Author Ashley Gripper (right) with fellow farmers Errol Chichester (left) and Tahirah Chichester (center).

Photograph By Khaliah D. Pitts

The Blacker The Berry

By Ashley Gripper

For more than 150 years, from the rural South to northern cities, Black people have used farming to build self-determined communities and resist oppressive structures that tear them down.

My journey in food-and-land work began long before I was born. My ancestors were enslaved Africans forced to farm under abhorrent conditions in South Carolina, Texas and Georgia. In 2012, I started my first professional job working at a food justice and nutrition education non-profit in Philadelphia, but I first developed a passion for food sovereignty and agriculture at the Black Farmers Conference in 2013.

There, I learned that farming is not new to Black people. While some dominant modern narratives talk about urban agriculture as an innovative way to fight food insecurity, Black folks in this country have been growing food in cities for as long as they have lived in cities. Before that, our ancestors lived in deep relationship with the land. For the first time, I understood growing food as a tool for dismantling systemic oppression. I also realized that Black academics have a critical role to play in agricultural resistance and freedom movements.

As a PhD candidate, I am exploring and understanding the ways that urban agriculture impacts the mental health, spirituality and collective agency of Black communities. Before we even begin to do this type of research, it is important for us to understand the roots of Black farming.

Black farmers across the South created cooperatives largely in response to the anti-Black sentiment of governments and society; in response to supermarkets not serving Black customers; in response to white people terrorizing Black folks when they tried to register to vote. These cooperatives were a means of providing economic autonomy, political education and collective agency to Black people in the South.

Despite migration patterns from the South to the North and Midwest, many Black urban communities have kept in touch with their agricultural roots, establishing farms and gardens throughout the United States. Black people have ancestral ties to this land—to caring for it, nurturing it, loving it and allowing it to heal our communities. We have faced immeasurable discriminatory practices and policies as we have sought to reclaim and live in relationship with the land. We must not forget this history.

Danger lies in the face and narrative of urban agriculture being co-opted by white liberals and academics. It is presented as something new, trendy, and without sociopolitical and historical ties or influences.

This limited perspective views white community gardens and urban farming alone as acts of social justice, which is inadvertently attempts to erase the decades of urban agricultural practices, resistance and activism that Black communities have engaged in. It is why we see white-led urban agriculture projects receiving the majority of grant and institutional funding, further replicating the cycle of narrative dominance, white land ownership and the physical exclusion of Black folks from access to land, wealth and resources.

Resilience in the face of exploitation

In the decades following the Civil War, Black folks sought to acquire land as a means to provide for themselves, their families and communities, and become independent of previous slave and plantation owners. But they faced many obstacles. White landowners and merchants routinely denied Black farmers access to private credit.

They were instead offered exploitative sharecropping or rental agreements. This resulted in many Black farmers being unable to keep up with mortgage and debt payments, often forcing them to sell their land for far less than what it was worth.

Can we pause and talk about resilience? Despite these many concerted efforts to thwart Black farmers, they still acquired more than 16 million acres of land at the height of Black farming in the U.S. in 1920. There were more than 5.1 million Black farmers who made up 14 percent of the overall farming population.

In the proceeding decades, terrorism, Jim Crow laws and increased industrialization in Northern cities drove many Black people from the South to places like Philadelphia; Washington, D.C.; and Detroit. From 1920–1997, the number of Black farmers declined by about 95 percent nationwide.

Today there are about 45,000 Black farmers in the U.S., making up only 1 percent of the farming population, and owning far fewer acres of land compared to 1920. This happened through a series of discriminatory USDA policies and procedures such as heir property, unjustified loan and crop insurance denials, blatant prejudice like forcing Black farmers off their land and terrorism from racist mobs in the South.

Surviving, thriving and self-determination

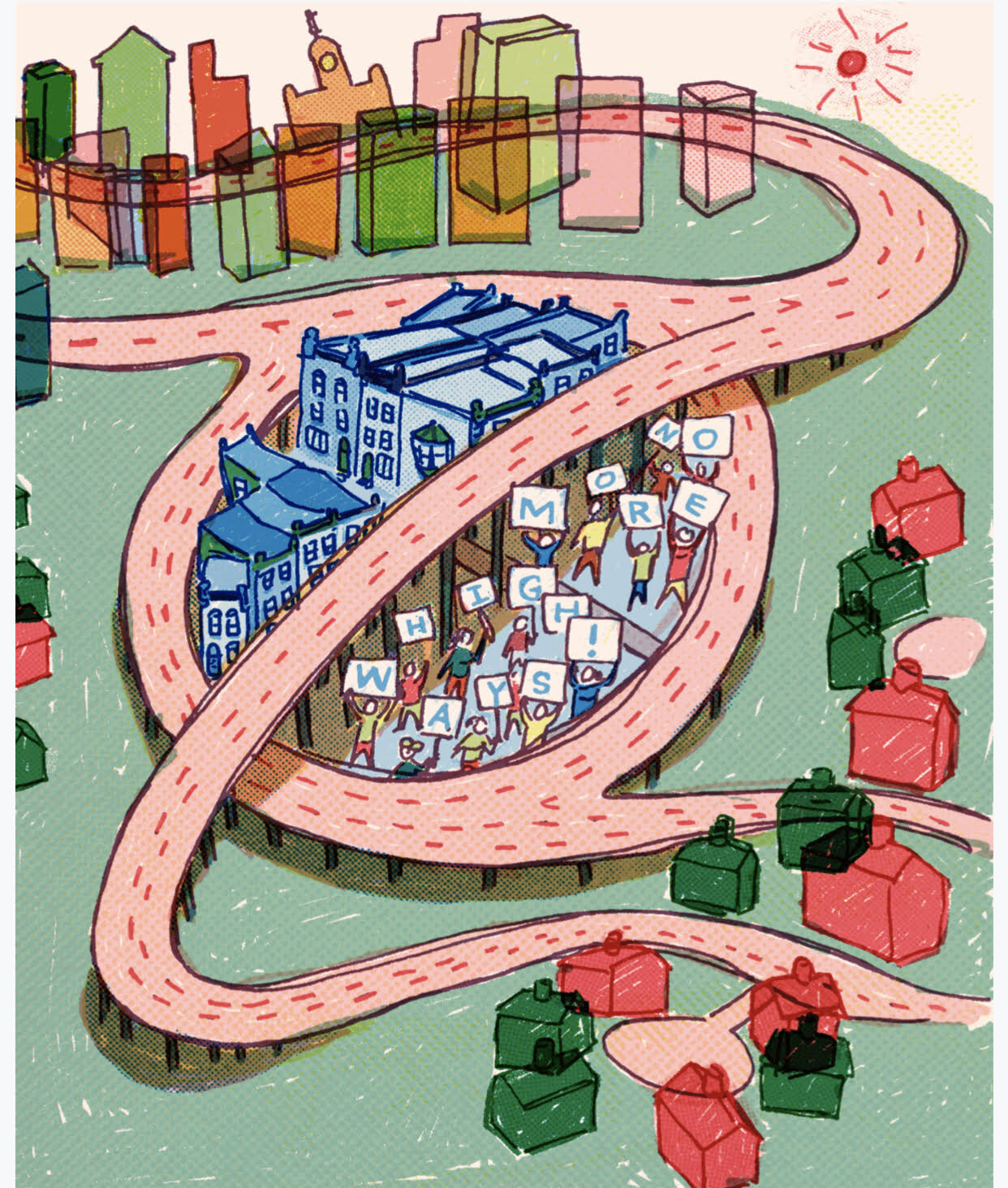

Black farmers and gardeners continue to push for their community’s right to self-determination, to survive and to thrive. Here in Philly, food justice activists and urban growers protest to save their farms and gardens, although City Council control of land sales often make it hard for community members to contend with wealthy developers. These growers and activists understand that, in a city where 81 percent of food stores offer mostly unhealthy food choices, a major key to wellness and collective healing is having control over what goes into our bodies. Data have also shown that those unhealthful food stores are disproportionately located in Black neighborhoods. Unsurprisingly, heart disease is the leading cause of death in Philadelphia.

Heart disease is what the doctors listed on my father’s death certificate in April. They ruled that as the cause of death, despite the neglect, negligence and implicit health-care bias that contributed to his passing.

Diet-related illnesses are often attributed to individual behavior and poor lifestyle choices, but the reality is that these illnesses and deaths are the results of systemic racism.

Black people in Philadelphia disproportionately experience targeted unhealthy food marketing, lack of access to health care and inadequate educational systems—all of which can lead to mental and physical health challenges.

These challenges are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as healthcare practitioners make choices, often rooted in racism, about who lives and who dies, whose life is valuable and whose life can be discarded. The global health crisis highlights that community control of food systems and land are not just important but are quite literally our means of surviving, healing and thriving.

Through grassroots organizing, policy advocacy and urban planning, we are pushing for access to land for emotional, spiritual, physical and collective healing because our communities’ health and livelihoods depend on it.

Gardens and farms provide people with exposure to greenness, opportunities for physical activity and potential benefits to the m

icrobiome, as exposure to soil and its many microorganisms can boost our gut health.

They offer spaces to connect and engage with our neighbors. They provide reclamation and renewal of our spiritual and ancestral relationships to the land. Community-led urban agriculture projects are a means of sharing education and information, strengthening social capital and support.

Agriculture can offer Black people opportunities for economic autonomy while providing safe spaces for community members to gather and celebrate without fear of criminalization or state-sanctioned brutality.

Black agriculture provides a way to engage with the disturbing history of this country, that we live in a place built on stolen Indigenous land and the brutal enslavement and stolen labor of my ancestors. It opens the door to understanding how this all shapes our collective journey toward liberation.

An expanded version of this article was originally published in Environmental Health News. The longer version is available at EHN.org.