Illustration by Carter Mulcahey

The Eagle Has Landed

interview by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

If you’ve just arrived in Philadelphia, you might not know that along our famed Boathouse Row, athletes were once advised to have tetanus shots to safely compete. Industrial waste and municipal sewage sullied our waters, and you were more likely to see floating garbage than turtles or fish. Now, after decades of public and private investment, the William Penn Foundation’s watershed expert Andy Johnson says wildlife has returned—and Philadelphians of all backgrounds are starting a love affair with our revitalized rivers.

We can’t get by without water, and the health of our rivers and water supply is about human health, ecological health and economic development. How has the health of our rivers improved biodiversity?

AJ: I was out with a group yesterday on the Cooper River in Camden—UrbanPromise, who build wooden boats. We fund them and they have programs for the youth who are involved in building the boats to actually put them on the water and take residents of the community out and give them guided tours.

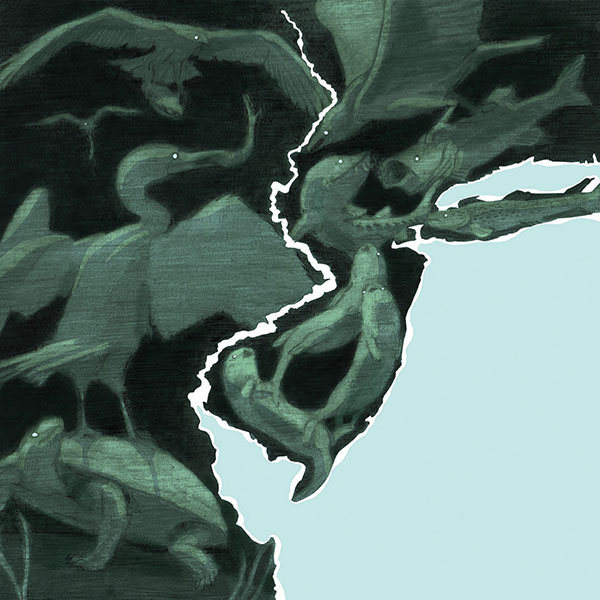

I know that until the 1980s there was primary sewage being discharged into that river, and there were virtually no birds and virtually no fish, and it smelled. Yesterday, we saw two bald eagles, an osprey, many cormorants, fish jumping, and it was a wonderful experience.

I think that’s emblematic, and we see that on the Schuylkill, other rivers and on the Delaware itself—where there’s evidence that fish have come back and birds have followed—and aquatic vegetation. There’s celery grass that’s growing on the Delaware between Camden and Philadelphia on the shores… It’s very sensitive to pollution; it’s an indicator species. The fact that it’s growing means the conditions are sufficient.

What was the original cause of the deadening of the Delaware River?

AJ: It was primarily from industrial waste and municipal sewage. Of course, agricultural runoff was there, too, and there are other things, but those were the primary causes. [This] may be apocryphal, but supposedly as airplanes approached Philadelphia and came in over the river, the pilots could smell the river. Whether or not that’s true, it’s sort of a compelling image. So,

Philadelphia had this big turnaround because of the Clean Water Act. I don’t think there’s any question that state and federal regulation that addressed water quality had a huge effect.

In what other ways are people interacting with our waterways now that they aren’t as foul as they used to be?

AJ: One example is rowing on the Schuylkill, which of course persisted through the heavy pollution, but in the past it was highly recommended—or required—that rowers have tetanus shots. I don’t think that’s the case anymore, and there are now triathlons that have a swimming element in the river. There are dragon boats, outrigger canoes, kayaks, standard canoes… I think that’s testament to the quality of the water.

How do you feel Philadelphia compares to other cities that have proximity to waterways?

AJ: My sense is that we have the bones and the history, the traditions, to have significant growth in on-water recreational activity for everyone in the community—not just elite people who can access yachts.

I think that one of the continuing challenges is public access to those waterways. There are two different kinds of access: One is being able to see the water, which is important because then you get a feel for it, and the other is actually being able to get to it.

Does the city’s master plan address that?

AJ: I think that the master plan includes the right of way along the river and the idea of a trail, which is one of our strategies—in Philadelphia and beyond—the regional trail network that will have miles and miles of trail along waterways. And that’s a way that people experience the river without having to be on [it].

And then the key is to connect to some access point. So, Independence Seaport Museum, for example, now has programs in part fed by Spruce Street Harbor Park, where there’s all that activity. It’s not people going expecting to shop in a shopping mall—that was sort of the vision before: that you go to a shopping mall on the river. Last summer, the numbers at the Independence Seaport Museum went up by 20,000 people, and that’s largely because they’re more visible.

It seems as though it is requiring significant human intervention to just get back to the way that the normal system would be functioning.

AJ: Nature is resilient, so you don’t necessarily have to restore things to pristine conditions, but there are certain factors that can be addressed. Floodplains, for example—there can be deliberate efforts to restore floodplains, which are so important in terms of ensuring percolation and then preventing erosion and sediment going into water.

And to protect us from some of the catastrophic consequences of storms and

flooding.

AJ: Yeah, it’s a little bit counterintuitive, because what many people have noticed is that after major weather-related disasters, the impulse to repair and put things back—often some of it’s counterproductive in the sense that there’s rebuilding that’s exactly what was there before, recently, that was destroyed. And then others is removing elements of the landscape or the floodplain or the corridor that actually help to slow floods down. What happens is there’s emergency funding after a disaster, and then the wrong kinds of projects are implemented.

Is there enough urgency around the region to address the threat of superstorms?

AJ: I think that there is probably not enough urgency nationally around those issues. And it’s a really volatile set of issues—it’s not inexpensive and it sort of disrupts the status quo, but it is necessary to think about the consequences and preventative steps that can be taken.

Clearly having beautiful waterways and people seeing them coming into the city from all directions matters—it makes a difference to how we show as a city. How does the health of and access to our waterways affect economic development?

AJ: It’s pretty clear that everything that’s happening along the Delaware… the fact that the river doesn’t smell, and that it’s clean and it’s pretty—meaning it’s not filled with trash, it looks bluish instead of always looking brown or green—that’s something that I think is represented in renderings for these great plans for redevelopment on the land.

You see this beautiful river in the background, but there’s almost no discussion in that context of the river.

[We need to be sure the river] is always part of the discussion when there’s a presentation about a big redevelopment project: “By the way, because the river’s clean, that’s why we’re doing it here.”

And I think that we have an opportunity to have some additional public access in Philadelphia to the Delaware. The Schuylkill has great public access—but the Delaware is so cut off from the city. [It’s] an opportunity: Spruce Street Harbor is an example… the North Delaware on Lardner’s Point, some other parks that are being developed… those kinds of examples, I think, are just essential.

I was recently at the FringeArts building at Race Street—the river is in the background, and it’s lovely to see. But there’s so much more pedestrian traffic alongside what is a very busy highway. I saw people crossing in the middle of the highway. The city will need to address that

in some way.

AJ: It forces other decisions and other questions—and that’s definitely one of them—and other kinds of safety, too. You don’t want people just getting onto the river willy nilly—it’s a serious river. But then I think Independence Seaport Museum is planning to expand the public dockage that they have. They already have really cool opportunities for different age groups to get on the water.

Glen Foerd, which is owned by the city, is planning to put in docks and have more access to the water there, and that’s connected to the East Coast Greenway trail, and that’s sort of emblematic of this goal of having the trail network that’s near rivers, that then connects to public access points to the river.

As a Philadelphian, how did it feel to see those kids on the river?

AJ: It’s thrilling. I was proud of people I didn’t know. They were so enthusiastic, and they were so excited, pleased and also wondrous. To see a bald eagle? Even though they’d seen a bald eagle before, which is incredible when you think about that. It’s not that unusual for them! But it’s something that’s really moving. That’s the diversity. That’s the value in making sure that this kind of thing isn’t seen as a white, elite, “it only matters to the suburbs” kind of movement. It matters to people everywhere. … It’s fragile. We can’t take it for granted.

Andy Johnson is a program director with the William Penn Foundation in Philadelphia.

I live along Newton Lake Creek and the amazing amounts of wild life in and around the water is truly a blessing to view and photograph.

Water is a major source of living energy it well being is as important as everything else.

Thank you for this interview! Great information !