Desperate times call for desperate measures—and the times, they are a-desperate.

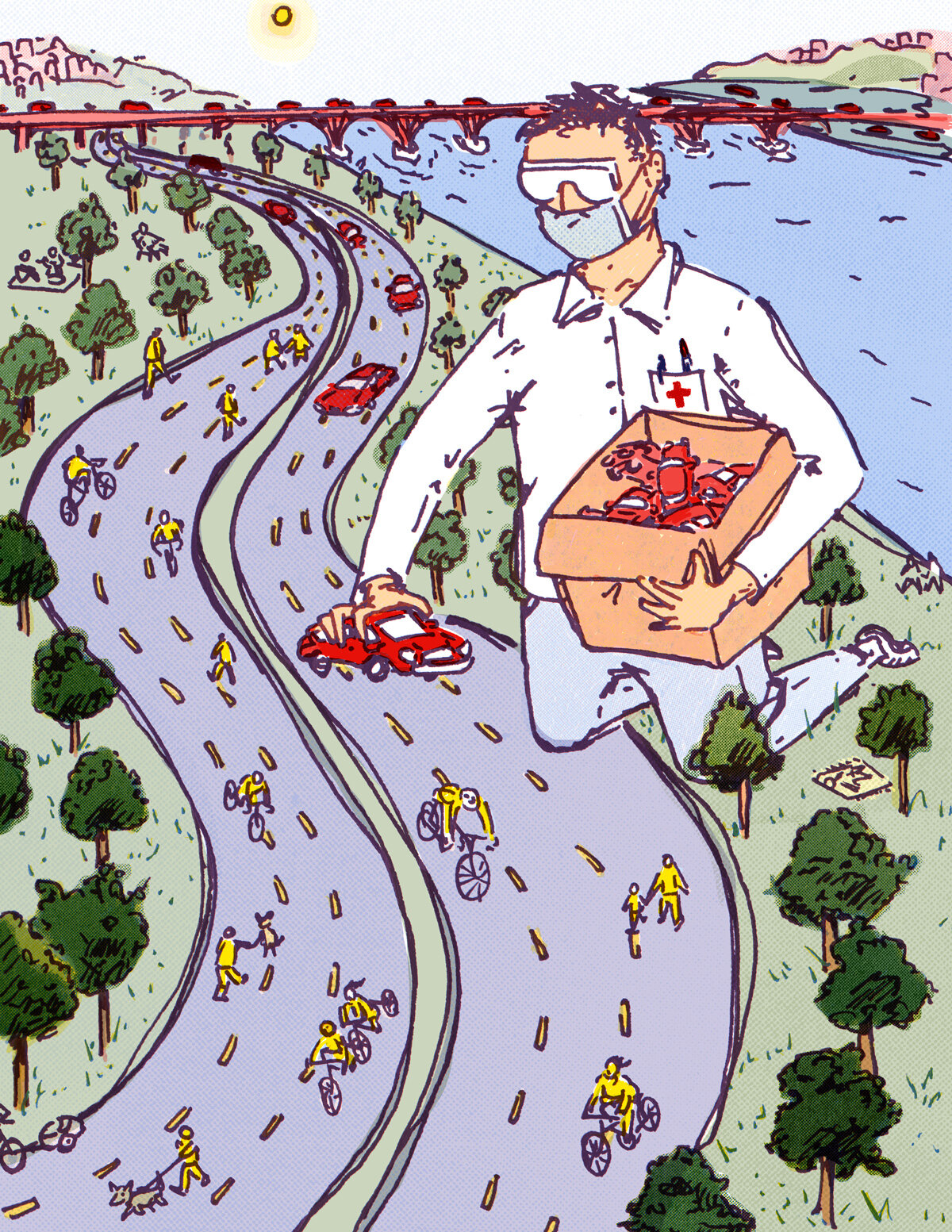

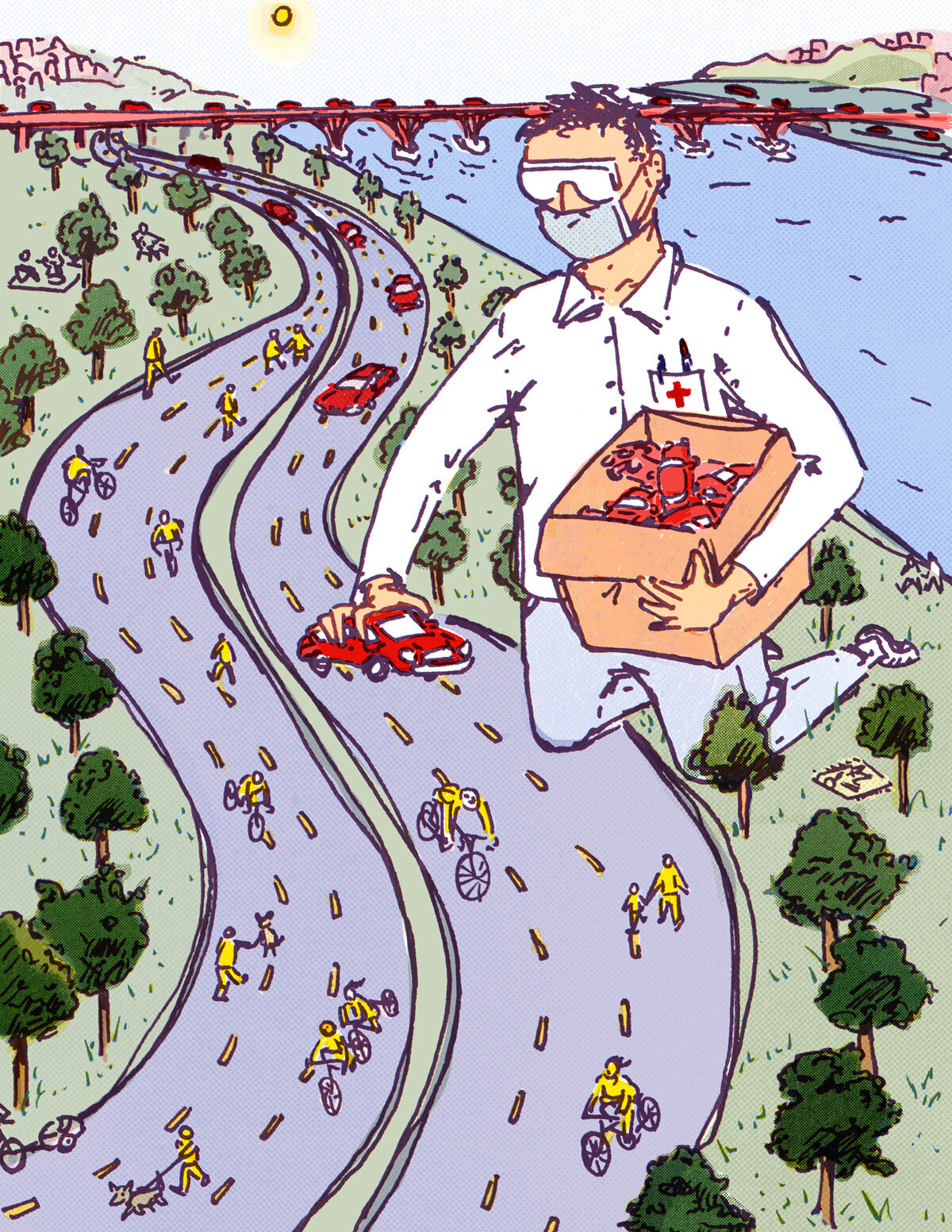

But with a little bit of planning, and a lot of nudging, desperation can bring out the best in people—and cities. Such was the case when Martin Luther King Jr. Drive was closed to motor vehicles and opened to people in late March 2020. It has remained that way since. Such a quick and decisive progressive action—rare for the Kenney Administration—was quickly replicated around the country: Cities and towns began to close their streets to cars and trucks.

MLK Drive was an immediate hit with folks looking for recreation, a safer commute and proper social distancing outside. In late May, volunteers of the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia counted nearly 1,000 users per hour on a Saturday. This is exponentially more than have used the drive for bicycling on a spring weekend in any other year on record, and exceeded the number of people using the Schuylkill River Trail along Kelly Drive.

Bicycle Coalition volunteer counters observed that the users of the drive on evenings and weekends were very diverse, with families accessing the drive by bicycle via the Strawberry Mansion Bridge and Black Road. Folks from all over the city and region have, since then, been driving into the area just to use MLK Drive.

This has been one of the few positive developments to come out of Philadelphia in 2020. Not just because that idea has been replicated or that it’s helped bring out more cyclists to Philadelphia streets than ever before. Among many other changes we’ve seen in Philadelphia and elsewhere, it proves that the red tape we’ve been working around for so long to provide safe, usable streets was never necessary to begin with. Turns out, you can close a street to motorists or remove parking and people with cars will simply find another way to go, or park somewhere else.

Now there’s no going back.

For far too long, the convenience and pampering of motorists has trumped basically everything—the safety of pedestrians and cyclists, the service economy, the efficiency of public transportation.

After MLK Drive was opened to people, a small but still growing group of volunteers and nonprofit organizations banded together to call for expanding the open-streets platform in the city, bringing more neighborhoods and people into the mix and giving more neighborhoods car-free access to their nearest parks. After all, MLK Drive is great, but it can’t be accessed by all Philadelphians, and motorists continue to drive dangerously on less-crowded streets throughout the city.

The proposal was rejected by the Kenney Administration. When asked about the proposal, Philadelphia Managing Director Brian Abernathy noted: “I don’t see what problem we’re trying to solve by closing additional streets.”

That meant no overarching, public plan. The coalition warned that without a plan from the city, we’d see crowded squares, trashed parks and an uptick in traffic deaths.

Our group, now called the Recovery Streets Coalition, consisting of the Bicycle Coalition, Feet First Philly, the Clean Air Council and 5th Square, created an official platform that proposes several easy changes for our streets.

Those changes include the creation of streeteries, moving outdoor dining into parking spaces; protected bike lanes, to help people who’ve taken up biking—and there are a lot of them—do so safely; and Open Streets, to allow for safe social distancing in all neighborhoods. That platform was quickly endorsed by more than 1,000 Philadelphians, several councilmembers, and 19 neighborhood and community organizations and community development corporations.

As of mid-August, the city had not acknowledged the Recovery Streets proposal’s influence on their decision making—but began moving on some of the easy stuff we proposed. Into the summer, the city opened up streeteries for all commercial neighborhoods in the city. As of mid-August, more than 460 businesses took the opportunity to expand their outdoor dining space into the street.

Parklets, which are sidewalk extensions that accommodate sitting, greenery and dining, have historically been sparse. Why? Because the city intentionally made it difficult for a business to get them. Until COVID-19 struck, businesses were required to gather 50 percent near-neighbor approval, a separate insurance policy on the parklet, and architectural drawings approved by the city were required to obtain seating for people that took the space of an empty car.

Neighborhoods around Philadelphia also began closing streets for weekend outdoor activities, and, in places like Manayunk, small side streets were closed semi-permanently for outdoor exercise classes. While it’s not even close to what the Recovery Streets Coalition has called for, and pales in comparison to what our peer cities have done for their residents, it’s a start.

And like the new process for taking the space of an empty car (with a three-day turnaround!), there haven’t been endless community meetings where residents demand to know (sometimes violently) where they will store their vehicles. And, as I’ve written in this column in the past, those arguments often win the day—earlier this year, for instance, a neighborhood group in Northeast Philly successfully blocked a section of the East Coast Greenway (a bicycle trail between Maine and Florida) from being built.

For far too long, the convenience and pampering of motorists has trumped basically everything—the safety of pedestrians and cyclists, the service economy, the efficiency of public transportation. And while there’s a place for motor vehicles in the city, we’ve dedicated two-thirds of most small streets to parking. We have 2,172,896 parking spaces for 1.6 million residents, about 30 percent of whom don’t own a car.

Here’s the thing: We don’t need them.

Not all changes made during the pandemic should remain in place forever. But there are better uses for our streets than empty car storage and waterfront highways—and we’re just beginning to see how true that is.