Dan Lavin returned from his friend Chuck’s wake feeling troubled. Lavin and his now-deceased husband had met Chuck and his wife in a support group for people with cancer.

“Chuck was a really sharp-witted, spitfire kind of guy,” Lavin says. In the throes of his illness, Chuck bought a Corvette with a license plate that read “NT DED YT.”

Lavin wondered, why was the memorial for someone with so much personality so antiseptic and generic?

He recalled seeing a burial on “Six Feet Under,” an HBO drama about a family-run funeral home, which evoked a very different feeling.

The burial depicted in the scene is simple and intimate. The family lowers the corpse, wrapped in linen, slowly into the ground, and then one by one, family members take shovels and throw dirt on top.

“[The episode] really resonated inside of me,” Lavin says. “I was like, ‘This is the way it’s supposed to be.’”

So he Googled “Nate’s death Six Feet Under” and found out it was a green burial.

An unlikely undertaker

Lavin next discovered the Green Burial Council, a nonprofit whose mission is “to inspire and advocate for environmentally sustainable, natural death care through education and certification.” He then began looking for cemeteries offering green burials. He assumed it was just going to be a West Coast kind of thing, but was surprised to learn that there were many cemeteries like this in the South, and even one nearby: Steelmantown Cemetery in Woodbine, New Jersey.

The owner of Steelmantown and the board president of the Green Burial Council is Ed Bixby, someone who never imagined he would be in the business. “I didn’t choose to be a cemeterian, it chose me,” he says.

Bixby now owns and operates a half dozen cemeteries around the country, but before 2007, he was in real estate and development. His connection to the Cape May County cemetery, however, stretches back centuries.

When his family arrived in the New World in 1680, they were, according to Bixby, given the deed to 195,000 acres of land. What is now Steelmantown Cemetery was a private cemetery for his family. In 1840, his family gave the municipality ownership so it could become a public cemetery. All of his ancestors and family are buried there.

“In death, you should still be able to care for your loved one and in a way that feels like they belong to you.”

— Ed Bixby, owner of Steelmantown Cemetery

In 1957 the municipality sold it to a funeral director who provided a service called “simple burial,” a green burial by another name. The cemetery had a contract with the Woodbine Developmental Center, a nonprofit that supports men with developmental disabilities. Anyone in their care who died would be buried at the cemetery, a simple—and inexpensive—option for the facility.

Eventually that contract ended, and the cemetery fell into neglect. This distressed Bixby’s mother, whose son, Bixby’s brother, was buried there in 1956. So Bixby went to the caretaker, a family friend, who was 87 years old at the time. Bixby asked him to clean it up but the caretaker responded that he didn’t have the money or the means.

He then offered an alternative: “How about if I give you the cemetery?”

He sold the cemetery to Bixby for a dollar.

“This is before I even knew anything about natural burial,” Bixby recalls. His first actions were to have 20 dump trucks of debris removed and to install a mile of hiking trails.

Six months after taking possession of the cemetery, an article in The Press of Atlantic City caught Bixby’s attention. It described what a natural burial is and laid out the criteria for a cemetery to qualify.

Lo and behold, the Steelmantown Cemetery met all of the criteria. Bixby began to consider the possibilities.

What makes a green burial green?

As one might expect, the requirements set up by the Green Burial Council focus on the environment. There is no embalming fluid, which typically contains a mixture of three chemicals toxic to humans: formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde and methanol. There are no vaults of any kind, eliminating the use of cement. Bodies are wrapped in biodegradable shrouds or burial containers. Only stone that is found on the site can be used as a grave marker and granite tombstones are forbidden. Native plants are grown throughout the cemetery.

But perhaps the most crucial component to a green burial is that they must “[p]rovide clients and families with the opportunity to participate in the burial and ritual process.” This, Bixby says, makes all the difference.

Using some vintage wood and antique wagon wheels, Bixby built a wagon so that families can help push their departed loved ones to their gravesite. They can also carry the body to the grave, lower them down and backfill the grave.

Bixby says, “During this entire process [the bereaved are] surrounded by life and the living, the wind blowing through the trees, the birds whistling in the forest. And you can see the grief disappear. … [T]ypically they’re very grief-stricken in the beginning. At the end, when they’re finally done, they look at you and they give you a genuine smile. They say, ‘thank you.’ It’s a surreal experience in the sense that there’s not a tear in the group when the process is over.”

I ask Bixby why he thinks that participation is so critical to the healing process.

“That final act of kindness heals the heart. It’s so cathartic for that family. They don’t have that missing feeling anymore—that the minute their loved one stopped breathing they lost all touch with that person,” he says. “To lay them to rest in that way is life changing.”

In Bixby’s opinion, the modern funeral industry makes people feel a greater sense of despair and loss, and a green burial helps restore a sense of agency.

“If you have a child you care for—you bathe them, you feed them, you clothe them. You do everything you can for them, because you have to,” he explains. “In death, you should still be able to care for your loved one and in a way that feels like they belong to you. You have all full rights to your loved ones.”

When people first come to Steelmantown Cemetery they often believe they can’t handle what’s ahead of them. But Bixby offers strong words of encouragement. “I say, ‘It is in your DNA, believe it or not. It is in you to care for your dead.’ … They come in scared and apprehensive and they leave empowered.”

The hybrid model

While Bixby happened upon a cemetery perfectly suited for green burials, undeveloped tracts of land for new burial grounds can be hard to come by. There are, however, plenty of existing cemeteries that might be able to carve out some land devoted to green burials. This is the hybrid model.

Bala Cynwyd’s storied West Laurel Hill Cemetery fits that bill.

Founded in 1869 by Quaker John Jay Smith, the 187-acre campus is a certified Level II arboretum, and home to more than 3,900 trees, according to Sales, Marketing and Family Services Director Deborah Cassidy. It is the final resting place for a number of famous Philadelphian families, including Rittenhouse, Strawbridge and Widener, as well as nationally-known names like Breyer, Luden, Stetson and Whitman.

Despite its long history, it has not been resting on its laurels, if you will.

“We try to be at the forefront of innovation,” says Cassidy.

West Laurel Hill has a crematorium and a funeral home on site, and began offering services for pet burials using a technique called aquamation in 2018. A much more environmentally friendly alternative to cremation, aquamation involves submerging a body in a solution that is 95% water and 5% alkaline. This speeds along the process of decomposition. After a few hours, only bones remain. These are then ground into dust that the client can keep in an urn or spread as they wish; the nutrients in the water can be used as fertilizer for plants.

Aquamation of human remains is currently legal in 15 states, but not yet in Pennsylvania.

“We are one call to one place for everything when it comes to our death services,” says Cassidy. “We want to make sure that when someone asks, ‘Do you offer this?’ we’re able to do so. And if we can’t at that time, we make sure that we put that in place as one of our strategic plans for the following year.”

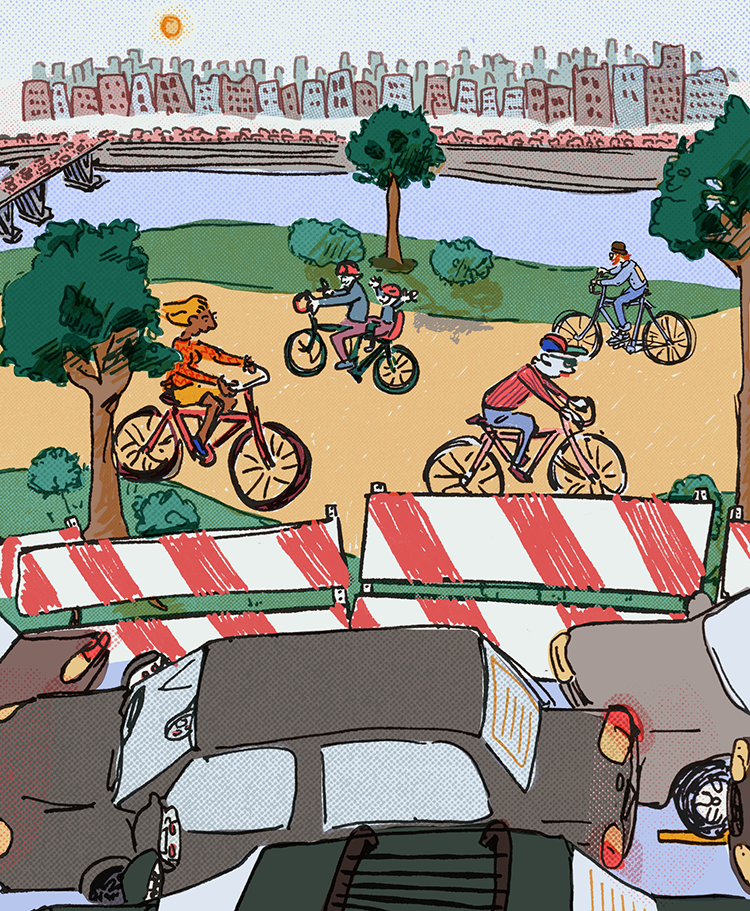

That’s how their green burial offerings emerged. After a few people asked about them, the cemetery launched Nature’s Sanctuary, a natural burial section that overlooks the Cynwyd Heritage Trail, in 2008.

Nature’s Sanctuary has been certified by both the Green Burial Council and the Sustainable SITES Initiative, but it took a significant commitment to get the sanctuary to where it is now.

“I think it was about 2015 or ’16, we decided to take the same property and do a restoration. There were individuals buried in the area and we had sectioned them off, so that we could then take out all of the soil, put it back in, so that we could plant indigenous plants instead of these invasives that were taking over,” Cassidy explains. “Once we did that restoration, people were just very, very interested.”

Also on the sanctuary’s grounds is an apiary. A full-time horticulturist and an arborist are on staff, helping to seed a meadow that will eventually become a woodland.

Demand for the space is strong.

Cassidy says that in 2008, West Laurel Hill had three green burials. Since then, that number has climbed to 96. But the real measure is that the living are making reservations.

“We have over 351 pre-needed properties,” says Cassidy. “So you can see the difference between 2008 and 2020.”

The actual day

It was on Holy Thursday, just a few days before Easter, that Lavin’s husband died. Despite the fact that he had been ill for a long time and that his prognosis was bad, it was still a shock.

“He was planning for my parents to come down on Sunday. In the hospital, he’s telling them, ‘I gotta get out of here.’ And that was the plan,” Lavin says. “I wasn’t thinking about a funeral or anything.”

But then, he had to.

Lavin began to retrace his steps: the “Six Feet Under” episode, the Green Burial Council and then the Steelmantown Cemetery. He began to plan the event after a visit. Originally Lavin envisioned a small service with a handful of people, but when he began receiving emails from his husband’s friends he decided to invite them all. He estimates between 100 and 150 people attended.

Lavin welcomed the guests by explaining where they were and what type of burial they were having. “[N]o matter where we go in our lives, we will always remember this day,” he told them.

The attendants packed into the tiny chapel at Steelmantown. They took turns talking about the deceased, and when one woman spontaneously began singing, everyone joined in.

In this setting, Lavin says, the fear of death seemed to disappear. One friend later told him, “I learned more about life and death at that funeral than I’ve ever experienced.”

Unlike the “Six Feet Under” episode, Lavin chose a biodegradable casket rather than a shroud, because he thought that might be easier for his husband’s parents. He was grateful that he chose the route

he did.

“If you’re embalmed and put into this concrete vault, you’re disrupting the natural cycle of things,” he says. “And I think as humans, we do that so many times. We just disrupt the natural cycle.”

Looking back, Lavin feels that everyone in attendance could see that death itself is natural—not something to fear.

“I think everybody felt safe in the experience of death,” he says.

Processing a loss at a green burial is not scary or cold, he says. “It’s truly a celebration of life.”