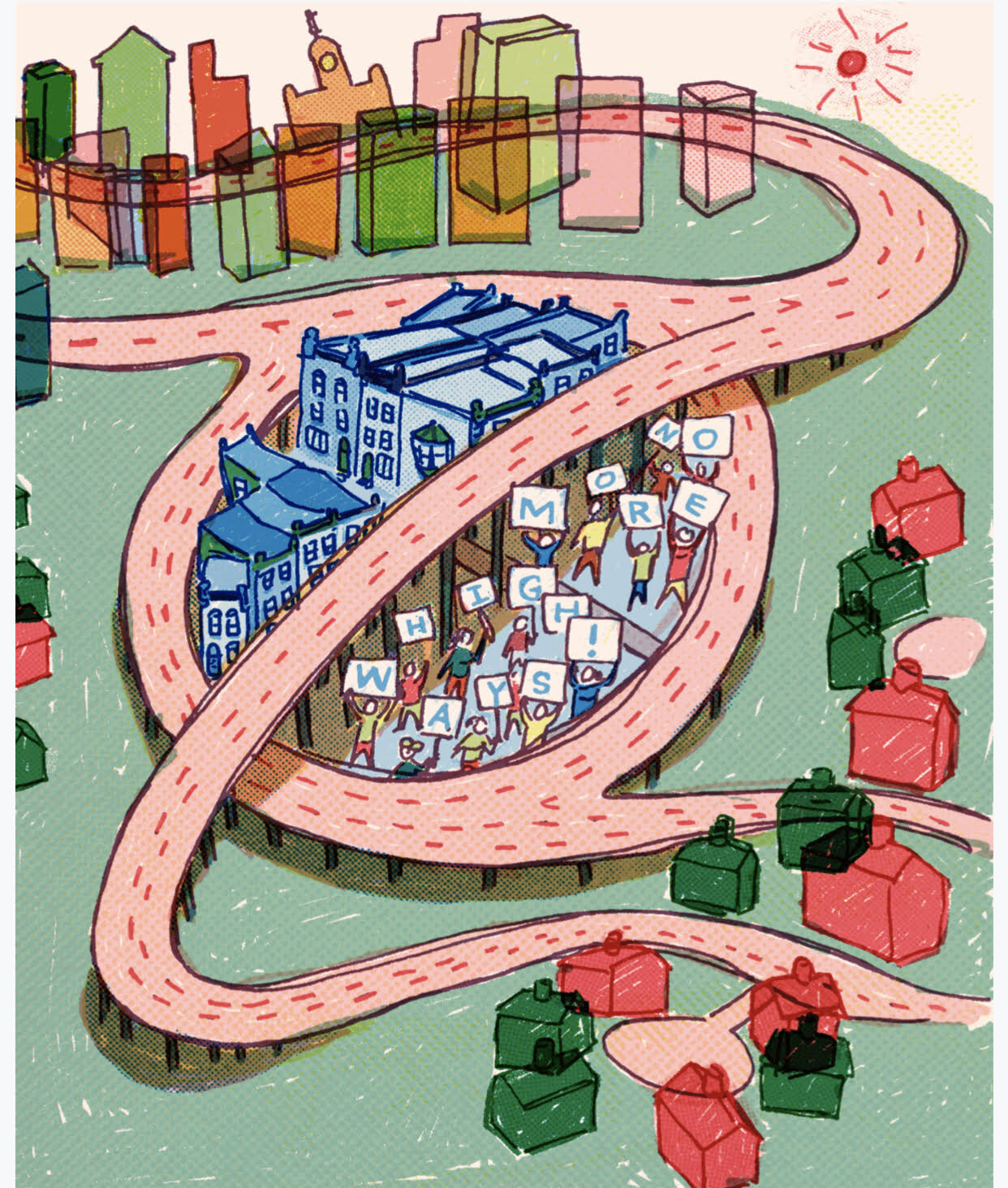

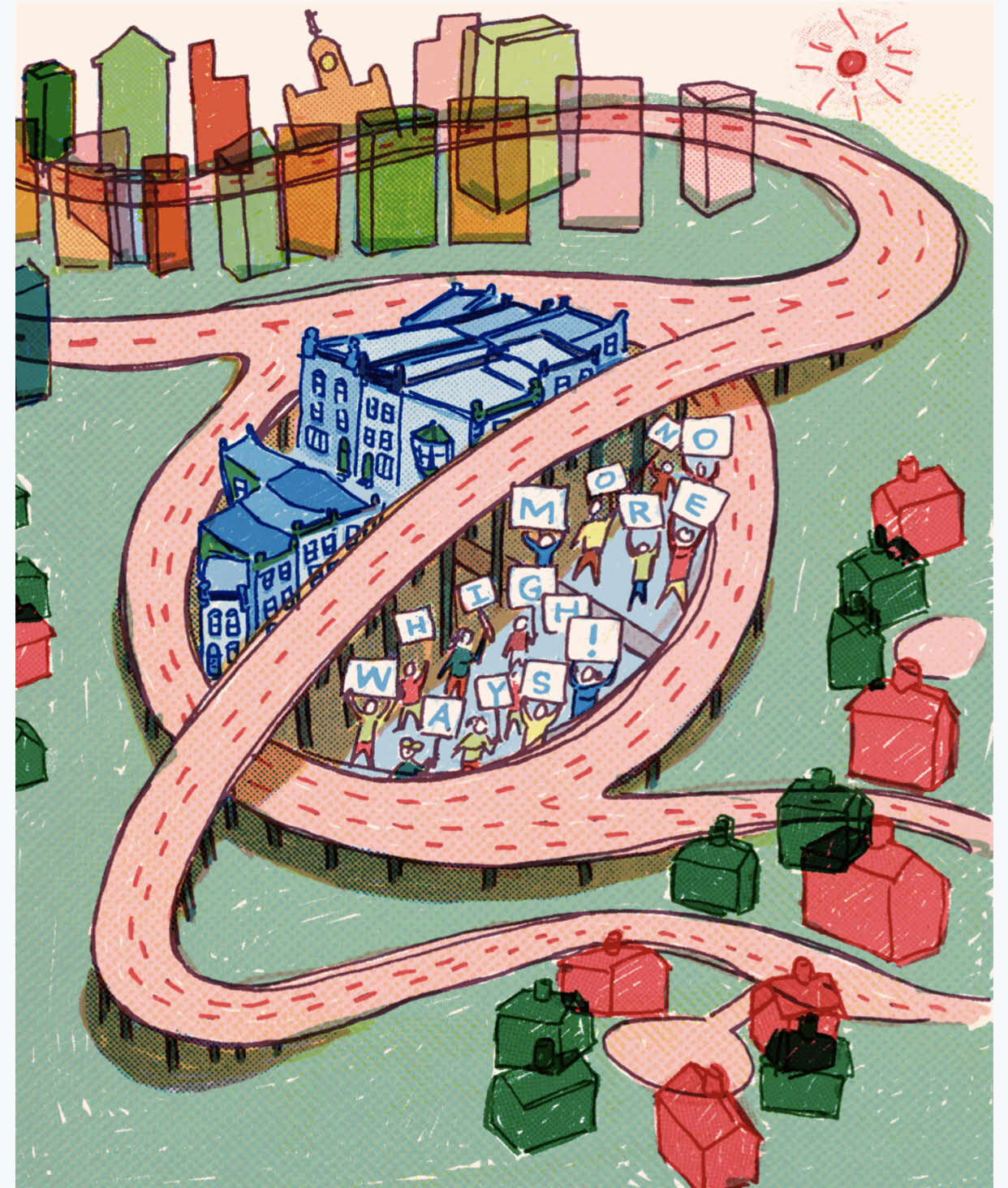

Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

A City Divided

By Randy Lobasso

For many peaceful protesters in Philadelphia, June 2020 started off with a bang. Specifically, the bangs of flash grenades and tear gas canisters exploding below their feet as they attempted to escape from riot gear-clad police officers on Interstate 676. The murder of George Floyd by police had reignited the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, and Philadelphia showed up with large protests, one of which culminated in one of the largest showings of solidarity on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway the city had ever seen.

Over on I-676, though, civil rights protesters had “ignored orders to leave the road,” “began to throw objects” at police, and did not disperse after troopers deployed smoke devices, Pennsylvania State Police spokesperson Ryan Tarkowski told The Philadelphia Inquirer that week.

Soon after, Mayor Jim Kenney and Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw defended the use of tear gas. Outlaw said it was necessary because a crowd of more than 100 people had surrounded a state trooper alone inside a

vehicle and began rocking it, even though there was no evidence of violence on the part of the protesters. An independent investigation of the incident was soon launched by City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart.

Taking over highways during protests is not new. Black Lives Matter rallies have been doing it consistently over the past several years—and not by accident.

Highways are more than just high-speed roads running through the middle of our cities. They have become prevalent staging areas for racial justice protests quite simply because these huge slabs of concrete exemplify the kinds of systemic racism protesters are challenging.

Highways like I-676 are the physical embodiment of middle-management racism that began accelerating during the New Deal era of the 1930s; their presence has continued to cut cities into sections, segregate communities, keep economic opportunities in the hands of the few and create a car-centric sprawl that makes our streets more dangerous.

In mid-20th-century America, state and local officials began pushing the idea that public highways through cities could become revitalization tools for struggling downtowns.

With the automobile age in full swing, car-ownership was rising, white flight to the suburbs was booming and expressways like I-76 and I-676, they said, would reduce commuting costs and improve accessibility, which would, in turn, make downtown inviting to businesses.

Around the same time, massive urban-renewal projects that razed so-called “blighted” neighborhoods were becoming the norm.

Many of these were low-income and Black neighborhoods in which discriminatory housing practices after the Great Depression discouraged investment. Affected communities often protested proposals that demolished or tore through their neighborhoods. In New York City, Jane Jacobs famously led the successful opposition of a highway through Greenwich Village.

In Philadelphia, after seeing how I-676 divided the city in two, community-led opposition was able to stop a project that would have created I-695: An extension of Interstate 95 that would have gone through South Philadelphia, West Philadelphia and Southwest Philadelphia. Construction on I-695 was projected to begin in 1964, the same year I-676 was completed. The funds that would have been used on that highway project eventually went toward public transportation.

But in many cities, protests couldn’t stop these projects. In fact, according to a paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, economists Jeffrey Brinkman and Jeffrey Lin found that most urban freeway projects were built according to plan, despite opposition.

“In most cities, highways came anyway,” Linda Poon wrote in CityLab in 2019. “And when they did, they disproportionately affected those living in communities of color and neighborhoods with lower education attainment: By the mid-1960s, white neighborhoods with more affluent, better-educated residents had more success putting new policies to use and keeping highways at bay.”

While neither Mayor Kenney nor Governor Tom Wolf mentioned the significance of protests on a highway during the immediate upheaval (they were meeting in City Hall during the chemical attack), Minnesota Governor Tim Walz spoke about it after protesters took over I-94 between St. Paul and Minneapolis that same week.

“It wasn’t just physical—it ripped a culture, it ripped who we were. It was an indiscriminate act that said ‘this community doesn’t matter, it’s invisible,’” Walz said of the highway. “This convenient place to put a highway so we can cross over … and go from the city out to the suburbs.”

Today, we are still feeling the effects of highway planning on our neighborhoods. It is generally harder to develop housing near Philadelphia’s highways, and the noise and pollution make the space alongside I-95 and I-676 less than desirable.

Of course, highways aren’t the only factor that led to increased segregation, income inequality and unfair policing practices in major cities like Philadelphia. Red-lining practices prefaced urban highway expansion and renewal, and banks were essentially barred from lending money to people in neighborhoods across major cities if they happened to live in a red-lined area.

But highways, and even pseudo-highways like Roosevelt Boulevard and Lincoln Drive, continue to divide communities; their poor planning has led to regular injurious and deadly crashes that we all pay for. And while the urban highway revolts of the ’50s and ’60s led to more community input on major projects, the damage has been done—and it’s something we might not be talking about without the heroic people protesting and speaking out on these highways that were once contested themselves.