream even brought in their freezer-toting tricycle to scoop homemade flavors like Earl Grey Sriracha and Cardamom Caramel.

The Philly Farm & Food Fest, a collaboration between Fair Food and the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture, saw nearly 3,000 people that afternoon. While attracting a few thousand attendees to a local food event may not seem remarkable nowadays, consider the food scene in Philadelphia 25 years ago. Eating locally meant a cheesesteak, not farm fresh vegetables. “Farm to table” wasn’t part of the restaurant vocabulary. And there weren’t regular (if any) farmers markets in the city. So, what’s changed? Why do Philadelphians support—and even expect—regular access to local foods?

For Judy Wicks, founder of the White Dog Cafe and Fair Food, the local food movement’s beginning was almost accidental. “[At the White Dog] I wanted the idea to be to serve what’s fresh and local,” she says. “But, it wasn’t because there was a trend or because I was trying to start a trend; I simply wanted to have what I had enjoyed myself.”

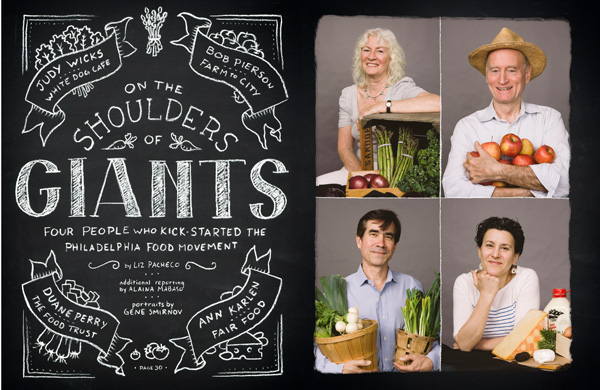

The White Dog opened in 1983, and has since been a cornerstone of the local food movement in Philadelphia. But Wicks isn’t alone in her efforts. Duane Perry, founder of the Food Trust; Bob Pierson, founder of Farm to City; and Ann Karlen, executive director of Fair Food, have all made significant contributions to building the local food community. While their individual efforts were influential, it’s their collaborative work that has made Philadelphia’s food movement so vibrant.

Creating a Truly Local Restaurant

At her home in Fitler Square on a warm April morning, Judy Wicks explains her evolution as a local food leader.

At her home in Fitler Square on a warm April morning, Judy Wicks explains her evolution as a local food leader.

“I grew up in a small town and my parents had a huge vegetable garden,” she recalls. “So, in the summertime, the three kids would go up and pick the vegetables, and we would eat from the garden all summer long. Then my mother and grandmother would can and jar for the winter… We also went to the farmers market all the time too… So, I kind of grew up with that kind of background.”

After 12 years at the French restaurant La Terrasse in University City, during which Wicks spent time as a waitress, general manager and, finally, business partner, she decided it was time to open her own restaurant. She moved her family to a Victorian brownstone in West Philadelphia and opened a take-out muffin store below. The menu of muffins evolved into soup and sandwiches, and eventually, a 200-seat restaurant known as the White Dog Cafe.

Wicks, who is not a chef, credits the inclusion of local, sustainable food sources on the menu to the restaurant’s first chef Aliza Green. While Green worked at the White Dog for just a year, she brought with her connections to local farmers and a desire to implement the new, California-style cuisine chefs like Alice Waters were using. “I hired Aliza because I wanted someone that knew how to buy from farmers,” says Wicks.

By 1986, the White Dog was sourcing produce from Mark and Judy Dornstreich’s Branch Creek Farm in Perkasie, Pa., and Glenn Brendle’s Green Meadow Farm in Gap, Pa. “[Brendle] was the first one to bundle orders where he would go around to other farms and pick up food,” says Wicks. “So, he was the first distributor, as well as a farmer.”

Soon after the White Dog started using local produce, Wicks learned about the inhumane treatment of animals that’s rampant in the meat industry. “My love of animals is really my driver,” she says, explaining how she pulled conventional meat products from her menu and began to explore this side of local eating.

By then, Green left to have her second child and sous chef Kevin Klause (now of FARMiCiA) had stepped into the executive position. Again, explains Wicks, it was the chef who headed the White Dog’s transition into sustainable food. “Kevin really did all that work,” she says. “I mean, he was the one that really researched where can we get the pork, where can we get the beef, and finding new farms and orchestrating all that.”

During the 1980s and ’90s, the White Dog became a springboard for many educational and sustainable food initiatives. The restaurant brought in regular speakers and hosted events like farm and community garden tours, a weekly Farmers Sunday Supper and the annual Dance of the Ripe Tomatoes—a street party celebration of sustainable and humane farming.

But for Wicks, it still wasn’t enough. “My big turning point was realizing that it wasn’t enough to have one restaurant doing all this stuff,” she says. “It wasn’t just about the White Dog. What we had to do was focus on the [food] system… and how could we build that system.”

Connecting Restaurants & Farmers

Typically, restaurants consider each other competition, not potential collaborators. Despite this, Wicks believed cooperation among restaurants was the key to building both a sustainable business and local eating community. She started the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies, the national parent organization for Philadelphia’s Sustainable Business Network, and in 2000 launched Fair Food—an organization that provides free consulting to chefs about using local foods. “I asked Kevin to just turn over the list of all our farmers,” says Wicks. “This might seem like common sense, but it’s really unheard of in business to give a list of your suppliers to your competitors.”

Already committed to various projects, Wicks hired Ann Karlen to lead Fair Food. Karlen was an ideal candidate; she had experience in starting a nonprofit (the artist collective Vox Populi) and interest in the food movement. And unlike many already involved in these issues, she didn’t have a farm or restaurant to run.

“In the beginning of my job, I sounded a lot like a door-to-door salesman,” says Karlen. “It was literally about going door-to-door, kitchen door to kitchen door saying, ‘Will you talk to me about buying from these local farms?’”

As Karlen began putting a system in place for farmers and chefs to do business together, the food movement was gaining steam on a national level. Food lovers were starting to recognize the benefits of local food, and restaurants were realizing the value these local products had. “[Restaurants] were the audience willing to pay a little bit of extra money for that product,” says Karlen. “They were also super excited about what farmers were growing in their fields and the animals that they were raising. It was really an exciting time.”

While Fair Food’s initial goal was to work exclusively with restaurants, the organization soon found a niche in the retail world. After failing to convince Reading Terminal Market vendors to sell local meat, Fair Food launched their own folding table farmstand. “It was a freezer in the back with animal products,” says Karlen. “And it was a table with literature. The produce we put on the table was really more so we would attract people.”

Fair Food didn’t expect consumers to be interested in the produce, but the demand proved high. Soon, the table was open multiple days a week. Eventually they received a small, permanent stand and in 2009, moved to their current location on the west side of the market. Today, the farmstand does close to $1 million in sales annually, selling local meats and produce along with milk, eggs, cheese, honey, flour, breads and much more.

Reintroducing the Farmers Market

By the 1950s and 1960s in Philadelphia, opportunities to buy food from nearby farmers were largely limited to Amish farmstands in the suburbs. “Those always existed, but they didn’t really grow. They were just scattered markets that stuck around, but weren’t contributing to any movement,” says Duane Perry, a former manager of Reading Terminal Market and founder of the Food Trust. By the 1980s and early ’90s, these markets had “dwindled to just a few,” and farmers markets within the city were virtually nonexistent.

By the 1950s and 1960s in Philadelphia, opportunities to buy food from nearby farmers were largely limited to Amish farmstands in the suburbs. “Those always existed, but they didn’t really grow. They were just scattered markets that stuck around, but weren’t contributing to any movement,” says Duane Perry, a former manager of Reading Terminal Market and founder of the Food Trust. By the 1980s and early ’90s, these markets had “dwindled to just a few,” and farmers markets within the city were virtually nonexistent.

During his time at the Reading Terminal, Perry recognized how many neighborhoods lacked access to quality fresh foods. “Through talking to lots of people in the area, as well as in the market,” he says, “we became convinced that one of the things that we could do would be to create more opportunities for food retailing to grow and flourish in some of the Center City neighborhoods.”

Perry launched the Food Trust in 1992 with a vision for accessible, inner-city farmers markets. The first one opened in 1993 in southwest Philadelphia’s Tasker Homes housing development. “Our very first markets were basically one-day-a-week kind of affairs we actually bought food for,” he says, “and brought it and sold it at the markets.” While the response from customers was positive, the market model was problematic.

Around the same time, in 1996, Bob Pierson, a former biochemist turned regional planner, launched one of the region’s first modern farmers markets on South and Passyunk. Pierson, who had taken an interest in local food work after volunteering for his food-buying club in Wisconsin, had moved back to Philadelphia with hopes of creating better sales avenues for local farmers. When a director of community markets position opened at the Food Trust, Pierson applied. In the interview, he pitched a farmer-driven market model. Pierson was hired and he helped establish seven more markets using the new model.

“[These markets] were very, very well-received,” says Perry. “Not only because of their food, but I think that many of the farmers we were working with really had a very strong sense of social responsibility, community spirit and community involvement. They very much wanted to work in communities where folks really need and appreciated their food.”

While Pierson eventually left the Food Trust to found Farm to City in 2000, the Food Trust has continued their farmers market initiative. Now, in its twentieth year, the nonprofit supports nearly 30 farmers markets in the city, including the expansive Headhouse Farmers Market in Old City and Clark Park Farmers Market in West Philadelphia.

In addition to the markets, the Food Trust has also become known for its education initiatives and extensive programming on healthy eating and food access for schools and communities. Their School Market Program provides a hands-on nutrition and entrepreneurial curriculum where students create, own and operate their own food market. And their Healthy Corner Store Initiative is bringing healthy foods into the city’s corner stores to educate about healthy snacking. Their programs have gained national attention as well. In 2007, the Food Trust was named the lead agency for the mid-Atlantic region’s Farm to School Network, and has since expanded the program to reach 25 Philadelphia schools.

Feeding the Consumer Frenzy

During his time at the Food Trust, Pierson had recognized another underdeveloped element of the food movement: the Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. In a CSA, consumers pay farmers at the start of the growing season then receive regular shares of the harvest, typically on a weekly or biweekly schedule. Pierson had set up a CSA in the early 1990s at his workplace, but the program only lasted one year—the farmer decided to return to teaching school. In the years following, Pierson continued to connect CSAs to city customers. “The Trust, that wasn’t on their agenda, I was just doing it,” he says. “But I realized there’s a market for this stuff. So, I left the Food Trust and started Farm to City.”

Initially, Farm to City focused on starting farmers markets and connecting consumers with CSA programs. Halfway through the first farmers market season, Pierson was asked what would happen in the wintertime—customers wanted access to local food year-round. So, the Winter Harvest program was born. The buying club allows area residents to order local food during the winter and spring months.

“I think first-year sales were $15,000, and our peak year was a couple years ago at $300,000,” says Pierson. “[We had a] 50 percent increase on average for about eight years.” Today, the program hosts about 45 suppliers with 500 different items on the list. Products include typical local foods, like vegetables and fruits, plus more nontraditional CSA items, like soap, coffee and canned goods.

In addition to Winter Harvest, Farm to City operates 16 farmers markets and provides online support for buying clubs and CSAs. Through the Farm to City affiliate program, any local food-buying club or CSA can use the website and administrative tools to promote its own programming.

In 2008, Farm to City also helped launch Common Market, which connects local farmers with the wholesale marketplace. Initially, founders Tatiana Garcias-Granados and her husband, Haile Johnston, had wanted to start a farmers market in Strawberry Mansion, but found there was a greater need to bring affordable, local foods to area institutions, like hospitals, schools and universities. Today, Common Market works with more than 100 local farms and 170 institutions, including Jefferson University Hospital, Mariposa Food Co-op and the William Penn Charter School.

Expanding the Reach

While Pierson, Perry, Karlen and Wicks and their respective organizations are different, the goal for each is the same: to bring local, fresh food to Philadelphians.

When Wicks opened the White Dog in 1983, the food movement was in its infancy. “The cheese, oh my God, has changed so much,” she says, laughing. “The farmers and cheese makers are really learning how to make good cheese. Ten years ago, the local cheese was not very good. Now you can do a whole cheese plate with just local.”

Even though Wicks sold the White Dog in 2009, she retains control over its trademark, and won’t license the name without a contract stipulating that local, sustainable and humane food sources are used. And, as the first sustainable restaurant in Philadelphia, it proved a fertile breeding ground for likeminded entrepreneurs. Founders of Philadelphia food establishments Metropolitan Bakery, John and Kira’s Chocolates, the Night Kitchen, Bistro 7 and Picnic all spent time working at the White Dog.

Beyond the restaurant scene, the regular farmers markets, local food events, and growth in urban gardens and farms all point to a future of an expanded local food economy. Mayor Nutter’s 2008 Greenworks Philadelphia has joined the cause, aiming to put 75 percent of Philadelphia’s population within a 10-minute walking distance of fresh food.

“I often say that we have so much to be proud of—Fair Food and all the other awesome groups in Philadelphia and around the country—for creating a kick-ass niche market for family farmers,” says Karlen. “And we’ve really done that through farmers markets and CSAs. The responsibility we have now is to take it beyond just the niche market.”

By then, Green left to have her second child and sous chef Kevin Klause (now of FARMiCiA) had stepped into the executive position. Again, explains Wicks, it was the chef who headed the White Dog’s transition into sustainable food. “Kevin really did all that work,” she says. “I mean, he was the one that really researched where can we get the pork, where can we get the beef, and finding new farms and orchestrating all that.”

By then, Green left to have her second child and sous chef Kevin Klause (now of FARMiCiA) had stepped into the executive position. Again, explains Wicks, it was the chef who headed the White Dog’s transition into sustainable food. “Kevin really did all that work,” she says. “I mean, he was the one that really researched where can we get the pork, where can we get the beef, and finding new farms and orchestrating all that.”

I work with Philadelphia Movers and i've actually seen one of the events from these guys during a move!